All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

It was a dislocated unfriendly old house with Victorian additions and plenty of empty rooms. There was a constant smell of meat cooking. On any day you could open the Aga and there was always one in there, meat was continual, and when it wasnt a joint it might be a tongue or a gut. Plus, there was the enormous ancillary vessel of dog meat, stewing without specification, and cooling through long winter afternoons into ultimate paralysis under two inches of yellow fat.

The history of its meat clung about this house like a climate. Like oil-vapour in a garage. Perhaps the only room immune was an upstairs back bathroom, facing north. Someone once said, Lets stop this bathroom being green? But they ran out of interest, it was green and old yellow. In here were the six toothbrushes of the residents and an egg-coloured carpet with a known verruca. But there was hygiene in here. A smell of cloths provided antidote to the dinners and hours abandoned to them in this apartment of ruined tiles.

It was in this area that his grandfather liked to lurk about, not necessarily in the bathroom, not necessarily excluding it. He rode the toilet like a horse, facing the wall, and crept around in the attic with his penis out. The boy knew this because he was always creeping around too. Sometimes they inadvertently spied on each other. On one occasion he was concealed behind a bedroom door, staring up the hall, and he saw an eye behind the crack in another door, staring back at him. The boy and his grandfather shared more than they might have imagined. Both liked secrets and were interested in the secrets of others. Both thought a lot about nudes.

His grandfather carried pictures of nude women and quite often sent away for brassiere catalogues. Anyone prepared to scale a fifteen-foot wall could lie on the roof and watch him in his office. Inside were a pair of wooden filing cabinets, a desk with an ancient Olivetti, and two twelve-volt lead-zinc batteries wired into a Morse key. Unfortunately, the only way to observe him in here was by hanging over the gutter and cautiously lowering your head. This meant everything was upside-down, but it was the only way to watch him with his sleeves rolled up and a cigar in his mouth, working on his nudes with a razorblade and pot of gum arabic.

Walter was extremely old and full of cancer, although they hadnt diagnosed it yet. On the day the first cell divided the boy got his first pubic hair. The hair was unimpressive and the cancer just a few miscreant spores in the old mans gut. No one knew anything about either. Except Walter had lost weight. He was two holes up on his watch-strap and his coat hung off him like a coat on the back of a chair.

On summer evenings yellow light bored into the cigar smoke and the part of his head that was chromium-plated shone. Sometimes you could see your face in it, like a hubcap.

What are you looking at?

Nothing.

He was careful how he combed his hair, manipulating specially grown long bits over the top and securing them with a wad of grease. This wasnt always successful. During sultry weather his plate warmed up, melting the Brylcreem, and his dome would emerge like part of a small bollard. I have to tell you when you were looking at this you were looking at something. Thats why he wore a hat.

What are you looking at?

Nothing.

Youre a liar.

He was right. The boy was a liar. They were both expert liars. In 1914 his grandfather had lied to get into the army. He signed up, lying about his age, and they rigged him out in big boots and gave him a ride to France. He was the best Morse-code operator on the line, he could think in fucking Morse. He didnt know it then, but Morse was the only thing he was ever going to be any good at.

They took them by train to a little town in Belgium a few miles behind the fighting. The Germans had been here for a year or more and junked the place up somewhat. Even the school was full of bullet holes. Did they shoot the children? Who knows, there are no children here to tell. They got billeted in some of the downstairs classrooms and for a month or two this is where the Morse came in. Fifteen words a minute if you were good. Walter could send thirty. He could look across the dead-zone towards the collapsed church where they blew up their own God and hear it in a series of electrical discharges dit dit dah dah dit hits in his head like organised flies. But what about the pretty evenings when the weather was pink? What about the girl he fucked in the meadow? Can Morse ever be beautiful? I cant think so. Surely this kind of language is only good for ugly things, like horse blood, and maggots in the horses head? Kissing tits sounds just about the same as your arse blown off.

..................

....................

Rain all over the town and it felt like the 35th of January. Thats what he wrote home to his sweetheart, Ethel, although he didnt write that much. Then the message came, and he was the first to transcribe it: Were out of here, and going on some kind of offensive in a place called Passchendaele. The officer was a new boy, never heard of it, and looked it up on a map. As it turned out it wasnt too far away.

Walter had never seen a tank before and laughed when he did. It was like an elephant in an idiots dream. Diesel pouring out of its head, like an elephant breathing like a whale.

But it was big and made him feel so little and realise he was still a boy.

Thats why he laughed.

At twenty minutes past two that afternoon half a kilo of shrapnel took the top of his head off like it was opening it for breakfast. Another element of the same shell hit him in the gut.

He heard it in Morse.

........

Im dead.

Twenty thousand went into the toilet that day but Walter wasnt one of them. For seventeen days he lay where he fell, buried under a heap of horses and rotten Scottish dead. When the Germans picked him up his eyes opened and they stuffed his brain back in as an experiment.

He lived.

It was a story his grandson liked to hear. He liked hearing about the Germans and magic flies. The hospital in Koblenz was full of both and Walter genuinely never knew which one of them saved him.

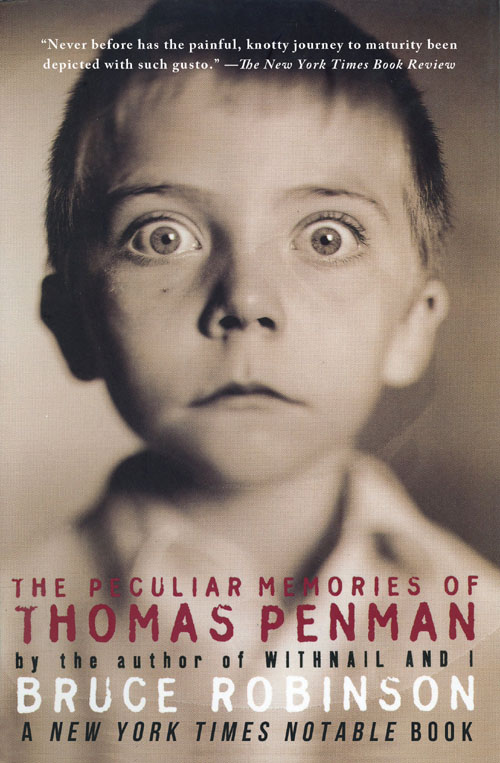

His grandsons name was Thomas Christopher Penman, a thirteen-year-old asthmatic short-arse with big ears and an unwholesome characteristic. If you want the picture in more detail, from the age of four he navigated all lavatories and shat himself everywhere else. This was nothing medicinal, there was nothing wrong with him, he wasnt incontinent or anything like that. No, he shat himself because he wanted to, it was wilful, and not a room in the house nor its considerable gardens was beyond his remit. Sometimes they saw him in his workshop, sometimes in the Wolsey, or cross-eyed and ecstatic in the raspberry canes. More often than not he located on the landing, wedged between the wall and piece of furniture called a tallboy. When there was no one around this was his favourite spot. It was a dark, secret place, with bland wallpaper covered in dots. No one else ever got in here. (The only other person who ever got in here was his grandfather who had been known to exploit the isolation to hang his testicles over the banisters.)