Table of Contents

Guide

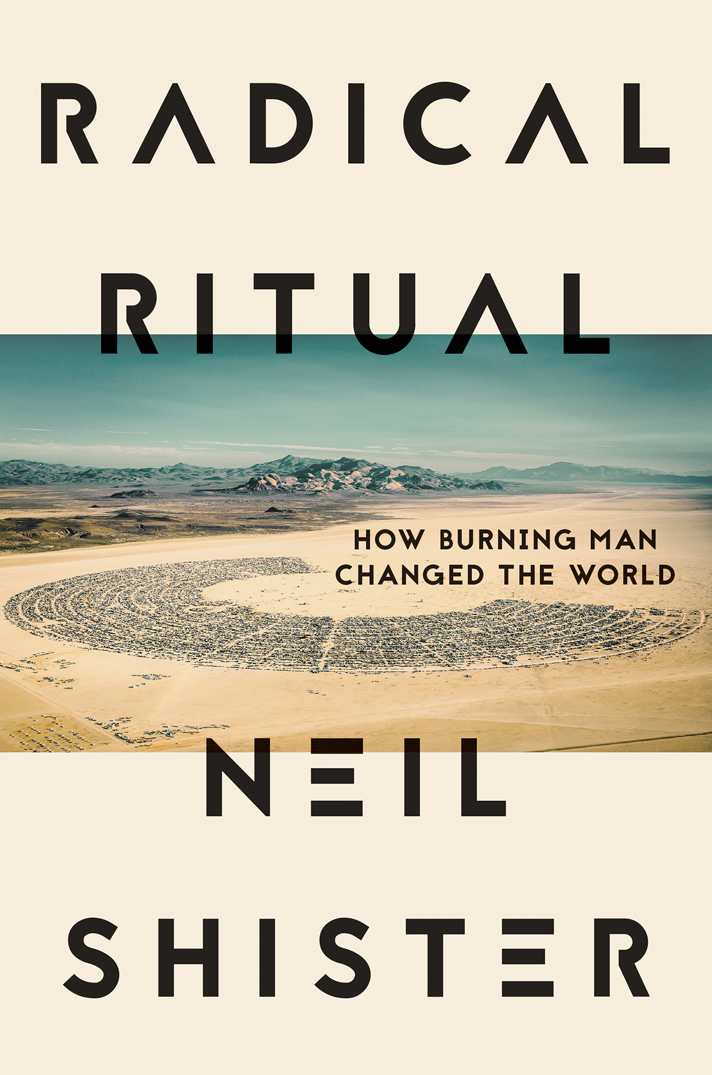

Radical Ritual

Copyright 2019 by Neil Shister

First hardcover edition: 2019

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Shister, Neil, author.

Title: Radical ritual : how burning man changed the world / Neil Shister.

Description: First hardcover edition. | Berkeley, California : Counterpoint, 2019. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018051326 | ISBN 9781640092198

Subjects: LCSH: Burning Man (Festival) | Burning Man (Festival)Interviews. | Art festivalsSocial aspectsNevadaBlack Rock Desert. | Art festivalsPolitical aspectsNevadaBlack Rock Desert. | Shister, Neil.

Classification: LCC NX510.N48 S55 2019 | DDC 700.74dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018051326

Jacket design by Sarah Brody

Book design by Jordan Koluch

COUNTERPOINT

2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Printed in the United States of America

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Cait, who gets me to all places, including Burning Man

Collaboration is the soul of culture, but the system divides people.

LARRY HARVEY

CONTENTS

The hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.

JOSEPH CAMPBELL, The Hero with a Thousand Faces

The essential thing to understand about the whole Burning Man phenomenon is that nobody saw it coming.

Not even your looniest, acid-addled Haight-Ashbury whack job in the wildest of hallucinations could have foreseen in 1986 the chain of events stemming from an impromptu bonfire on a San Francisco beach. It would lead three decades later to official Washington, where the august Smithsonian Institution devoted the entire Renwick Galleryhoused in Americas oldest art museum, a few steps from the White Houseto an exhibition that traced back to that bonfire.

The person who least anticipated the magnitude of what was starting was the man who began it all. Larry Harvey, with a close friend and their young sons, lit that first fire in part to heal his broken heart. It was an act of self-medication. From that unlikely spark, a full-blown culture has taken form. Hundreds of thousands of celebrants have partaken of it in the Nevada desert over the years, close to a million people if you count sister events all over the world. A full-fledged, multi-million-dollar apparatus exists to spread that culture. The annual celebration, unnamed in the beginning, is now a global brand. But, to repeat, nobody foresaw any of this.

Were we back in biblical days, this tale might mark the start of a religion. One can imagine, say, somewhere in the Sinai wilderness, a crew like Harvey and his tiny cadre of fellow Founders. A visionary prophet with a scruffy band of acolytes, evangelizing a message of salvation that mesmerized growing multitudes.

Indeed, Harvey et al. could be regarded as another installment in a long list of American nonconformists who rewrote the scriptures as they crossed the continent. Maybe the Puritan elders could keep their progeny toeing the line back in Boston, but the kids shucked off those theological shackles when they hit the frontier. Enthusiasm consistently trumped piety in the great trek westward. When they finally reached the Pacific, with nowhere farther to go, what started as radical nonconformity gradually went mainstream as it ricocheted back east. To that point, some might compare the Renwick exhibitionthe symbolic moment when power cedes respectability to outlaw renegades from the outbackto when the Roman emperor Constantine gave the official seal of approval to Christianity.

That, however, would be a wrong reading of the intent of the Founders. If religion is about ancestral reverence and supernatural awe, then Burning Man is about human agency in the moment. It is postmodern rather than theological. In 1966, as Larry Harvey was coming of age, the cover of Time magazine wondered aloud, Is God Dead? To dare ask such a question, forget about the answer, called into doubt civilizations most venerated certainty. Paradigms that had held society intactsecular and theologicalwere losing their grip. The Founders were hip to this. But they werent out to start a religion. Their intention wasnt to allay anxiety by invoking some new supernatural entity. Just the opposite. The whole raison dtre of Burning Man was to sow doubt.

In the Burning Man cosmology, all truth is relative and all narratives equally credible. The culture posits no eschatological destination. Assumptions are never to be trusted on authority, only tested through experience. The sole orthodoxy is that there is no deference owed orthodoxy. Destiny for good or ill is the product of human acts. Thus, and herein resides the supreme tenet, people are capable of creating... anything.

The origins of Burning Man were a result of a specific place and moment. San Francisco in the mid-1980s was poised on a historical cusp. The magical mystery tour of the counterculture Sixties was about to combine with the digital wizardry taking form down the peninsula in Silicon Valley. These two vectors slammed into each other like particles in a cyclotron, fusing a new element from soul and science. One primal expression of it would emerge as Burning Man.

The Bay Areaport of call to whalers and gold rushers, communist longshoremen and vanguard gay activistsbreeds more eccentricity pound-for-pound than anywhere else in America. Personal re-invention is in the water. Call it liberation or license, social rules are pliant here. Maybe such broad-mindedness is a natural adaptation, the response to a geological landscape that can split open without warning. Living on a fault line, as one local observer understood, is no easy business. Toleration, a mere virtue elsewhere, is more a strategy for mutual survival. That, along with natural beauty, a temperate climate, and nearby vineyards, makes for an existential wonderland. It is and has everything, wrote Dylan Thomas. And all the people are open and friendly.

By 1986, as Harvey and his pal Jerry James were hammering together scrap wood for the first Burn, the last wave of the Sixties counterculture that crested in San Francisco had pretty much ebbed. The ardor of insurrection was spent. The rising generation, who grew up with Ronald Reagan, didnt want to overthrow the system, they wanted to own it. Still, among the elders who had known the glory days, vestiges of rebellion lingered.

Meanwhile, south of the city in towns like Mountain View and Cupertino, a new swell was building. The digital epoch was poised to kick into overdrive. In 1986, IBM introduced the original laptop (weighing twelve pounds, it was a commercial dud). Detroits car industry, linchpin of Americas industrial might, was aging out but didnt yet know it. The days of slow-moving technology, stable markets, and mass production processes that once allowed our industries to thrive in a sheltered environment have long since passed, Harold Shapiro, president of the University of Michigan, warned auto execs in his home state that year. They werent listening. Who wants to hear their days are numbered? The electrical engineers and computer scientists at Stanford, however, got it. As did the smart venture capital money along Sand Hill Road in Palo Alto that was laying down tech bets.

Next page