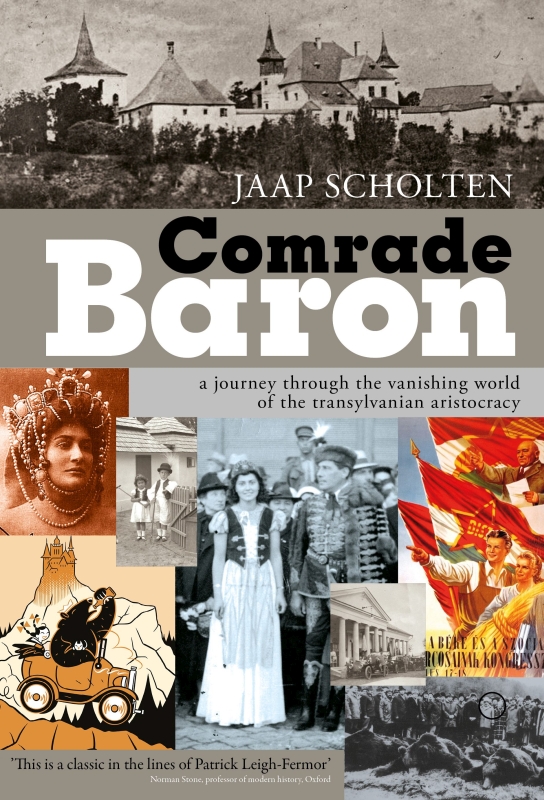

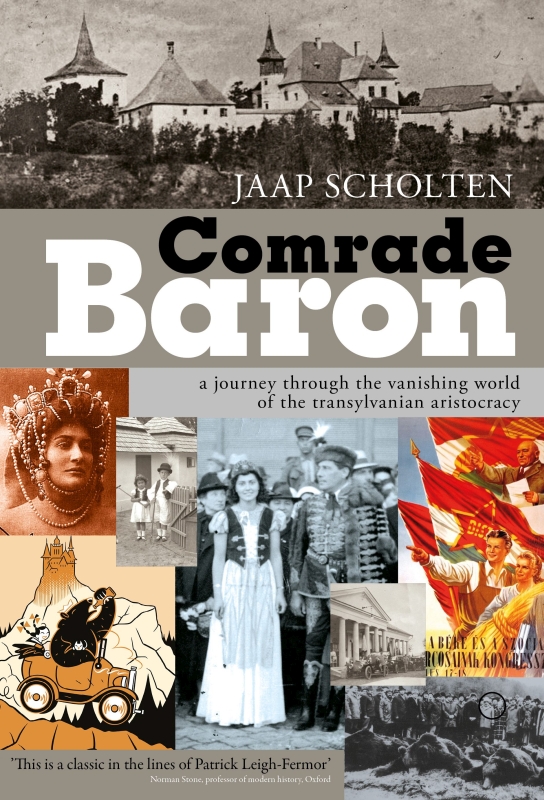

JAAP SCHOLTEN

Comrade

Baron

A journey through the vanishing world of the Transylvanian aristocracy

translated by

Liz Waters

HELENA HISTORY PRESS

Copyright 2016 Jaap Scholten

All rights reserved

Published in the United States by:

Helena History Press LLC

A division of KKL Publications LLC, Reno, Nevada, USA www.helenahistorypress.com

ISBN: 978-1-943596-02-7

Order from:

Central European University Press 11 Ndor utca Budapest, Hungary H-1051

Email:

Support provided the author by:

Fonds Bijzondere Journalistieke Projecten Amsterdam

First Published as Kameraad Baron Een reis door de verdwijnende wereld van de Transsylvaanse aristocratie

by Atlas Contact, Amsterdam 2010.

Translator: Liz Waters

Graphic Design:

Sebastian Stachowski and Jaap Scholten

Printed in Hungary by Prime Rate Kft.

Budapest First Worldwide English Edition

For my sons

Zeeger, Jozsi and Otto

'Memory must be a road not only

to the past but also to the future.'

Ana Blandiana

Contents

Note to the English edition

It's a year before her death and I'm driving in Transylvania, through the hills midway between Sighioara and Braov. I'm going to see an English writer who lives in a remote Saxon village with a very beautiful gypsy girl. I stop at a parking spot on a bend. In the verge lies a mountain of garbage such as you come upon only in countries with an abundance of nature. I walk down the hill along a cart track that leads into the forest and arrive at a gurgling mountain stream. I step among the pebbles and scoop silt with my hands into a plastic bag. I've come to this spot deliberately, for some Transylvanian soil to put on her grave. I know she'll appreciate it.

The next day I fly back from Marosvsrhely to Budapest with the bag of soil in my hand-luggage and at the airport I receive a text telling me that Erzsbet has been admitted to hospital. I hurry home and drive the Land Rover out of Budapest towards the Pilis Mountains. There is something unreal about this. I need to hurry. It's Friday afternoon.

I've bought a bunch of yellow roses, from the flower stall next to the Szamos patisserie. I hesitated; were roses too frivolous for a critically ill 92-year-old? But I chose them all the same, an uneven number, otherwise they would bring bad luck. When the flower seller asked whether I wanted a ribbon around them I glanced at the black ribbon for a second, but no, that would be going too far. I had a feeling that her transfer to a remote hospital might be Erzsbet's last dance, so I opted for yellow roses. She once told me of a love affair when she was twenty-three. The love of her life, I suspect.

'In 1944 Kolozsvr was half depopulated. In the distance you could hear the guns of the advancing Russians and Romanians. But we danced. Csak egy nap a vilg. Just one day in the world. Every day it was played and sung. Maybe we would die tomorrow. My dance partner was a man of forty-four, a baron. He was in the Casino in Kolozsvr night after night, the club of the aristocracy. Only the high nobility could become members of the Casino in Kolozsvr. He had the head of a Roman and the body of an athlete, and he danced like a butterfly.

'"Do you want to marry him?" asked one of my friends. "No, I don't think so. He's a phantom. He's not of this world." He was a mirage. You can't live with a man like that. He was elegant in everything. All the other men had black tailcoats; his was of green velvet. He walked over to me, gave a four-centimetre bow and said, "Your highness." "I think you've mistaken me for someone else," I said. Your highness is how you address a princess. "No, I haven't mistaken you for anyone else." Then we danced. From that moment on we danced only with each other.

'The front came closer. The last ball was that Saturday and when it was over the Casino would close. He asked whether I wanted to go to the ball with him. I went straight to the shop. I pointed to yellow silk: "Five metres of that." And black silk: "Three metres of that." At Dornafalva I made a dress. I wrapped myself in the yellow silk from the top down and fastened it, as far as the knee. From knee to heel I wrapped the black silk. I showed my father. His only comment was, "I imagine your cousins will be less than pleased." In Kolozsvr much was said about that dress, mainly that it was too coquettish. I danced with him until dawn, until the gypsies went home. He said, "Don't look at me, I have tears in my eyes. This is our last dance. Farewell."

When I woke there was a bunch of yellow roses outside the door to my room in Kolozsvr, tied with a black ribbon.'

In the midst of nature, a number of old buildings are set against a hill, concrete barracks in an arcadian landscape. The terrain is surrounded by a high fence. The gatekeeper lets me in. It's unclear whether this is a mental asylum, an old folks' home or a hospital. I can see no staff, only the man at the gate. The tall grass is flowering. A concrete ping-pong table, crumbling with age, is the only form of distraction in the middle of the barracks. The people walking in the overgrown garden are noticeably disturbed. Between the spruce trees I spot a white coat and go after it in the hope that the doctor or nurse can tell me in which building I will find Erzsbet. With an outstretched arm and a fixed stare he walks towards me, pyjama trousers sticking out from under the white coat, and asks if I have forty forint. After a brief search I find the right building, a four-storey concrete colossus.

Inside, a mild smell of faeces hangs in the air, more penetrating at certain rooms with little old ladies in them. The building looks as if the staff have fled an advancing army. The rooms are unlit, the corridors deserted apart from the occasional body parked in a chair or on a trolley. I find one nurse in a dark office, who tells me I need the first floor.

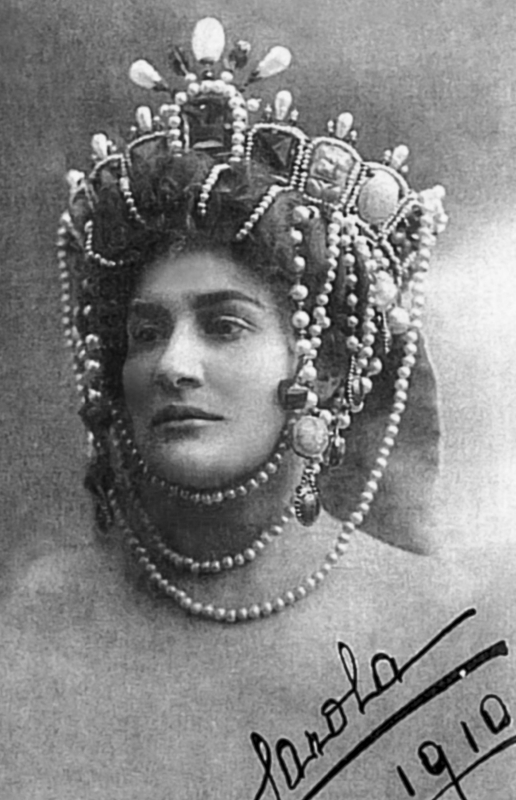

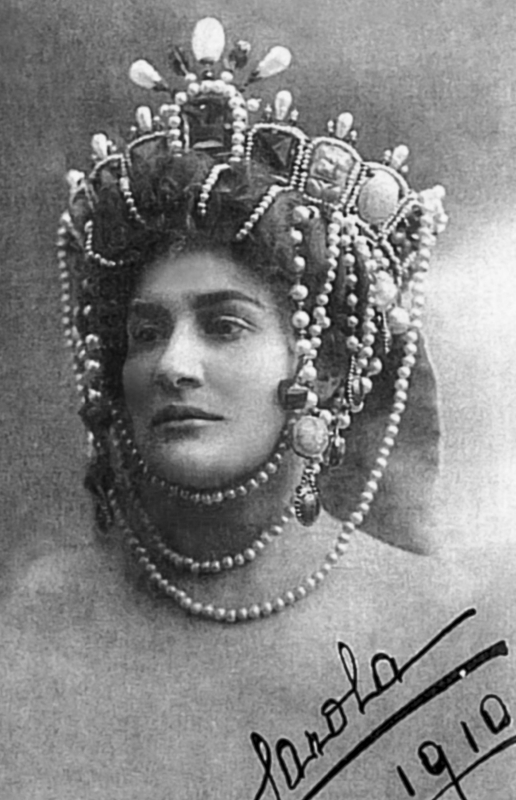

Erzsbet is lying in a room with three very elderly women. She looks dreadful. I barely recognize her. Violet eyes, the colour of a newborn bird. Thin white hair. In the bedside cabinet is a stack of nappies - an indispensable resource in understaffed hospitals.

This is the woman I have interviewed at least fifteen times, the lady who became the central character of this book, a countess born in 'the most beautiful castle in Transylvania' who earned a living as a charlady, painter and editor. She has become very dear to me. She's been extremely generous. The more I saw of her the more she told me, eventually revealing the humiliations and the pain, how in the 1950s she was taken by the secret police to the detached houses of Rzsadomb in Budapest's 2nd district, where she was interrogated and tortured.

'The AVO harassed me for four years. Every night. They threatened to take my child away from me. Occasionally they fetched me for a night-time interrogation. They would drive me to a villa in the 2nd district. They put me under pressure. They wanted me to hide gold coins in the chairs or under the carpets at the homes of other aristocrats, so that they could be arrested. They demanded I tell them who still had money or jewellery. I never said a word.' On one occasion the AVO broke her fingers, another time her toes. In the early morning she was thrown out of a car in a suburb of Budapest and had to make her own way home. 'Everything you experience in life is interesting. How the body deals with it is interesting.'

Next page