Depiction of the zodiac from a manuscript on automata and water clocks by al-Jaziri, 14th century.

About the Author

Chase F. Robinson was Lecturer and Professor of Islamic History in the Faculty of Oriental Studies and Fellow of Wolfson College at the University of Oxford from 1993 until 2008, when he was appointed Distinguished Professor of History and Provost of the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, where he now serves as President. His extensive publications on Islamic history include Empire and Elites after the Muslim Conquest, Islamic Historiography, and The New Cambridge History of Islam, Volume 1.

Contents

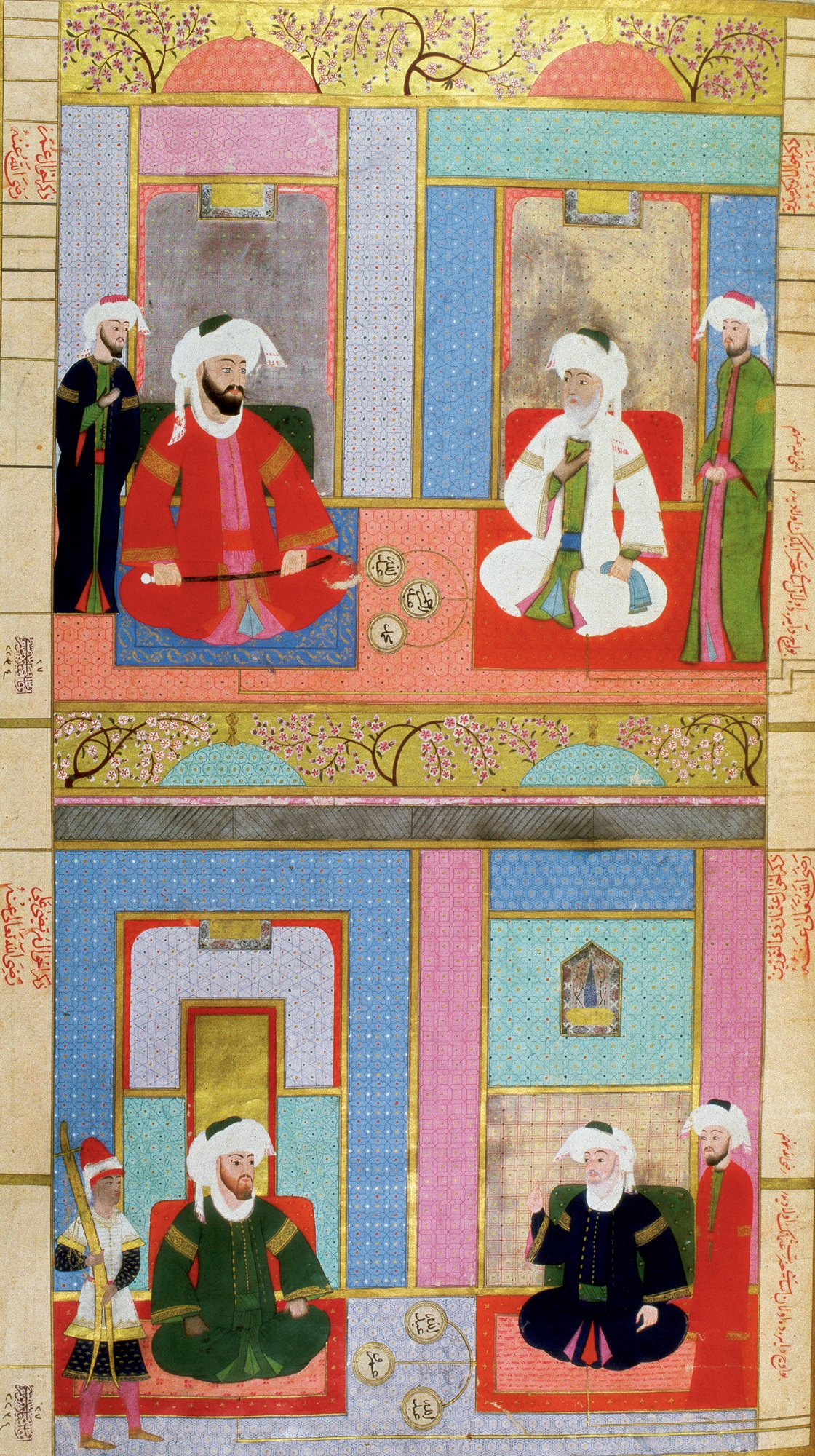

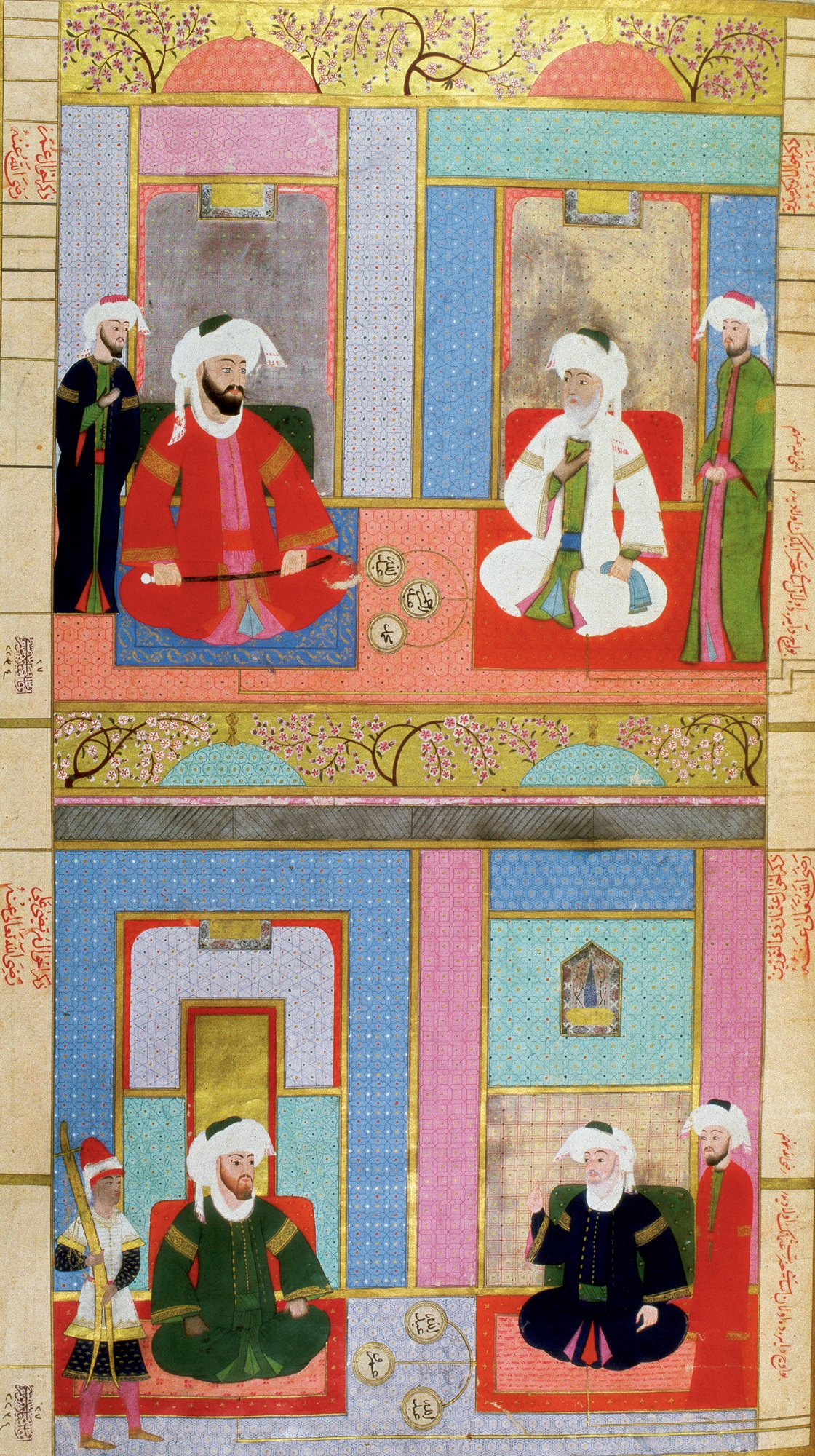

A 16th-century Ottoman miniature showing the first four caliphs who ruled after the death of Muhammad.

Are the Saracens the Ottomans?

No, the Saracens are the Moors.

The Ottomans are the Turks.

So reads, in its entirety, Lydia Daviss micro-story Learning Medieval History. In conventional (and now obsolete) usage, the Saracens are Moors, and the Ottomans, Turks. But learning history is more than assigning labels, as Daviss satire tells us. At least to my mind, history is an exercise in critical imagination, and in the case of the Middle East, this exercise has become all the more important.

This is because the Islamic past has never mattered more than now, what with civil war fracturing societies along Sunni and Shiite lines, militants reviving traditions of jihad and donning the mantle of caliphs, and those in and out of power making various and often wild claims about what constitutes true Islam. Anyone attentive to events in the contemporary Middle East is likely to intuit that history both real and imaginary has an enduring and (perhaps) undue influence upon the politics and culture of the region; misunderstandings of that history also condition Western perceptions of Islam and Muslims. The present is not merely shaped by the past: it is constituted of conflicting claims about the past. As Salman Rushdie put it, we are all irradiated by it.

How is one to judge the claims made about the Islamic past? More specifically, how is one to distinguish between fantasy and myth on the one hand, and genuine history (at least as reconstructed according to modern standards of critical scholarship) on the other? My hope in writing this book is to make available scholarship that is typically specialized and inaccessible, and thereby to offer some answers. According to an oft-transmitted Prophetic tradition, When God wishes good for someone, He gives him understanding in religion. In what follows I hope to address some of the misunderstandings and myths that attach to Daviss schoolboy categories.

For reading and improving parts or all of this book, I am grateful to Anna Akasoy, Jere Bacharach, Paul Cobb, Matthew Gordon, David Morgan and John Robinson. Ian VanderMeulen did some invaluable spadework early on. At Thames & Hudson, I am indebted to Colin Ridler, who launched the balky ship to sea, and to Jen Moore, who steered it safely into port. Julia MacKenzie improved the text in innumerable ways, and Sally Nicholls did exemplary work in picture research. Finally, two anonymous readers offered useful comments, and one of them spotted a few howlers. I thank them.

I dedicate the book to my own Young Turk.

Academic writing on Islam and Islamic history typically follows linguistic and dating conventions that are opaque to the non-specialist. For example, the name of the renowned intellectual al-Ghazali, whom we shall meet below, is usually rendered as al-Ghazl, and his lifetime computed as 450505 AH/10581111 AD. The transliterated letters indicate long vowels in the original Arabic spelling. (Persian and Turkish, the two other languages relevant here, have modified transliteration systems of their own.) And AH is an abbreviation of anno hegirae, the year of the Hijra, the Latin convention compounding the obscurity of an Arabo-Islamic lunar calendar that differs from the solar model most readers of this book take for granted. For the sake of clarity and brevity and perhaps even as an act of mercy I shall dispense with these and many other scholarly conventions.

But I shall not abandon them altogether. Some would simplify Ibn Sad to Ibn Sad, and isha to Ayesha. That would be going too far, in my view, so in what follows one will find Ibn Sad and Aisha. Some readers like to know the sounds of the letters they are reading, such as kh (the ch of loch or chutzpah), gh (akin to a gargling), (produced by a constriction in the throat) and (a glottal stop, like the Cockney bouhl for bottle). In the case of figures for whom Anglicized or Latinized versions exist, such as Mohammed and Algazel, I have usually adopted simplified forms of the Arabic: thus Muhammad and al-Ghazali. Similarly, I shall use Quran instead of Koran. When it comes to non-Arabic names, I shall simplify as well: purists would transliterate the name of the Ilkhanid ruler who reigned from 1304 to 1316 as ljeit, but I shall stick to Uljeitu. It may be some consolation to the purists that I am doing my part to move the world from Genghis Khan to Chinggis Khan.

There are other complications and compromises. Muslim names in this period typically encode genealogical relationships, such as son of (ibn, often abbreviated as b.) and father of (abu). In some cases, such as Ibn al-Muqaffa, literally Son of al-Muqaffa , they have become integral to the name. In fact, names are frequently problematic: we shall see that Ali was the son of someone named Abu Talib, and the father of a son named al-Hasan; it follows that hes known as Ali, son (b.) of Abu Talib and Ali, father (Abu) of al-Hasan. (Hes also called Father of Dust, and no one knows why.) Muslims naturally used their own geographical terms, but for the most part I shall use modern equivalents. Readers do need to be aware that the nomenclature of modern nation states can mislead: the Arab Republic of Syria covers but a part of historical Syria, which also encompassed areas now belonging to Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey.

As will become clear, much remains unknown about many of the figures featuring here. For example, childhoods are usually lost to history, and as much as it is the rule that death dates are fairly accurate, birth dates are very rarely so. For most famous people were not born famous; and unless their families or at least their fathers were notable in one way or another, birth dates were usually forgotten. Rumi (d. 1273), whose father was a well-known scholar and mystic, is the exception that proves the rule. Sometimes silence was even filled with legend. We can be fairly certain that Timur died on 17 or 18 February in 1405, but we shall see that his birth date was concocted. I shall therefore dispense with birth dates.

The problems do not end with dates, however. The evidence for these biographies mainly historical, biographical and literary accounts is often as misleading as it is exiguous. Because memory and record were often compounded over centuries by legend, myth and misunderstanding, we generally know much more about the afterlives of early Muslims than we do their actual lives. We shall see that Rabia al-Adawiyya was an eighth-century ascetic, but the compound portrait constituting her afterlife belongs mainly to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The later the figure, the fuller and more accurate the historical record tends to be, but even then, fame and infamy meant distortion, as it does now.

Next page