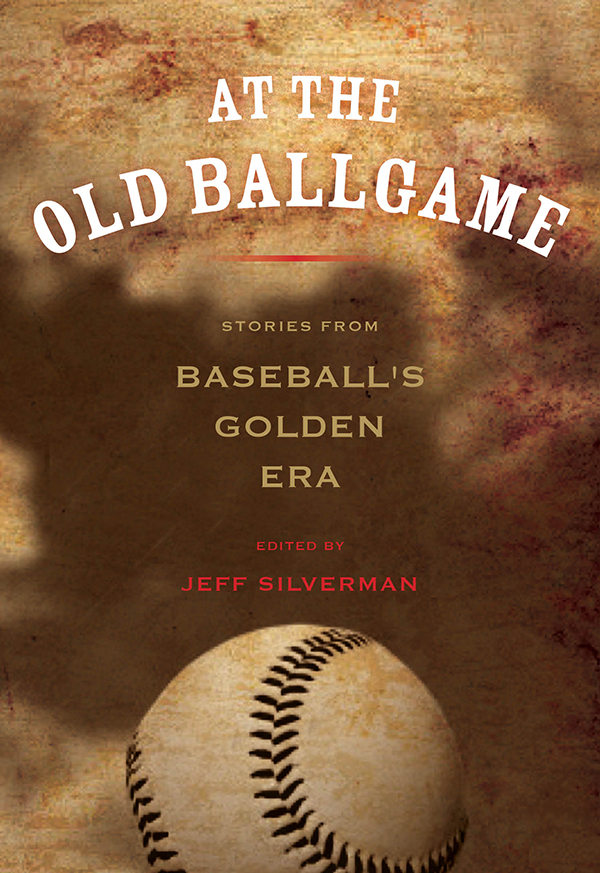

A T THE O LD B ALLGAME

A T THE O LD B ALLGAME

Stories from Baseballs Golden Era

E DITED BY J EFF S ILVERMAN

LYONS PRESS

Guilford, Connecticut

An imprint of Globe Pequot Press

Copyright 2003, 2014 by Morris Book Publishing, LLC

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, PO Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

Lyons Press is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

Project editor: Staci Zacharski

Layout artist: Sue Murray

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

E-ISBN 978-1-4930-0721-9

To the Men of Claw...

Rarae aves, most of them...

C ONTENTS

Why Base Ball Has Become Our National Game

by Albert G. Spalding

The Model Base Ball Player

by Henry Chadwick

Casey at the Bat

by Ernest Lawrence Thayer

Caseys Revenge

by Grantland Rice

The Color Line

by Sol White

A Whale of a Pastime

by Brig. Gen. Frederick Funston

The Rubes Honeymoon

by Zane Grey

How I Pitched the First Curve

by Candy Cummings

Discovering Cy Young

by Alfred H. Spink

Varsity Frank

by Burt L. Standish

Baseball Joes Winning Throw

by Lester Chadwick

Mr. Dooley on Baseball

by Finley Peter Dunne

Jinxes and What They Mean to a Ball-Player

by Christy Mathewson

One Down, 713 to Go

by Damon Runyon

How I Lost the 1915 World Series

by Grover Cleveland Alexander

The Crab

by Gerald Beaumont

My Roomy

by Ring Lardner

The Longest Game

by Ralph D. Blanpied

Fullerton Says Seven Members of the White Sox Will Be Missing Next Spring

by High S. Fullerton

His Own Stuff

by Charles E. Van Loan

The Pitcher and the Plutocrat

by P.G. Wodehouse

The Slide of Paul Revere

by Grantland Rice

I NTRODUCTION

So, whats the essential quality that turns a baseball story into a classic baseball story? Lets touch base for a moment with Americas other national pastime: the movies.

Every year, the American Film Institute hands out a Life Achievement Award to an honoree whose workso the AFIs Solons assure ushas stood, or will stand, the test of time. What a nice soundthe test of timeand what an exacting criterion. To satisfy it, the work must certainly have legslike Cobb and Brock and Ricky Henderson; personalitylike Ruth and Stengel; powerlike Big Mac and the Big Train; craftlike Koufax and Mathewson; gracelike DiMaggio and Williams; couragelike Robinson and Aaron; durabilitylike Ripken and Ryan; and characterlike Clemente and Gehrig. As commendable, individually, as these qualities certainly are, they need more than themselves alone to pass the test; each needs at least a touch of the other. To be classic, in short, is a tall order.

Each of the twenty-two talesthe fictions and the factsthat make up At the Old Ballgame has stood this test of time. They all satisfy the most readily measured thresholdlegswith ease. The baby in the groupGerald Beaumonts The Crabwas first published in 1921, and if we keep the comparison to the movies in play, that puts it squarely in the silent era. Indeed, the majority of the selections that follow gave voice to a game before the movies realized they had any voice at all. They are tales from a time when Cobb and Speaker were hitting .400, when Johnson and Matty (a contributor here, at least in name; his observations about play superstitions were actually penned by sportswriter John Wheeler) were moving em down, and when artists like Chaplin and Keaton and D. W. Griffith were taking cuts and making cuts, inventing, as they went along, the grammar of the movies frame by frame.

It was a good time for invention, those days, and in their own way, writers like Ring Lardner, Damon Runyon, Grantland Rice, Zane Grey (yes, that Zane Grey, a helluva college outfielder by the way), Charles Van Loan, and even P.G. Wodehouse (more associated with a small, dimpled ball than one of horsehide stitched together) were also busy making up the language and syntax of the baseball story as they went along. With their pens and their typewriters, they would teach us a new way of seeing and experiencing Americas game; reaching into its heart, they pulled out what would become the ever more sophisticated language of baseball on the page.

Theres magic in that accomplishment to be sure, and the best way to fall under its spell is to continue reading what they batted out. Granted, some of their words and phrases and idioms feel datedwhat doesnt after a century or so of servicebut that hardly matters because what they discovered about the game and its hold over usfans and players alikeis as fresh and excited as a bushers face the first time he puts his Major League polyesters on. Keaton and Chaplin are still funny; so are Lardner and Wodehouse. Theyre old, sure, but their bones dont creek. What theyve set down remains energetic and bright, keenly observed and keenly wrought. All these decades later, the words continue to tingle.

Of course, when you understand human nature and baseball natureas these writers didthe work doesnt really age, just the paper its printed on. New generations may find more dazzling or sophisticated ways to say things, as new generations of filmmakers keep upping the ante on their special effects, but is what theyre revealing to us about who we are any sharper, clearer, more incisive or passionate? A home run is a home run whenever its hit.

Let me suggest one more connection that ties the early days of baseball writing to the early days of motion pictures: Theres a history, memory and sheer enjoyment thats lost when we fail to preserve and keep contact with the legacy handed down to us.

Twenty years ago, when I was a novice screenwriter, I became friends with an older writer-director named Richard Brooks. In the late 1950s, he created one of the most memorable on-screen fires in his classicI use that word with no reservations at alladaptation of Elmer Gantry . Since the blazing tabernacle scene climaxing the movie would be shot indoors on a soundstage, every inch of the set had been treated with heavy fire retardent before the cameras rolled. Starting a fire 20,000 leagues under the sea would have been a snap by comparison.

Naturally, Brooks couldnt get the flames to go, so he asked the fire marshall on set what to do. The answer stunned the filmmaker. The fire marshall told him to raid the studio vault, pull out as many old cans of the silent moves stored inside as he could, then coat the set with their contents. Are you mad? Brooks, a noted rager, raged. Thats the heritage of our craft. The fire marshall shook his head sadly. He knew that. But he also knew that no one had put much thought into how best to preserve it. When Brooks opened those precious cans of ancient history, what he mostly found was highly combustible silver nitrate powder; the old film had decomposed as badly as a forgotten corpse. Brooks spread it around the set, and, as the past exploded around him, a remarkable movie moment rose from its ash. Still what was lost in those cans remains lost forever.

Thankfully, baseballs past has been better preserved in archives and libraries from coast to coast. But preserving the past isnt enough. These stories arent just museum pieces; they live with the spirits of their creators and the spirit of the game. Now and again, they need to come out, stretch their muscles, and show off just how good they are. For them. And for us.