Contents

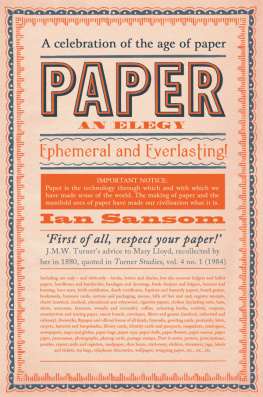

IAN SANSOM is the author of Paper: An Elegy and the Mobile Library Mystery series of novels. He is also a frequent contributor to the Guardian and the London Review of Books, and a regular broadcaster on BBC Radio 3 and Radio 4.

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

www.4thestate.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2015

Copyright Ian Sansom 2015

Cover image Science & Society Picture Library / Getty Images

Ian Sansom asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks.

Source ISBN: 9780007533169

Ebook Edition January 2015 ISBN: 9780007533152

Version: 2016-12-08

For Will

And Babylon, the glory of kingdoms, the beauty of the Chaldees excellency, shall be as when God overthrew Sodom and Gomorrah. It shall never be inhabited, neither shall it be dwelt in from generation to generation: neither shall the Arabian pitch tent there; neither shall the shepherds make their fold there. But wild beasts of the desert shall lie there; and their houses shall be full of doleful creatures; and owls shall dwell there, and satyrs shall dance there. And the wild beasts of the islands shall cry in their desolate houses, and dragons in their pleasant palaces: and her time is near to come, and her days shall not be prolonged.

Isaiah 13:1922

AH, SEFTON, MY FECKLESS FRIEND, said Morley. Just the man. Now. Rousseau? What do you think?

He was, inevitably, writing one of his inevitable articles. The interminable articles. The inevitable and interminable articles that made up effectively his one, vast inevitable and interminable article. The ber-article. The article to end all articles. The grand accomplishment. The statement. What he would have called the magnum bonum. The Gesamtkuntswerk. An essay a day keeps the bailiffs at bay, he would sometimes say, when I suggested he might want to reduce his output, and The night cometh when no man can work, Sefton. Gospel of John, chapter nine, do you know it? I knew it, of course. But only because he spoke of it incessantly. Interminably. Inevitably. It was a kind of mantra. One of many. Swanton Morley was a man of many mantras of catchphrases, proverbs, aphorisms, slang, street talk and endless Latin tags. He was a collector, to borrow the title of one of his most popular books, of Unconsidered Trifles (1934). It takes as little to console us as it does to afflict us. Respice finem. And May you never meet a mouse in your pantry with tears in his eyes. Morleys endless work, his inexhaustible sayings, were, it seemed to me, a kind of amulet, a form of linguistic self-protection. Language was his great superstition and his saviour.

To stave off the universal twilight that evening Morley had rigged up the usual lamps and candles, and had his reams of paper piled up around him, like the snow-capped peaks of the Karakoram, or faggots on a pyre, like white marble stepping stones leading up to the big kitchen table plateau, where reference books lay open to the left and to the right of him, pads and pens and pencils at his elbow, his piercing eyes a-twinkling, his Empire moustache a-twitching, his brogue-booted feet a-tapping and his head a-nodding ever so slightly to the rhythms of his keystrokes as he worked at his typewriter, for all the world as if he were an explorer of some far distant realm of ideas, or some mad scientist out of a fantasy by H.G. Wells, strapped to an infernal computational machine. A glass and a jug of barley water were placed beside him, in their customary position his only indulgence.

It was already well after midnight. I had returned to Norfolk and St Georges after two days in London, attempting to put my affairs in order and succeeding only in disordering them further.

Rousseau? I said. It was my job in these exchanges, I had soon realised, to bat the ball gently back to him, the warmup to his Fred Perry, as it were, throwing him balls or titbits, that he might leap up and devour them. My interlocutor, he would sometimes introduce me to new acquaintances, or, alas, worse, My bo, one of those terribly unfortunate phrases hed picked up from his beloved hard-boiled detective stories, and which got us into a number of scrapes over the years. Damon Runyon, Ellery Queen: I could never quite understand his enthusiasm for purveyors of what he might, in the argot, have called shtick.

Rousseau. Yes. I was finding it hard to think. I had, admittedly, in London, been drinking and indulging, even though I had promised myself not to return to my former habits and haunts, but had found it impossible to resist. Just forty-eight hours away from Morley and his high thinking and I had descended back down to the depths of my depravities.

Come, come, Sefton. Rousseau? He clapped his hands.

Well Id managed to catch the last train out of Liverpool Street for Norfolk, in the full knowledge that if I stayed a day longer the die would be cast for ever, and I would be adrift and out of employment again, at the mercy of Messrs Gabbitas and Thring, and worse

Hello? Dial 0 for operator? He rapped his knuckles against the table. Hello? Operator? Its ringing for you, caller! Remind me why I employed you again, Sefton?

I had at that stage been Swanton Morleys amanuensis, his assistant, and his bo for approximately two weeks. And I had to admit that apart from my time in Spain it had been the strangest, most utterly disorientating and exhilarating two weeks of my life. It had also not insignificantly helped to solve certain personal and practical problems I had been facing in London. Which is why, after a hectic few days, I had returned again to the wilds of Norfolk ready to clock in promptly for work on Monday morning.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, I offered, fossicking around in my rather disordered mental store cupboard. Philosopher. Educationalist

No! No! No! Come on, man. Wrong Rousseau! said Morley. Henri. Or Henri, pronounced in the continental fashion.

Ah. As if I should have known which continental Rousseau he had in mind.

Here, here. Come, come, come.

Morley beckoned me towards him. I edged carefully around the books and papers and looked over his shoulder at one of the large volumes spread out on the desk.

Well. What do you think of that?

The moon shone down brightly from the high window above the table, illuminating the book, which showed an illustration of an extraordinarily vivid, disturbed sort of painting, like the work of a brilliantly gifted child, depicting what was presumably supposed to be a lion sinking its teeth into what was presumably an

Next page