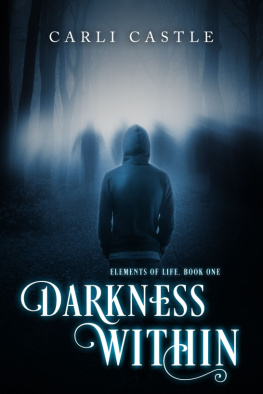

Copyright 2019 by Steve Rushin

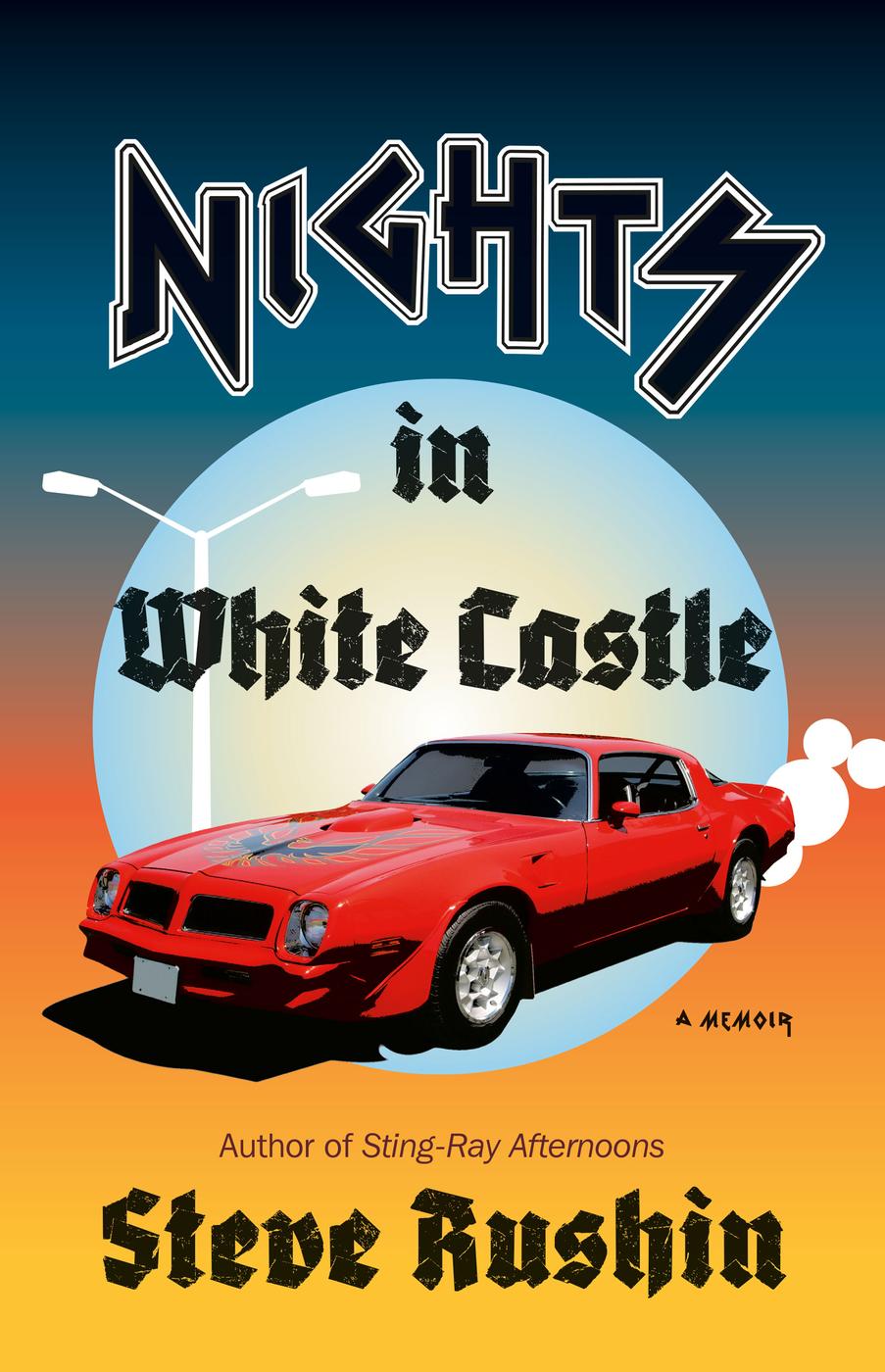

Cover design by Julianna Lee

Cover art: iStock Images (car); Shutterstock (remaining images)

Author photograph by Rebecca Lobo

Cover copyright 2019 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrown.com

twitter.com/LittleBrown

facebook.com/LittleBrownandCompany

First ebook edition: August 2019

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

All photographs are from the collection of the author, unless otherwise noted.

ISBN 978-0-316-41944-4

E3-20190717-NF-DA-ORI

For Mike and Keith

and

my lupine saviors:

Alex Wolff

Jane Bachman Wulf

Rebecca Lobo

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

O n a bright spring day in his senior year of high school, my brother Jim and his buddy Fluff persuaded the manager of our local White Castle to lend them two steel-blue smocks and paper hats of the kind worn by Whiteys kitchen personnel everywhere. Jim put on matching pants, and Dads white belt and loafers, and arrived that evening in period resplendence at Shultzys house for the costume party that would live in lore among the Lincoln Class of 1979.

They left the party early, at eleven oclock. Their night endedas nights often did in Bloomington, Minnesotaat White Castle on Lyndale Avenue, where Jim and Fluff introduced themselves to the night manager as his newest employees, hired that very afternoon. They were assigned to the stainless-steel steam grill where the restaurants famous five-holed hamburgers were loaded onto square buns. It didnt bother anyone, Jim would say later, that we were completely hammered.

Thirty minutes after Jim and Fluff punched in, Shultzy and the rest of the party turned up at the Castle, a hundred Lincoln Bears ravenous for gut bombs and roach burgers. White Castle hamburgers are known by two dozen other pejoratives, but my brother refused to serve anyone who used them. He insisted on decorum and brandished a stainless-steel burger-flipping implement at any patron wholiterally or metaphoricallystepped out of line.

As that line grew, Jim frantically filled paper sacks with cheeseburgers and fries and handed them over the counter to his friends and classmates, bypassing the White Castle cashiers. When the night manager realized what he was witnessinga meticulously planned hamburger heist, an inside jobhe shouted at Barney, the Castle rent-a-cop, to chase Jim, Fluff, Shultzy, and the rest of the Lincoln seniors off the premises.

At the time, Charley Pride had a hit on the radio that went, Burgers and fries and cherry pies, it was simple and good back then. And while Pride was singing of a vanished 1950s drive-in culture, our White Castle remainedas the 1970s turned into the 80sa backdrop for our burgeoning dreams.

White Castle was a halfway house for adolescents as they moved from child to teen to young adult, in that brief period when life resembles a classroom evolution poster: the child rising from his Schwinn Sting-Ray; now walking upright with his car keys in hand; now striding away from home holding a suitcase.

The question I got most often as a child in the 1970s was What do you want to be when you grow up? My answers varied along the usual lines of fantasyfireman, Vikings wide receiver, authorbut the question also could be taken at face value: what do you want to be, as in how do you want to live, where do you want to live, what kind of person will you become?

For me, that becoming happened in the 1980s between the ages of thirteen and twenty-two. For forty-five minutes on that spring night in 1979with an endless string of nights laid out before them like runway lightsJim and Fluff play-acted as workers at White Castle. But their complementary futures had already taken shape: Jim would play ice hockey in college while Fluff would study dentistrythe symbiotic pursuits of best friends.

I was in seventh grade in 1979, and what I wanted to become was Jim: high school athlete, unflappable prankster, cinematic tough guy. For many years, without provocation, Jim made a highly specific threat to his three brothers: I will rip your lips off. It wasnt until he left home for goodand I was in high school myself, frequenting the Castle on weekend nightsthat I could pass his former bedroom door without clamping my lips together in self-protection.

When the five Rushin children were still under one roof, we gathered on rare occasions at the kitchen table and played Milton Bradleys The Game of Life. As in actual life, The Game of Life encouraged participants to attend college, get a job, fall in love, amass a fortune, and have children in the form of pink or blue plastic pegs that plugged into little plastic cars. Those cars sometimes crashed, triggering hospital bills and higher insurance premiums. Luckier players got stock dividends or identical twins. Lifeand for all I knew, lifewas a zero-sum game. It could only end at one of two places: Millionaire Acres or the Poor Farm.

At the center of the board was a wheel of fortune. I would sometimes spin it as a solitary pursuit, just to see what number came up. The following pages are set during that quicksilver timehigh school, college, and leaving home foreverwhen the great wheel is still spinning and, for a moment at least, everything in life remains possible.

In the High School Halls,

in the Shopping Malls

T here are two masterworks called 1984 that the Class of 1984 has to reckon with. The first is required reading for seniors at John F. Kennedy High School, whose address is stamped all over the Signet Classics in our hands. Those addresses are a theft deterrent, the exploding dye in a bank robbers bag of cash, meant to shame and identify a would-be thief, though who would want to steal a copy is an open question in room 101. As if, says a girl in front of me. Her friend replies: I know, right?

On page 9, deeper than most of my classmates will make it into Orwells dystopia, Winston Smith sees a book in the window of a London junk shop and is stricken immediately by an overwhelming desire to possess it. I know the feeling. Fanning the pages of the paperback, I see a stick figure drawn in blue ballpoint by a previous student spring to life in flip animation. He runs across the upper-right corner of every right-hand page of the book in a futile effort to escape. Its what many of us here want to do.