Metropolitan Books

Henry Holt and Company, LLC

Publishers since 1866

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, New York 10010

www.henryholt.com

Metropolitan Books and are registered trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC.

are registered trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC.

Copyright 2009 Beryl Satter

All rights reserved.

Distributed in Canada by H. B. Fenn and Company Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Satter, Beryl, 1959

Family properties : race, real estate, and the exploitation of Black urban America /

Beryl Satter.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8050-7676-9

ISBN-10: 0-8050-7676-X

1. African AmericansHousingIllinoisChicagoHistory20th century. 2. Discrimination in housingIllinoisChicagoHistory20th century. 3. Housing policyIllinoisChicagoHistory20th century. 4. African AmericansIllinoisChicagoSocial conditions20th century. 5. African AmericansRelations with Jews. 6. Chicago (Ill.)Social conditions20th century. 7. Chicago (Ill.)Race relationsHistory20th century. 8. Satter, Mark J., 19161965. 9. LawyersIllinoisChicagoBiography. 10. LandlordsIllinoisChicagoBiography. I. Title.

HD7288.76.U52C434 2009

363.5'9996073077311dc22 2008033005

Henry Holt books are available for special promotions and

premiums. For details contact: Director, Special Markets.

First Edition 2009

Maps by James Sinclair

Designed by Kelly S. Too

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

ALSO BY BERYL SATTER

Each Mind a Kingdom

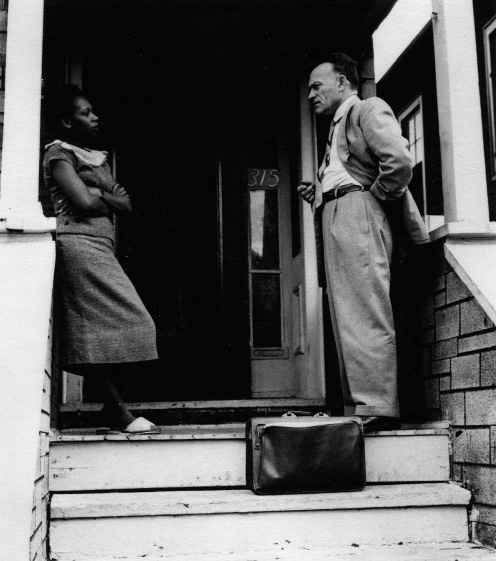

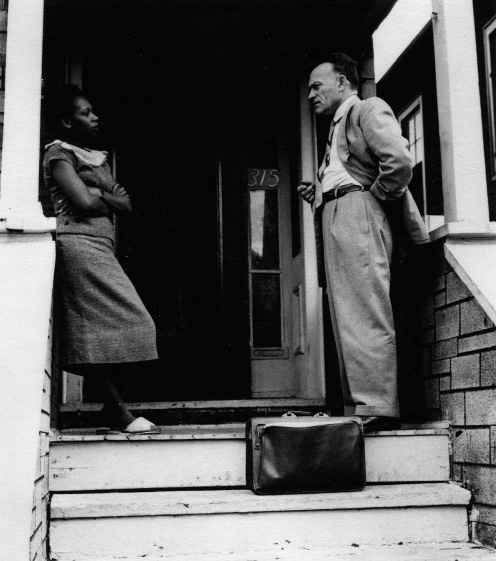

Mark J. Satter with unidentified woman (probably a client, probably around 1958). Date, place, photographer unknown.

To my brother, Paul Satter

and

in memory of Maureen McDonald

INTRODUCTION

THE STORY OF MY FATHER

When an elderly woman erupts into shouts of rage at the mere mention of events now forty years past, you know there is a story there. In the winter of 2000 I asked my aunt what had become of my fathers buildings after he died. I should have known by then that nothing connected with my fatheror with property, especially property owned by Jews in black neighborhoods, and especially in Chicagowas simple.

I was six years old when my father died. He had a heart condition that slowly destroyed him. On his third hospital stay, with his wife and one of his sons at his side, Mark J. Satter went into convulsions. At around 2:00 a.m., he called out words of warning: Look out! Later! Watch it! And then he died. It was July 12, 1965. He was forty-nine years old.

A period of confusion followed. At first, my mother tried to talk to me and my older brothers and sisters about the man my father had been. He was an independent attorney who used the law to help the poorblack people in particular; our family was on the side of black people. He was respected in our city, and we should be proud to be his children. Although my mother was never very specific about my fathers accomplishments, I had reason to believe her. She framed an editorial obituary that was published in the Chicago Daily News: Satter was the kind of man who made enemiesbig and comfortable ones, not poor and weak ones. that was a good thing. And then there were the condolence letters. There were stacks of them. They praised Mark J. Satter as the citys conscience. They told my mother that her loss was the citys loss as well. They insisted that her husband was a great man and that his legacy would not be forgotten.

It wasnt long, however, before discussion of my father ceased almost entirely. My sisters and I squirmed with discomfort on the occasions that our mother mentioned him. He had passed away, my mother said, so why did we need to hear about him? The rare comments my aunts and uncles made about him grew increasingly negative. He left my mother in a terrible state, bankrupt and dependent on Social Security checks, Jewish social services, and one of my uncles for financial support. How could he do that to her? The recollections of my two older brothers, who had been sixteen and seventeen when my father died, turned bitter. He was driven to run a race that he could not win, my brother David recalled. Unfortunately, he pulled the rest of us into it with him.

And then there were the buildings. My father had owned several apartment buildings in Lawndale, an old Jewish neighborhood on Chicagos West Side that had become almost entirely black by the late 1950s. They had been sold, I eventually learned, shortly after my fathers death. A friend of his named Irving Block had helped my mother get rid of them. But the sale had brought nothing to the family, not even money to pay the properties coal bills.

The talk about the buildings confused me. I had heard scraps of discussion about these mysterious structures from earliest childhood. My brother Paul would mention them to my mother, it seemed to me, mainly to upset her. Why did you sell the buildings? Everything would have been fine if you hadnt sold them! I would chime in, too: What buildings? I would press. Nothing, never mind, dont bother me! Dont talk to me about those buildings! my mother would respond, her voice sharp with irritation and pain. It was one of the few topics that could shake her composure.

It was hard to reconcile the tales of my fathers prominence with the financially cramped circumstances of my childhoodand with my relatives odd reticence about him. As I got older I tried to learn about him on my own. My main source of information was a notebook filled with newspaper clippings that Paul compiled soon after my fathers death. The I gave up in frustration. By the time I got to college I told friends that my father had been some sort of civil rights attorney, but that was the extent of my understanding of his work.

Given the mysteries of my familys past, perhaps it is no surprise that I became a historian. But it was not until some thirty years after my fathers death that I decided to find out more about him. I wanted to understand the source of his public prominenceand discover, as well, the reasons my relatives steadfastly refused to laud him for his activism. I could not ask my mothershe had died in 1983. But my brother Paul again came to the rescue. It turned out that he had compiled not one but close to a dozen large notebooks full of newspaper articles, letters, speeches, and other documents pertaining to my fathers career. I read through them systematically. Then I started calling people who had known my fatherreporters, friends, fellow activists, clients, and legal partners. They werent hard to findmany were still listed in the Chicago phone book. Most remembered him instantly, as if his death had occurred a week rather than over three decades earlier. Each person I called gave me contact information for several others. Then I retrieved my fathers legal files. I scoured archives and manuscript collections, examining the papers of civic organizations hed belonged to and those hed opposed. Slowly, the picture came clear.

The first thing I learned was that my father had represented scores of African Americans who had been grossly overcharged for the houses they had bought. For him, it all began in April 1957, when a black couple, Albert and Sallie Bolton, showed up at his office. They were being evicted from their home and they wanted him to delay the proceedings. My father agreed to look into the matter. He asked what they had paid for their property. When they told him, he was astounded. They had paid the enormous sum of $13,900 for a cramped, one-hundred-year-old wood-frame house. My father investigated the property records. He discovered that the white real estate agent, Jay Goran, who had sold the cottage to the Boltons in the fall of 1955, had himself purchased the building only the week beforefor $4,300.

are registered trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC.

are registered trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC.