Copyright 2017 by Gerda Saunders

Cover design by Amanda Kain

Cover copyright 2017 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Hachette Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

hachettebooks

twitter.com/hachettebooks

First ebook edition: June 2017

All images courtesy of the author, except for the following: Cheryl Saunders. Images used with permission.

Hachette Books is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Hachette Books name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ISBN 978-0-316-50263-4

E3-20170504-JV-PC

For my made-in-America familynow too extended to namethe friends of my heart who are now blood

for the Salt Lake City Saunderses: Kanye, Aliya, and Dante, and those people who transport them to visit Ouma and Oupa

and, of course, for Peter: , where elephants shelter when the heavens frown.

When I was diagnosed with early-onset dementia just before my sixty-first birthday in 2010, I kept my hurt, anger, fear, and doubts under wraps. I had no choice. I had a job, a husband, children, grandchildren, friends. I had a life. However, there is nothing like a death sentencein my case, the premature death of my mindto provoke questions about life. What, actually, is memory, personality, identity? What is a self? Will I still be (have?) a self when my reason is gone? For me, the place to work out such questions has always been in writing. From that place of self-reckoning, then, came this book.

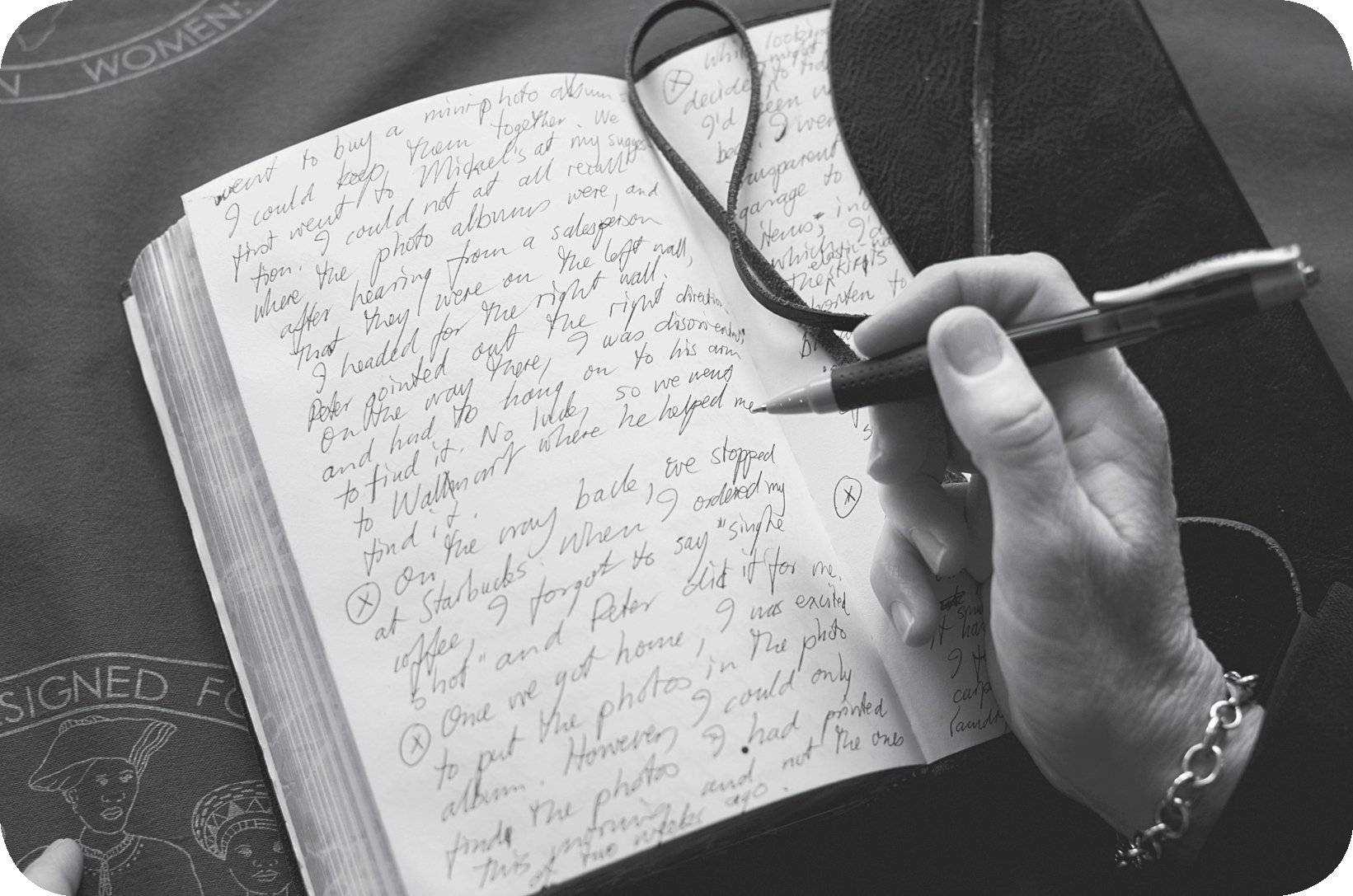

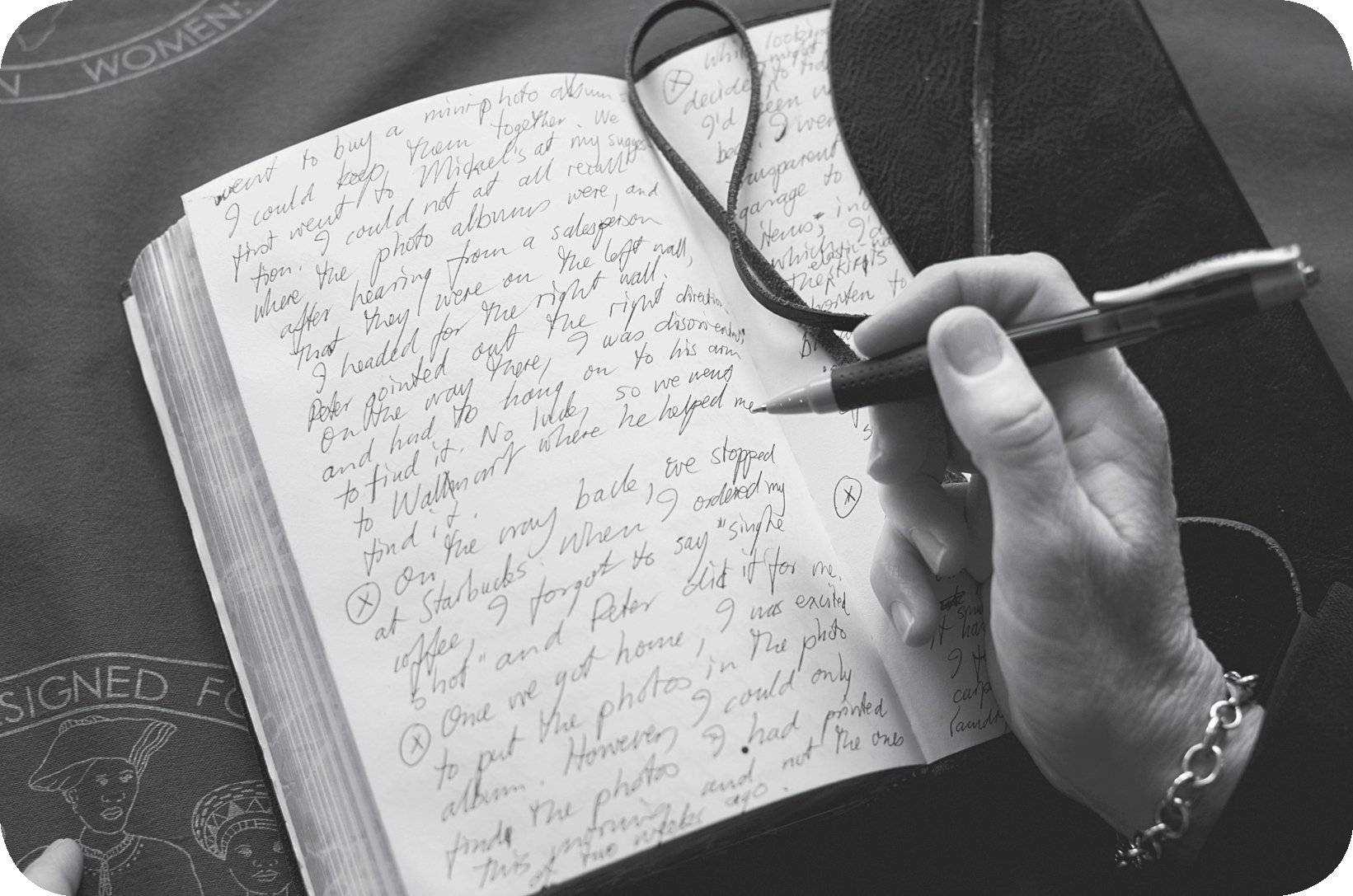

In July 2011nine months after my diagnosiswhen I retired from my position as the associate director of the Gender Studies Program at the University of Utah, my colleagues gave me a beautiful leather-bound journal as a goodbye present. I took to jotting down notes in it about my daily misadventurespots on the stove boiling dry, washing my hair twice in an hour, forgetting to bake a casserole I had prepared the night before. With a wink at my background in the sciences, I called my journal Dementia Field Notes: I would be an anthropologist, assigned to observe one member of a strange tribe, the Dementers. Like a true scientist, I would be objective. No whining, wailing, or gnashing of teeth. Just the facts.

A month or two into my objective writing, I also started to write a personal narrative about my dementia. Objectivity be damned. I felt compelled to tell my story from the inside. Months later, the piece turned into an essay. After some tough-love editing by two of my closest friendsShen Christenson and Kirstin Scott, both writersI showed the essay to my husband, Peter, my children Marissa and Newton and their spouses, and a few close friends. They urged me to share the essay with others and, to my delight, demanded I write more.

I wrote a second essay, which included summaries of neurological research into various forms of dementia. The idea that my writing might add up to a book slowly started to take shape. Two and a half years after my first Field Notes entry, I had completed three essays. I was mentally exhausted. I had little energy left to enjoy my life. My working memorythe ability to hold a small amount of info in my head while using it, such as remembering the street name and street number as I wrote down an address while someone said it on the phonebarely functioned. Neuropsychological tests showed a decline in my IQ. I began to question if writing a book was worth these losses. Was this how I wanted to spend my remaining good years?

I decided to end my excursion into writing with a bang. Starting in September 2012, I mined my completed essays for passages that would add up to a stand-alone piece for publication. The result was published as Telling Who I Am before I Forget: My Dementia in the Winter 2013 issue of the Georgia Review (GR) and subsequently reprinted in the large-circulation online magazine Slate. That a Slate editor would even notice my essay in an academic journalthough it consistently ranks first or near the top of its peers on Pushcarts list of nonfiction journalshad been a matter of great serendipity. But Dan Kois is not just any editorhaving started out at Slate as culture editor, he made a habit of reading academic journals for reprint possibilities. While Kois cruised the publishers displays at the 2014 conference of the Association of Writers and Writing Programs, the editor managing GRs booth handed him a copy of the Winter 2013 issue and mentioned my essay, in Dans words, as one they were particularly enthusiastic about. (Blessings on the Georgia Reviews extraordinary staff!)

To my surprise, the Slate essay was reviewed or recommended in publications ranging from an NYU School of Medicine newsletter to Business Insider to the New Yorker. While this recognition stroked my ego, the comments, questions, and contacts I received from readers expanded my heart, particularly those from people who had dementia in their families. My family had been right in thinking that my writing on dementia could be useful in the worldthat perhaps, in exploring my own experience on the page, I could in some way help shed light on the confusion, embarrassments, hurt feelings, and shrinking self-image that many people with dementia experience. Inevitably, my Calvinist upbringing kicked in: It was my duty to continue the book. And then, out of the blue, an email arrived one day from the sine qua non Kate Garrick, a literary agent in New York. Under her watchful eye, I wrote more essays. In time, Kate helped me see that they almost added up to an autobiography. But not quite. Large chunks of my life were missing. During the next two years, Kate nursed me through additions and revisions, a process during which I sometimes got so lost in the manuscript that I almost gave up. My reward for going on was that, in the end, my manuscript provided a glimpse into the full arc of my life. In February 2016, Kate sold my manuscript to Hachette Books, where my editor, the thoughtful perfectionist Paul Whitlatch, helped me shape the somewhat flabby manuscript into the book you now hold in your hands.

My book is for this: to add my personal story to the body of science about dementia already accumulated by the lifetime efforts of neuroscientists, neuropsychologists, other medical researchers, and healthcare providers.

My book is for you: whether you or someone you love has dementia, or youre a medical professional, or a person searching for your own self after a huge life change, or someone just plain curious, wholike mefeels that the more you know, the better youre able to love.