Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

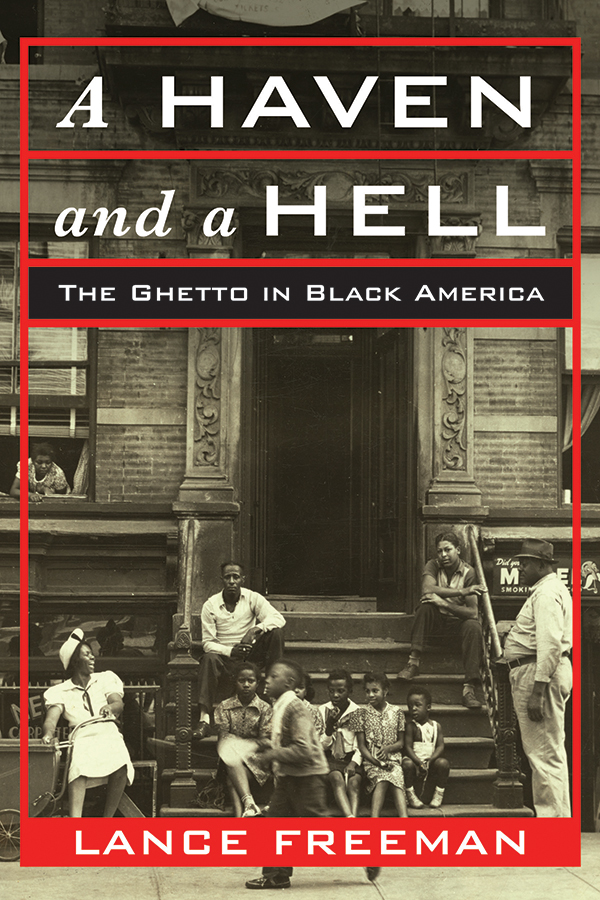

A HAVEN AND A HELL

A Haven and a Hell

THE GHETTO IN BLACK AMERICA

Lance Freeman

Columbia University Press

New York

CONTENTS

I thank Hyun Hye (Cathy) Bae for her tremendous assistance in completing this book. Brianna Peppers also was of great help in sourcing archival materials. My colleagues Derek Hyra and Rachael Woldoff offered encouragement and thoughtful feedback on my ideas for the book. My editor, Eric Schwartz, provided invaluable guidance in shepherding the book to completion.

Finally, I thank my mother, Eleanor Freeman, who I wish had lived to see the completion of this project.

His was a true rags-to-riches-to-rags story. After working as a barber and Pullman Porter in sundry western cities, he arrived in Chicago in the late 1890s with only a few dollars. He went on to build a real estate and financial empire that inspired awe and pride among members of his race. By the third decade of the twentieth century, he could boast of a bank bearing his name, a bank reputable enough to become one of the few on the South Side of Chicago to belong to the association of elite Chicago banksthe Chicago Clearing House Association.

Jesse Bingas rise paralleled the rise of Chicagos black ghetto in the early twentieth century. Indeed, in many ways Binga rose to fame and fortune because of the rise of the ghetto. He made his fortune buying white-owned properties and opening these properties up to space-starved Negroes. His bank and insurance company provided financial services to a clientele shunned by white-owned banks. He also married into money, wedding the sister of John Mushmouth Johnson, who made his fortune providing another service to the captive Negro audienceillegal gambling or numbers. In short, the ghetto created a captive market that an enterprising Jesse Binga capitalized on to make his fortune.

Binga was no mere bystander to the rise of the ghetto. Aside from making his fortune off the ghetto, he acted to shape the ghetto, both the institutions within it, such as his bank, and its physical boundaries. To be sure, white racism and a refusal to have Negroes as neighbors gave rise to a color line that hemmed Negroes inside the ghetto. But Binga was an active participant in determining where the color line and boundaries of the ghetto would be drawn. In acquiring white-owned properties, he was carving out space for blacks in what was formerly hostile white territory. The acquisition of properties by race men such as Jesse Binga meant additional housing opportunities for the race. The expectation was that once property fell into a race mans hands, it would be made available to black families. Indeed, Binga was often depicted as a champion of the races interests as he acquired property in formerly all-white neighborhoods, displaced the current occupants, and opened these same properties to Negroes.

The ghetto was instrumental in Jesse Bingas rise, and it would play a key role in his downfall as well. The proximate cause of Bingas collapse, which culminated in the demise of his bank and his imprisonment for fraud, was the Great Depression. Personal shortcomings and a proclivity for mixing the banks finances with his own played their role as well.

A HAVEN AND A HELL

Jesse Bingas story illustrates the twofold nature of the relationship between the ghetto and black America. Although much has been spoken and written about the ills of the ghetto, this perspective tells only one side of the story. Thanks to the work of numerous historians, we know the modern ghetto was the result of blacks migrating en masse to urban centers in the early twentieth century and creating new types of urban spaces heretofore unseen on the American landscape. The term ghetto , initially used to define a space where Jews in sixteenth-century Italy were confined, seemed an apt moniker for these spaces inhabited by blacks. Like the Jews in the ghettos of Venice, blacks were confined to specific spaces. Moreover, these spaces were marginalized, stigmatized, and typically undesirable. Ghetto residents in both medieval Venice and urban America were stigmatized for residing in these spaces. Moreover, whatever their compunctions about residing in the ghetto, its inhabitants, then and now, had little choice about residing there. The ghetto, whether in its sixteenth century incarnation or its modern one, was not the result of Jews or blacks voluntarily congregating together.

Unlike the ghetto of Venice, however, black ghettos grew in size and salience so that at various times they have been viewed as Americas most pressing problem. Given the ghettos salience in Americas urban life, it is not surprising that scholars have produced a voluminous scholarship on it. We know that white racism manifested through private actors was largely responsible for spawning the ghettos in the early twentieth century. Historians have also shown how federal and local governments became senior partners in reinforcing and expanding the walls of the ghettos starting during the Great Depression and extending several decades thereafter.

We know that ghettoization made it difficult for blacks to participate in the American Dream of upward mobility and stability through homeownership as they were either denied access to homeownership or relegated to owning property in declining neighborhoods where ownership proved a dicey proposition. We also know that the confinement of blacks to the ghetto has made the celebrated Brown v. Board of Education victory in 1954 a hollow one across dozens of northern cities as black children still attend segregated schools more than half a century later.

Furthermore, the relegation of blacks to the inferior ghetto and white flight in combination precipitated an urban crisis in which many of American cities faced bankruptcy as they struggled to support a poor and declining population on a steadily dwindling tax base. Social scientists have also shown that living in the ghetto has stunted the life chances of millions of blacks. The toll of inferior schools, higher crime, lack of jobs, and social isolation has only marginalized ghetto residents even further.

Thus, the ghettos role as a hell for black Americans is clear. The ghetto has served as an instrument of subjugation for blacks. Like slavery and Jim Crow, it has been an institution that stifles dreams and serves the interests of others.

But the ghetto has also been more than that. As Jesse Bingas experience illustrates, the ghetto has been a haven, too, a place where many have improved their lot. Although Bingas rise and fall were dizzying, for many blacks the ghetto has provided incremental but extremely important steps toward a better life and fuller inclusion in American society.

This book chronicles the role of the ghetto as an institution in influencing black American life. The spatial and temporal focus of the book is expansive, which means some specific factors are glossed over or excluded altogether. Perhaps most importantly, this book focuses on ghettos outside of the eleven states that were part of the Confederate States of America during the Civil War. Although ghettos did and do exist in the South, the race relations and economic context were different enough during vast stretches of the period studied to warrant the exclusion of this region here. Nevertheless, even outside the South there were significant differences between ghettos in various parts of the countrysay, Harlem in New York and Watts in Los Angeles. There are a number of excellent histories of specific ghettos, which I draw on. A close reading of these histories, however, reveals that these communities as institutions in black life share a number of similarities that allow for a cogent general narrative about ghettos outside the southern United States.