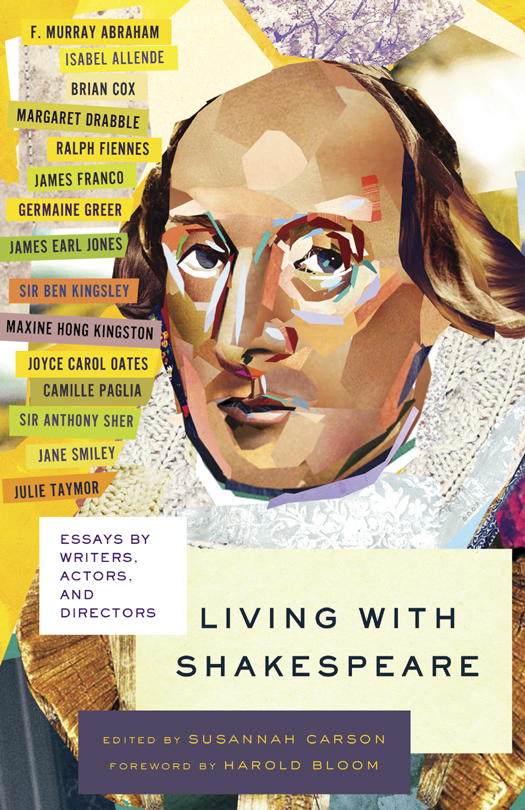

Susannah Carson

LIVING WITH

SHAKESPEARE

Susannah Carson is an American author, editor, and academic. She received her PhD from Yale after earning graduate degrees at Paris III, La Sorbonne-Nouvelle, and Lyon II, LUniversit des Lumires. A Truth Universally Acknowledged: 33 Great Writers on Why We Read Jane Austen was her first edited volume of literary essays. Her work has appeared in newspapers, magazines, collections, and scholarly publications.

ALSO EDITED BY SUSANNAH CARSON

A Truth Universally Acknowledged:

33 Great Writers on Why We Read Jane Austen

A VINTAGE BOOKS ORIGINAL, APRIL 2013

Introduction and compilation copyright 2013 by

Susannah Carson

Foreword copyright 2013 by Harold Bloom

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

constitutes an extension of this copyright page.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Living with Shakespeare: Essays by Writers, Actors, and Directors / Edited by Susannah Carson; Foreword by Harold Bloom.

pages cm

1. Shakespeare, William, 15641616Appreciation. 2. Shakespeare, William, 15641616Influence. I. Carson, Susannah, editor of compilation.

PR2976.L56 2013

822.33dc23 2012039745

Ebook ISBN9780307743404

Cover design and illustration by Ben Wiseman

www.vintagebooks.com

v3.1_r2

CONTENTS

Harold Bloom

FOREWORD

Who Else Is There?

In my long career as a teacher, I have found that students, interviewers, and fellow readers keep asking me, Why Shakespeare? It seems a question as necessary to ask as it is impossible to answer, unless you respond, Who else is there? Who but Shakespeare has influenced so many creative intellects? The genealogy includes Milton, Austen, Dickens, Keats, and Emily Dickinson, and many of the strongest writers of our own generation. Who besides Shakespeare has perfected expressions of experience, and broadened and defined the horizons of human possibility? He has given us, through thirty-seven plays, 154 sonnets, and four longer poems, a secular religion.

His is the most capacious of consciousnesses. He comprehends and apprehends realities that are available to us but beyond our ken until he manifests them.

If you run any mode of criticism, whether historicismold or newor analytical, through Shakespeare, you find it is Shakespeare who illuminates your mode of thinking and not the other way around. His is an electrical field. Anything entering it will light up, but Shakespeare powers the illumination.

There is no God but God, and his name is William Shakespeare. Yahweh is not God. William Shakespeare is God. Heinrich Heine said, There is a God, and his name is Aristophanes. On Heines model, I again remark: there is a God, there is no God but God, and his name is William Shakespeare.

Shakespeare did not set out to create a religion, or to define us. We can never know his motivespresumably to fill seats, write good parts for his actors, stay out of the sight of Walsingham, Elizabeths Chief of the Secret Service, and so avoid the fate of Thomas Kyd, who was tortured, and Christopher Marlowe, who was stabbed to death. In the plays, we find traces of Shakespeares evolution as an artist. He swerves from the influence of Ovid, Chaucer, and Marlowe, and discovers that the only opponent worthy of agon is the writer of his own earlier plays. Not Shakespeare as man, but Shakespeare as playwright was the source of his own continued artistic struggle to break free of self-overdetermination.

Paul Valry, great theoretician of influence, said we must learn to speak of the influence of a mind upon itself, a very rich insight which I have adapted to my own understanding of Shakespeare. After a large book on Shakespeare called The Invention of the Human and a shorter one devoted to Hamlet called Poem Unlimited, I explored the influence of Shakespeares mind upon itself in The Anatomy of Influence, which provides some radically new readings of the elliptical qualities in Hamlet, in The Tempest, and of Edgar in King Lear. The only significant influence on Shakespeare, in the end, was Shakespeare himself. Increasingly in his work, what he leaves out becomes much more important than what he puts in, and so he takes literature beyond its limits. He transforms himself, a victory for art, and yet his own position as poet and as self-precursor resulted in an internalization of the conflict and an unresolvable ambivalence.

The result is a panoply of characters who possess inner lives so very intricate that, although they are finite on the page, to us they nevertheless remain infinite in faculty and endless to meditation. The more elliptical the renderings, the more complex, illusory, and transformative the result. Shakespeare invented the depiction of inwardness in imaginative fiction, and with these characters he shows us how to overhear ourselves think and, by so doing, become richer, more complex, and more sensitive human beings. We learn about ourselves in these plays, and at the same time we enter their worlds to overcome our loneliness. These are our friends, our lovers, our enemies, our parents, our children, and the characters we encounter only briefly in the course of our daily lives.

Ralph Waldo Emerson said that Shakespeare wrote the text of modern life, which means that we are all of us, each in turn, a kind of amalgam of various Shakespearean roles, though I would prefer to call them people. Shakespeare is people, and I write about them not only as roles to be performed, but as more real than you and I. If this is an eccentricity, at least it is a useful one for many actors, and for readers who look to literature for more than confirmation of their own critical agendas.

Old Bloom likes to identify with Sir John Falstaff, but another part of him secretly and inwardly identifies with the Black Prince of Denmark, and another part, rather yearningly, doesnt identify with, but wishes he were on warm terms with, Cleopatra of Egypt. Many years ago, in London, I saw a production of Macbeth with Michael Redgrave as the hero, and the marvelously fierce, sexually intense actress Ann Todd playing Lady Macbeth. When she cried out Unsex me here! Miss Todd grabbed herself in the crucial area and doubled over. Many men in the audience were highly activated.

My favorite fantasy is that Falstaff did not allow himself to be done in by his murderous adopted son, the dreadful Prince Hal, and instead Shakespeare let him wander off to the Forest of Arden. There he sat on one end of a log, with the beautiful Rosalind on the other, and the two matched wits. Orson Welles had a fantasy in which he remarked that Hamlet did not go back to Elsinore but voyaged on to England, where he eliminated poor Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, stayed on, grew old and fat, and became Sir John Falstaff. Welles played a splendid Falstaff in the movie Chimes at Midnight, with Jeanne Moreau as Mistress Quickly.

We are used to characters breaking loose from Shakespeare. You cannot confine these figures to their own plays. They become instances of what was said of Spensers