50 Years of Publishing

1945-1995

First published by Schocken Books in 1949

First Schocken Paperback edition published in 1963

Copyright 1949 by Schocken Books Inc.

Copyright renewed 1977 by Schocken Books Inc.

All rights reserved

under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York.

Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of

Random House, Inc., New York.

Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 63-11040

eISBN: 978-0-307-49369-9

v3.1

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

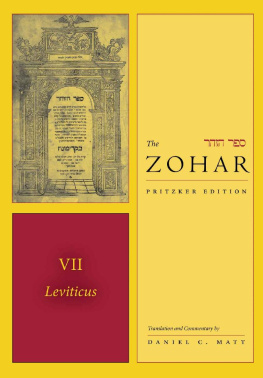

HISTORICAL SETTING OF THE ZOHAR

The book of Zohar, the most important literary work of the Kabbalah, lies before us in some measure inaccessible and silent, as befits a work of secret wisdom. Whether because of this, or in spite of it, among the great literary products of our medieval writings, however much clearer and more familiar than the Zohar many of them seem to us, not one has had an even approximately similar influence or a similar success. To have determined the formation and development over a long period of time of the religious convictions of the widest circles in Judaism, and particularly of those most sensitive to religion, and, what is more, to have succeeded in establishing itself for three centuries, from about 1500 to 1800, as a source of doctrine and revelation equal in authority to the Bible and Talmud, and of the same canonical rankthis is a prerogative that can be claimed by no other work of Jewish literature. This radiant power did not, to be sure, emanate at the very beginning from The Book of Radiance or, as we usually render the title in English, The Book of Splendor. Maimonides Guide to the Perplexed, in almost every respect the antithesis of the Zohar, influenced its own time directly and openly; from the moment of its appearance it affected peoples minds, moving them to enthusiasm or to consternation. Yet, after two centuries of a profound influence, it began to lose its effectiveness more and more, until finally, for centuries long, it vanished almost entirely from the consciousness of the broad masses. It was only at the end of the 18th century that the Jewish Enlightenment again brought it into prominence, seeking to make it an active force in its own struggle.

It was different with the Zohar, which had to make its way out of an almost complete, hardly penetrable anonymity and concealment. For a hundred years and more it elicited scarcely any interest to speak of. When it came on the scene, it expressed (and therefore appealed to) the feeling of a very small class of men who in loosely organized conventicles strove for a new, mystical understanding of the world of Judaism, and who had not the faintest notion that this particular book alone, among the many which sought to express their new world-view in allegory and symbol, was destined to succeed. Soon, however, the light shadow of scandal that had fallen upon its publication and initial appearance in the world of literature, the enigma of the illegitimate birth of a literary forgery, disappeared and was forgotten. Very slowly but surely the influence of the Zohar grew; and when the groups among which it had gained dominion proved themselves in the storms of Jewish history to be the bearers of a new religious attitude that not only laid claim to, but in fact achieved, authority, then the Zohar in a late but exceedingly intensive afterglow of national life came to fulfil the great historical task of a sacred text supplementing the Bible and Talmud on a new level of religious consciousness. This inspirational character has been attached to it by numerous Jewish groups in Eastern Europe and the Orient down to our own days, nor have they hesitated to assert that final conclusion which has since earliest times been drawn in the recognition of a sacred text, namely, that the effect upon the soul of such a work is in the end not at all dependent upon its being understood.

It was only with the collapse of that stratum of life and belief in which the Kabbalah was able to represent a historical force that the splendor of the Zohar also faded; and later, in the revaluation of the Enlightenment, it became the book of lies, considered to have obscured the pure light of Judaism. The reform-tending polemic in this case too made haste to become an instrument of historical criticism, which, it must be said, after a few promising starts, showed itself weak and uncertain in the carrying out of its program, sound as its methods and true as many of its theses may have been.

Historical criticism, however, will survive the brief immortality of that genuine Judaism whose view of history and whose hierarchy of values gave rise to it. Freed from polemic, and concerned for a more precise and objective insight into its subject matter, it will now assert itself in the new (and in part very old) context in which we begin to see the world of Judaism, and Judaisms history.

LITERARY CHARACTER

The Zohar in its external literary physiognomy seems far from being conceived and constructed as a unified composition. Still less can it be regarded as any kind of systematic exposition of the world-view of the Kabbalah, like many such which have come down to us from the period of the Kabbalahs origin and even more from later times. It is rather, in the printed form that lies before us, a collection of treatises and writings that are considerably different from one another in external form. Most of the sections seem to be interpretations of Bible passages, or short sayings or longer homilies, or else often artfully composed reports of whole series of homilies in which Rabbi Simeon ben Yohai, a famous teacher of the 2nd century, and his friends and students interpret the words of Scripture in accordance with their hidden meaning, and, moreover, almost always in the Aramaic language. Other sections, though these are few, have been presented in the form of anonymous and purely factual accounts in which there can be recognized no such settings of landscape and persons as those described with so much care elsewhere in the work, often in highly dramatic fashion. Fairly often the exposition is enigmatically brief, but frequently the ideas are very fully presented with homiletical amplitude and an architectonically effective elaboration. Many sections actually appear as fragments of oracles and as reports of secret revelations, and are written in a peculiarly enthusiastic, a solemn, elevated style; so much so that the detached reader is apt to feel they have overstepped the bounds of good taste in the direction of affectation and bombast. While often the exposition has an only slightly elevated tone and is pregnant and realistic, we do find in a certain number of passages a passion for the association of ideas which is pushed to an extreme, degenerating into a flight from conceptual reality. Externally, also, many parts are set off from the rest by special titles as more or less independent compositions, and this not without very good reason.