R IVERHEAD B OOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2019 by Janny Scott

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Photograph credits appear on .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Scott, Janny, author.

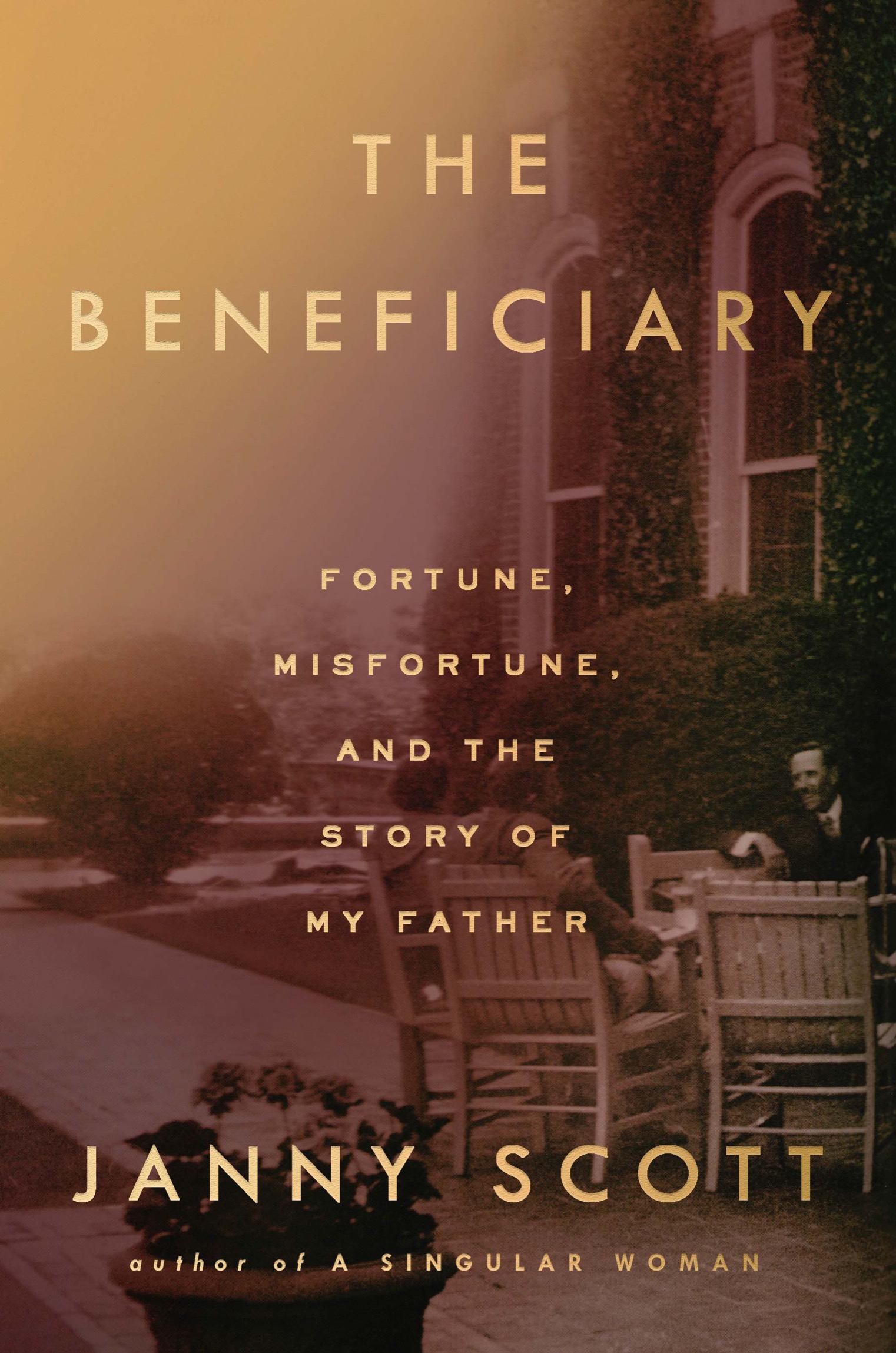

Title: The beneficiary : fortune, misfortune, and the story of my father / Janny Scott.

Description: New York : Riverhead Books, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018029516 (print) | LCCN 2018052501 (ebook) | ISBN 9780698195752 (E-book) | ISBN 9781594634192 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Scott, Robert Montgomery, 19292005. | Scott, JannyFamily. | Philadelphia (Pa.)Biography.

Classification: LCC F158.54.S36 (ebook) | LCC F158.54.S36 S36 2019 (print) | DDC 974.8/11043092 [B] dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018029516

Cover design: Grace Han

Cover photograph: Courtesy of the MontgomeryScottWheeler family collection, privately held at Ardrossan, the Montgomery familys home in Radnor Township

Version_1

For Mia and Owen

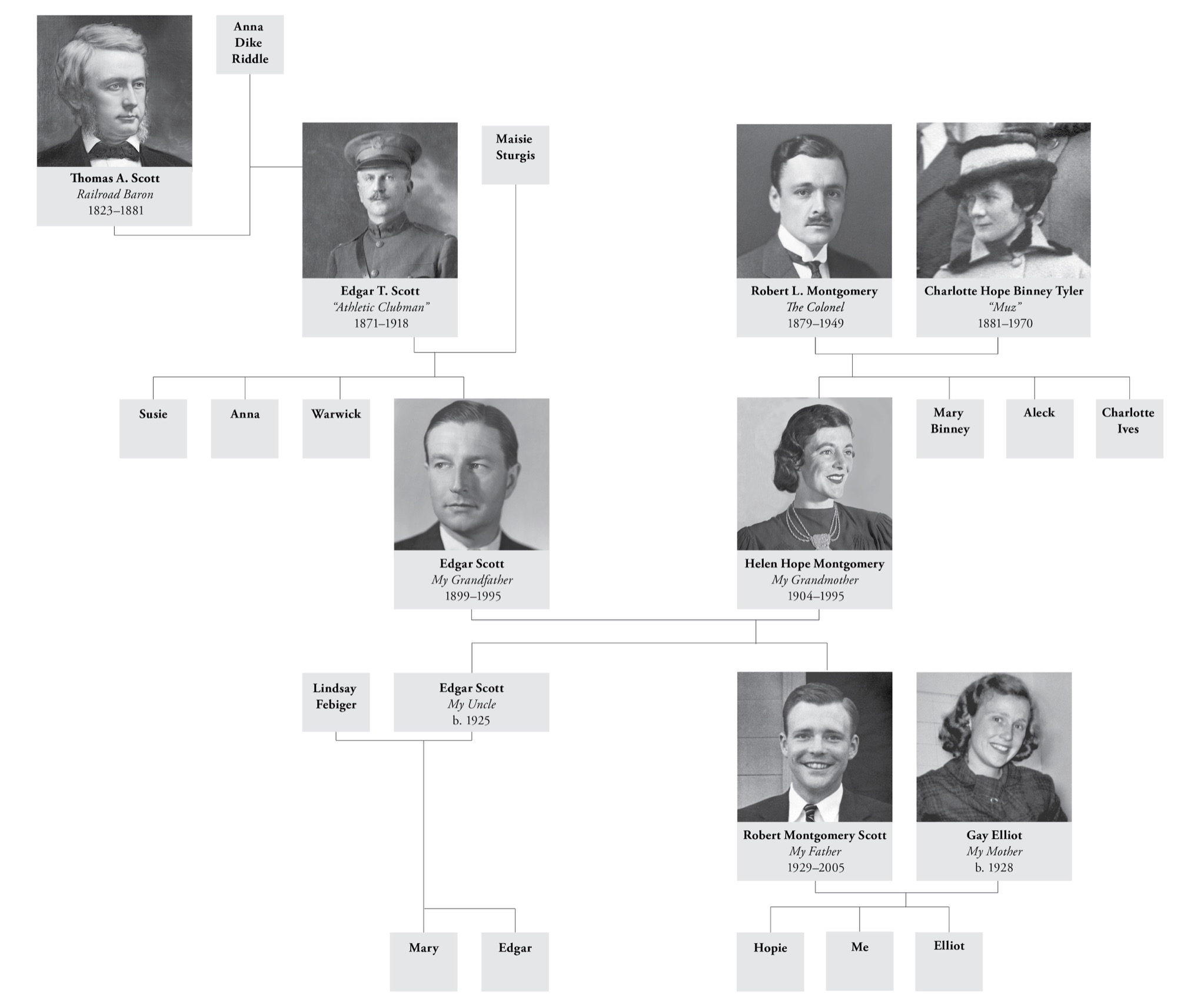

A Partial Family Tree

There are two parts of meyes, he had been moved to go on. One is made up of the history, the doings, the marriages, the crimes, the follies, the boundless btises of other peopleespecially of their infamous waste of money that might have come to me. Those things are writtenliterally in rows of volumes, in libraries; are as public as theyre abominable. Everybody can get at them, and youve, both of you, wonderfully looked them in the face. But theres another part, very much smaller doubtless, which, such as it is, represents my single self, the unknown, unimportantunimportant save to youpersonal quantity. About this youve found out nothing.

Luckily, my dear, the girl had bravely said; for what then would become, please, of the promised occupation of my future?

Henry James, The Golden Bowl

Chapter One

On a rainy October afternoon in the early years of the twenty-first century, in the prosperous suburbs that roll west from Philadelphia along what was once the Pennsylvania Railroads main line, a crowd gathered at a church, founded three hundred years earlier as an outpost of the Church of England, to mark the untimely passing of the Duke of Villanova. After the service, in which men mumbling incantations dispensed wafers and wine to congregants lined up before the altar, the crowd spilled from the church, dispersed into cars, and bolted for what many must have anticipated would be the Dukes final bash. Vehicles lurched out of the parking lot, accelerating past the mossy churchyard where his ashes lay freshly deposited beneath a blanket of mud. A conga line of SUVs, hybrids, and limousines soon stretched the entire two-mile route to the reception, which, as everyone in that crowd could have guessed, was to take place in the fifty-room hilltop pile that had served as headquarters for the deceaseds family for ninety-one years. The house had acquired a certain mystique in those parts, not merely for the hundreds of acres of rolling fields and woods over which it still presided at a time when single acres in the area were going for a quarter of a million dollars, but for the predilection of its owners, through three long-lived generations, for carrying on in a vivid, anachronistic style, and for throwing some unforgettable parties.

The route from the church that afternoon wound past the traces of a vanishing past, when fortunes made from sugar refining, liquor distilling, and the condensing of soup had made possible the creation, a century earlier, of dozens of country estates modeled unapologetically on those of the British. Most had flourished for a generation, maybe two, before taxation, the Depression, and dynastic vicissitudes did them in. Manor houses, baronial in scale, were hastily demolished or unloaded onto colleges and schools. Some survived as the stately centerpieces of retirement communities, adrift in an archipelago of villas. Where lawns had once spread, present-day palazzi sprouted. Pharm Belt millionaires, flush with profits from the sale of antidepressants and statins, poured in. As the old road from the church dipped and wove, the procession rumbled past home-security-system signs, duck ponds, and the occasional vestigial stone gatepost bearing the name of one more family in the latter stages of being forgotten.

At the top of a hill a mile from the church, cars climbed to a T intersection and slowed to a stop, their drivers idling for a moment to peer down the other side of the hill for oncoming traffic. Beyond the road, a panorama spread before them like the backdrop of some enormous outdoor stage at opening curtain. To the left of the road, a hayfield plunged and majestically rose, its contours undulating like ocean swells. Beyond it, a pasture spilled toward the horizon; another, beyond that. To the right of the road, a cornfield sloped downhill toward the dark margin of a wood. A farm road arced through the rows of khaki stubble. No driver that afternoon, pausing, could have missed the sightthe northeast corner of the largest piece of open land left in the township, vast enough in its golden era to have spanned four unincorporated communities. Each car idled for a moment, then pressed on, accelerating across the opposite lane onto a long, straight road that ran alongside a stone wall stretching as far as one could see. Near the walls midpoint, a high, wrought-iron gate interrupted the ribbon of gray stone. Cars slowed, turned, and glided through the entrance to the place.

There was no dukedom, of course. The title was a private joke, deployed by his wife and children in moments of exasperation with flights of grandiosity now long forgotten. My sister and brother and I used it mockingly but not without affection; wed never have let it slip in his presence. Hed been cast in a role in life, which he seemed to have embraced out of duty, filial devotion, family pride. That hed played the part to acclaim was evident in the funeral turnout, which included people from the dozen and a half cultural and civic institutions in and around Philadelphia that hed servedall listed on the back page of the program. There were museum curators, philanthropists, smaller donors, musicians, newspaper reporters, men and women whod spent their lives working in the houses and barns of his grandparents and parents. There were a few rubberneckers, too. He wouldnt have minded; hed have been flattered. In his later years, hed taken to sending us copies of articles about himself clipped from city magazines and local newspapers, which never tired of him as a subject. For all their well-intentioned fawning, it seemed to me, journalists rarely got him right. Hed mail out copies anyway, with a note on a Post-it affixed, simultaneously self-mocking and pleased. He knew as well as we did, maybe better, what the scribblers missed. Hed been catching sight of himself for years, as though brought up short by his reflection in a store window. To the extent that his performance was sometimes over the top, hed never quite managed to look the other way.