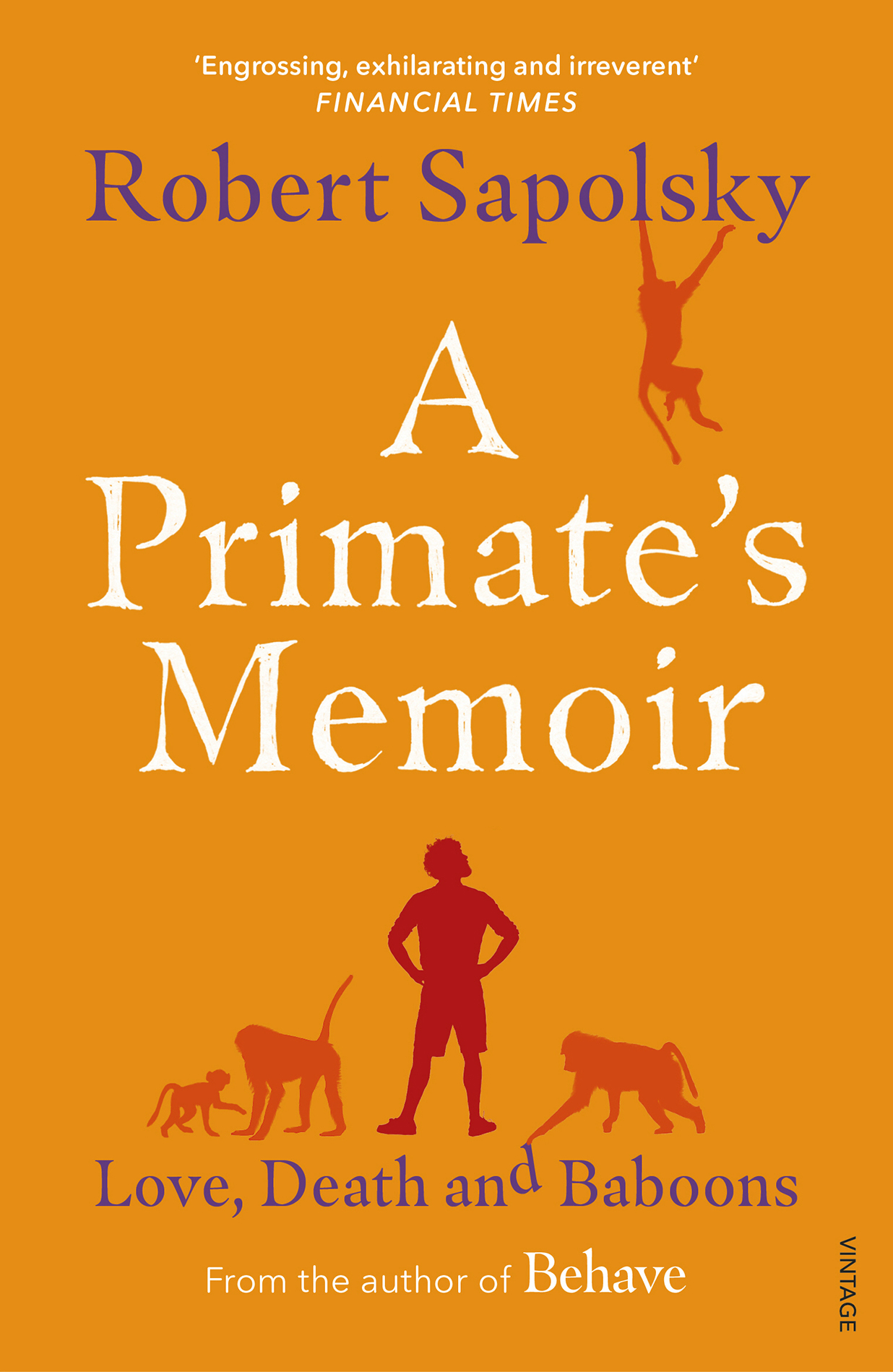

ROBERT SAPOLSKY

A Primates Memoir

Love, Death and Baboons

Contents

About the Author

Robert M. Sapolsky holds degrees from Harvard and Rockefeller Universities and is currently a Professor of Biology and Neurology at Stanford University and a Research Associate with the Institute of Primate Research, National Museums of Kenya. He is the author of The Trouble with Testosterone, Why Zebras Dont Get Ulcers (both finalists for the LA Times Book Award), A Primates Memoir and Behave. Sapolsky has contributed to Natural History, Discover, Mens Health, and Scientific American, and is a recipient of a MacArthur Foundation genius grant.

ALSO BY ROBERT SAPOLSKY

Monkeyluv and Other Essays on Our Lives as Animals

The Trouble with Testosterone and Other Essays on the Biology of the Human Predicament

Why Zebras Dont Get Ulcers: A Guide to Stress, Stress-Related Diseases, and Coping

Stress, the Aging Brain, and the Mechanisms of Neuron Death

Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst

To Benjamin and Rachel

Acknowledgments

This is a memoir of my more than twenty years spent working intermittently in a national park in East Africa. The stories are true but, as is often the case in such retellings, subject to a bit of literary license that I want to describe here. The story of Wilson Kipkoi is true in most details. However, names and some other details have been changed to protect anonymity. The final chapter, unfortunately, is true in all its devastating details; however, here, too, I have changed names and certain characteristics. The chronology of the various chapters has been expanded in some places, truncated in others. In a few cases, the sequence of some stories has been changed; the sequence of all events in the lives of the baboons, however, is unchanged. Finally, a number of humans, and a number of baboons, represent composites of a few members of their species. This was done to keep down the cast of characters coming and goingfor example, within the human realm, a particular game-park ranger, British tour operator, or tourist-lodge waiter may be a composite of a few individuals. All of the major baboon figures are real individuals, as are the major human charactersRichard, Hudson, Laurence of the Hyenas, (the late) Rhoda, Samwelly, Soirowa, Jim Else, Mbarak Suleman, Ross Tarara, and, of course, Lisa are all real people. I, to the best of my knowledge, am not a composite.

A number of individuals helped me with fact checking, reading part or all of this book or, in the case of Soirowa, who cannot read, having sections in it related, in order to confirm the accuracy of facts as they remember them. As such, I thank Jim Else, Laurence Frank, Richard Kones, Hudson Oyaro, and Soirowa. I also thank Colin Warner for some formal fact checking in the library, and John McLaughlin, Anne Meyer, Miranda Ip, and Mani Roy for help in proofreading the manuscript. Dan Greenwood and Carol Salem shared stories with me of their travels in East Africa, and I thank them for that. I thank Jonathan Cobb, Liz Ziemska, and Patricia Gadsby for their priceless editorial advice when reading what was a proto-version of this book, a number of years ago.

Funding for this work was made possible by the Explorers Club, the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, and the Templeton Foundation. I thank them not only for their generosity but for their extraordinary flexibility in recognizing the peculiar exigencies of fieldworkat the very least, I thank them for accepting receipts and budget summaries on waterlogged, moth-eaten (literally) accounting notebooks. I thank the Institute of Primate Research, National Museums of Kenya, for my association with them, and the Office of the President, Republic of Kenya, for permission to conduct my research all these years. Two colleaguesShirley Strum of the University of California at San Diego, and Jeanne Altmann, of Princeton University, have opened their field sites to me as part of our collaborations, and I thank them for that experience. And I thank a number of individuals who taught me aspects of doing fieldwork or helped me with data collection during some of the early seasonsDavie Brooks, Denise Costich, Francis Onchiri, and Reed Sutherland.

I thank my agent, Katinka Matson, for her tremendous support and expertise in making this book a reality, and Gillian Blake, my editor, and Rachel Sussman, her assistantyou have been remarkably graceful in pointing out problems in this manuscript that anyone but a scientist should have learned back in Creative Writing 101. It has been a pleasure working with you all.

And finally, I thank my wife, Lisa, the love of my life, who has shared so many of these moments in Kenya with me.

A final note: The depredations and plunderings of colonialism in Africa are now a thing of the past. However, the West often continues to exploit Africa in far subtler ways, even on those occasions when intentions are the best. I have now spent more than half my life connected with Africa, and I have intense feelings of warmth, respect, and gratitude for the place and my friends there. I deeply hope that I have not inadvertendy been exploitative in any way in these writings. This was the last thing I would have intended.

PART 1

The Adolescent Years: When I First Joined The Troop

1

The Baboons: The Generations of Israel

I joined the baboon troop during my twenty-first year. I had never planned to become a savanna baboon when I grew up; instead, I had always assumed I would become a mountain gorilla. As a child in New York, I endlessly begged and cajoled my mother into taking me to the Museum of Natural History, where I would spend hours looking at the African dioramas, wishing to live in one. Racing effortlessly across the grasslands as a zebra certainly had its appeal, and on some occasions, I could conceive of overcoming my childhood endomorphism and would aspire to giraffehood. During one period, I became enthused with the collectivist utopian rants of my elderly communist relatives and decided that I would someday grow up to be a social insect. A worker ant, of course. I made the miscalculation of putting this scheme into an elementary-school writing assignment about my plan for life, resulting in a worried note from the teacher to my mother.

Yet, whenever I wandered the Africa halls in the museum, I would invariably return to the mountain gorilla diorama. Something primal had clicked the first time I stood in front of it. My grandfathers had died long before I was born. They were mythically distant enough that I would not be able to pick either out in a picture. Amid this grandfatherly vacuum, I decided that a real-life version of the massive, sheltering silverback male gorilla stuffed in the glass case would be a good substitute. A mountainous African rain forest amid a group of gorillas began to seem like the greatest refuge imaginable.

By age twelve, I was writing fan letters to primatologists. By fourteen, I was reading textbooks on the subject. Throughout high school, I finagled jobs in a primate lab at a medical school and, finally, sojourning to Mecca itself, volunteered in the primate wing of the museum. I even forced the chairman of my high school language department to find me a self-paced course in Swahili, in preparation for the fieldwork I planned to do in Africa. Eventually, I went off to college to study with one of the deans of primatology. Everything seemed to be falling into place.

Next page