Contents

Guide

Why did you write the book?

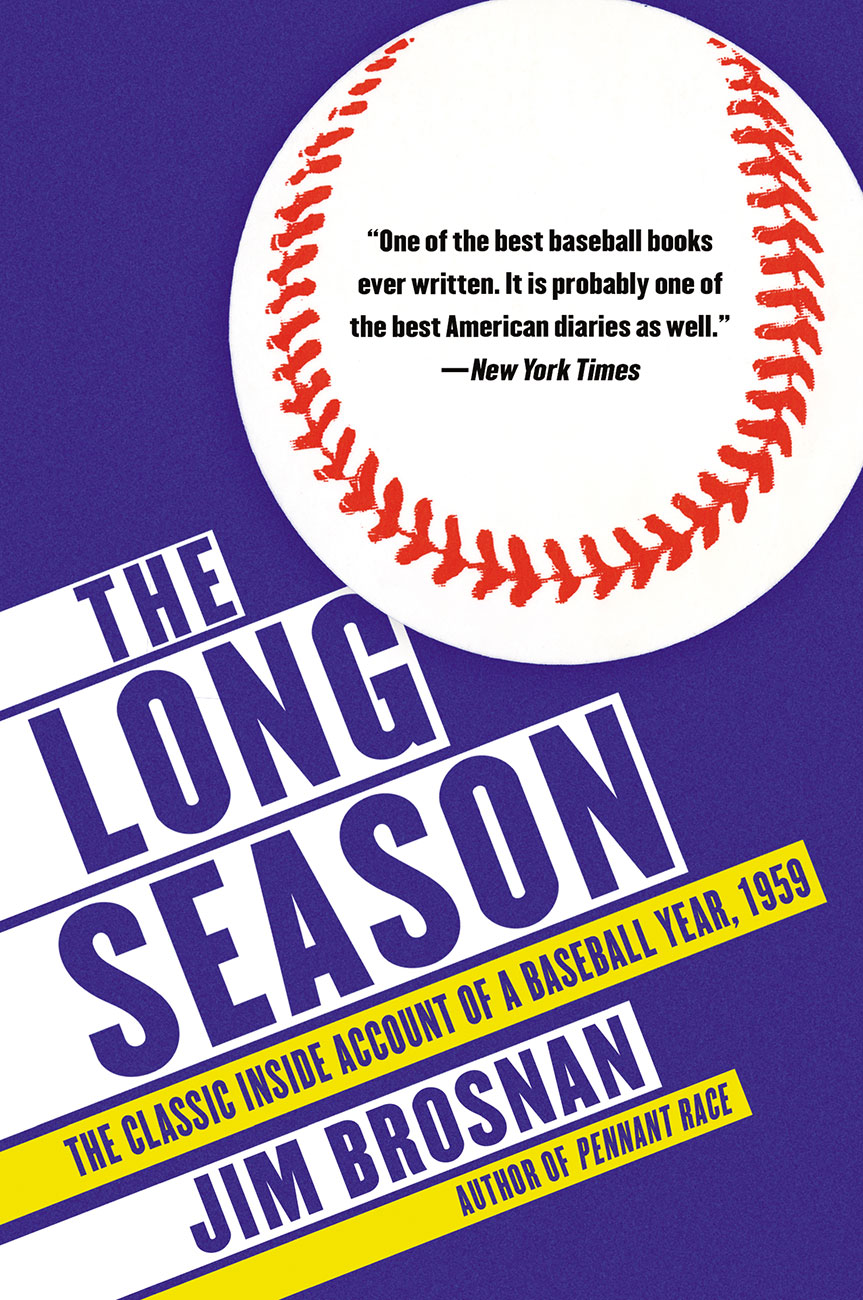

That is the question Ive been asked countless times by baseball fans ever since The Long Season was first published in 1960. The new millennium seems a good time for an answer.

At the age of eleven I had an epiphany. Rare for a subteen, but manifestly possible. It happened at the Westwood Public Library in the Western Hills suburb of Cincinnati. All those books on all those shelves! What joy I got from digging into that small literary treasure!

WHAT A KICK YOUD GET IF YOUR NAME WAS ON ONE OF THOSE BOOKS! It was the voice of that cunning imp, Ambition, sowing a seed that would grow for twenty years.

My mother wanted me to be a concert pianist. My two maiden aunts wanted me to be a priest. I had neither talent for the former nor a vocation for the latter.

At Cincinnati Elder, the local parochial high school, I learned to read Latin, play the trombone, and write essays, one of which pleased the history teacher no end but failed to impress my father, who wanted to know what I was going to do for a living.

The only useful thing I could do, apparently, was throw a baseball faster than the average sixteen-year-old. Pitching for Bentley Post, a perennial powerhouse among American Legion teams, gave me a chance to be seen during the summer by major league scouts in four states.

The only one interested was Tony Lucadello of the Chicago Cubs. He had seen me pitch shutouts in the regional and sectional tournaments. When he learned that I had already graduated from high school, he offered me a bonus of $2,500 if Id sign a minor league contract.

My diary for 10/24/46 read: Eureka! Manna from Heaven! Merry Xmas to me! Merry Xmas to me!

I should have checked the contract first. It would pay me $125 per month for the four-month season. Even if I won all my games, Id surely lose weight on such paltry pay.

During the next four minor league seasons I won as often as I lostwhich, in the Cubs organization at that time, meant promotion to a higher classification. I was ticketed for Triple-A ball in 1951 when the Selective Service System called my number. Id be in the army for the next two years.

A grizzled, baseball-loving sergeant told me how to play the old army game. Get to know the first sergeant, the supply sergeant, and the mess sergeant. Treat them right and theyll take care of you.

As company mail clerk I made sure to hand deliver their mail twice a day. In return I got the occasional weekend pass, a brand-new winter coat, and all the food I could stuff in my mouth. In two years I put on forty-five pounds.

I had promised myself that Id write a book about my army experiences. Hemingway did it, didnt he? Mailer. James Jones. Irwin Shaw.

The trouble was this: my only army experience worth writing about was my honeymoon. PITCHER MARRIES PITCHER should have been the headline when, on June 23, 1952, Anne Stewart Pitcher married Jim Brosnan, pitcher, in the chapel at Fort Meade, Maryland. She was a freckle-faced Virginia belle, a civilian employee of the army, and she would dance all night at the Civilian Club on the post. She taught me how to dance. Then she taught me how to drive her Chevy convertible. So I had to marry her and promise never to write about that long summer night.

Out of the army and back in the International League, I had a pretty poor season (4 wins, 17 losses) for a pretty poor team in Springfield, Massachusetts. The subsequent invitation to spring training with the Cubs was a pleasant surprise, actually making the team was a shock, and working with pitching coach Howie Pollet proved to be the turning point in my career.

You have a live arm and you change speeds well, he said. You need a breaking ball you can control. Im going to teach you how to throw a slider.

It proved to be the perfect pitch for me. I won eight out of nine decisions in the Texas League, was 17 and 10 in the Pacific Coast League, and was in the Big Show for good in 1956.

Two undistinguished years later I met Bob Boyle of Sports Illustrated. He had heard that my ambition was to write a book about big league baseball. Why dont you write an article for us? he asked. If something significant happensa no-hitter or something like that.

How about if I were traded from the Cubs to the St. Louis Cardinals (for shortstop Alvin Dark)? A mutt for a pedigreed pooch, wrote one reporter. A real steal for the Cubs.

Bah, humbug, I scrooged, and wrote all about it for SI.

Loved it, said Boyle. Why dont you write a book about a whole season?

For the rest of the story, turn to page one.

JIM BROSNAN

Morton Grove, Illinois

November 2001

The following journal is my personal account of the 1959 baseball season... the way I saw it. Certain names, places, and events will be recognized by many readers. Some readers will remember the players, scenes, and action just as I did. In some cases I may have seen things differently. But then no two people can truly say that they see the same thing exactly the same way. Occasionally my viewpoint will prove to be unique; no one else could have seen things just that way. But thats the way I saw it.

Professional baseball in America is not a game, nor can it be called an ordinary business or occupation. Baseball is a pastimea habitwith millions of people... baseball fans. Anyone fanatically attached to baseball considers himself privileged to enter and enjoy the private world of the baseball players. Identification of the fan with the ballplayer goes beyond the playing field, where it traditionally belongs. Many ballplayers (some of whom are not baseball fans) resent an intrusion into their personal lives. The means by which most fans learn what they want to know about the players leaves much to the imagination. The feeble defense with which the players try to prevent the fans from getting to know them too well does little but create confusion. Perhaps that is the way it should be.

The 1959 National League season was my twelfth year as a professional baseball player. It was my fourth season in the major leagues, and, in most respects, a typical year in the average ballplayers career. (With no false modesty I call myself an average professional baseball player.) One season doesnt make a career, of course, but the fan who follows me as I re-create the 1959 season will probably get a little different viewpoint of baseball.

The daily life of the professional baseball player is not really so exciting that it should attract as many adolescent ambitions as it does. Yet, the ballplayers life does have its rewards. In my twelve years in organized baseball Ive played professionally in forty-one of the fifty States, several Caribbean islands, and some Far Eastern countries, including Japan. Had I joined the Navy in 1947 instead of the Chicago Cubs organization I doubt if I would have seen much more of the world. And the pay has been better.

Each and every baseball season has its share of satisfactions and disillusionment, its thrills and despair. Perhaps my account of the 1959 season is less emotional than it actually seemed to others, but then I was born a cynic. The professional life, moreover, grinds and polishes the emotions to a fine, hard corethe professional spirit. Amateur baseball fans may resent, at times, the apparent lack of constant, noisy enthusiasm that is one partbut only a partof athletic spirit. The professional player has more skill and needs no false hustle to do his job. A player who loves his craft and has the patient determination to do the best job he can creates a personal efficiency that is as much a pleasure to watch as it is a help in winning ball games. Running full speed with his mouth open does not always contribute to a players success. The professional stores up, treasures that winning spirit, for there are many long days in the baseball year.