Copyright 2021 by Lew Freedman

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Sports Publishing,

307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Sports Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Sports Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Sports Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.sportspubbooks.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

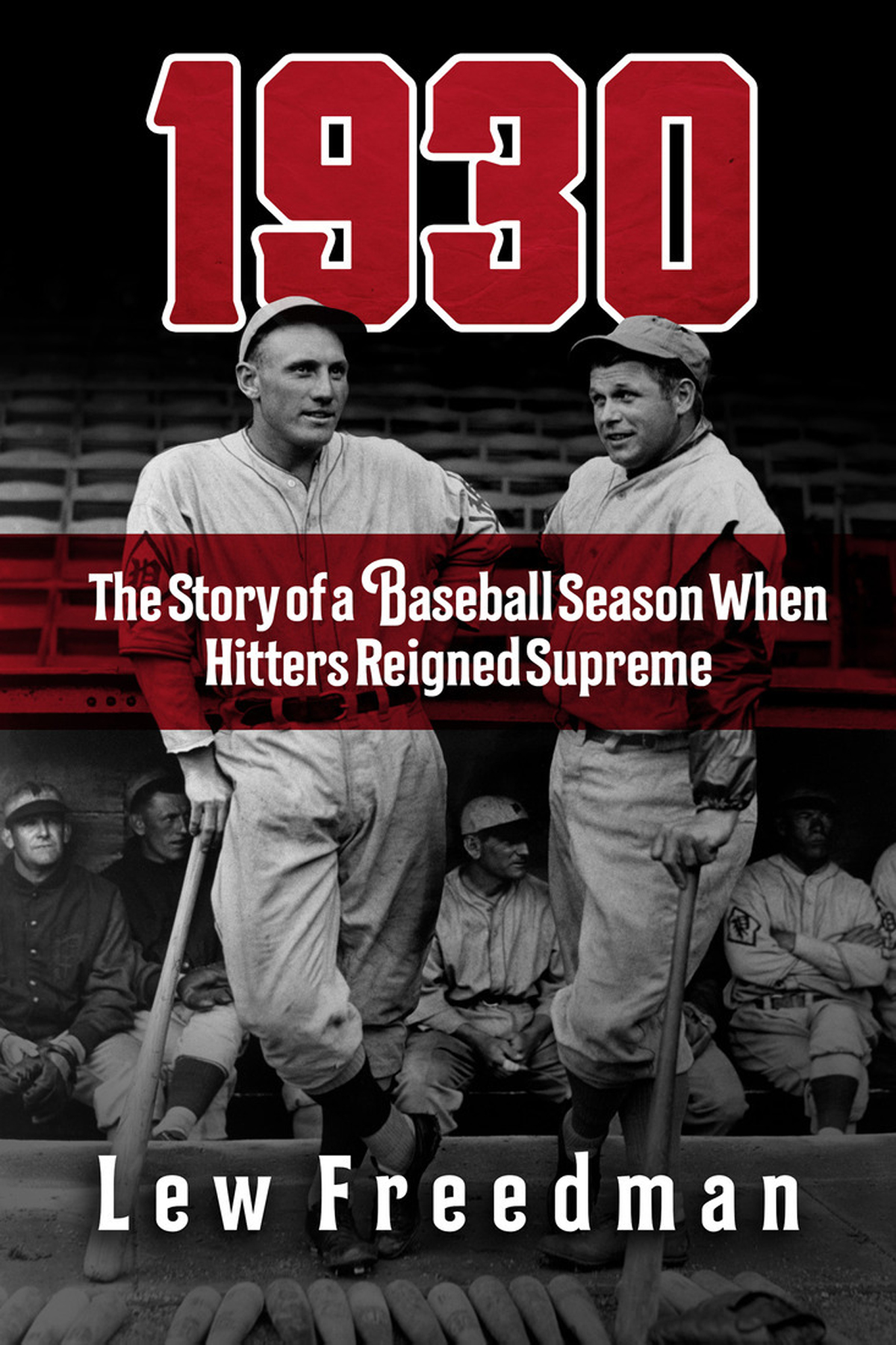

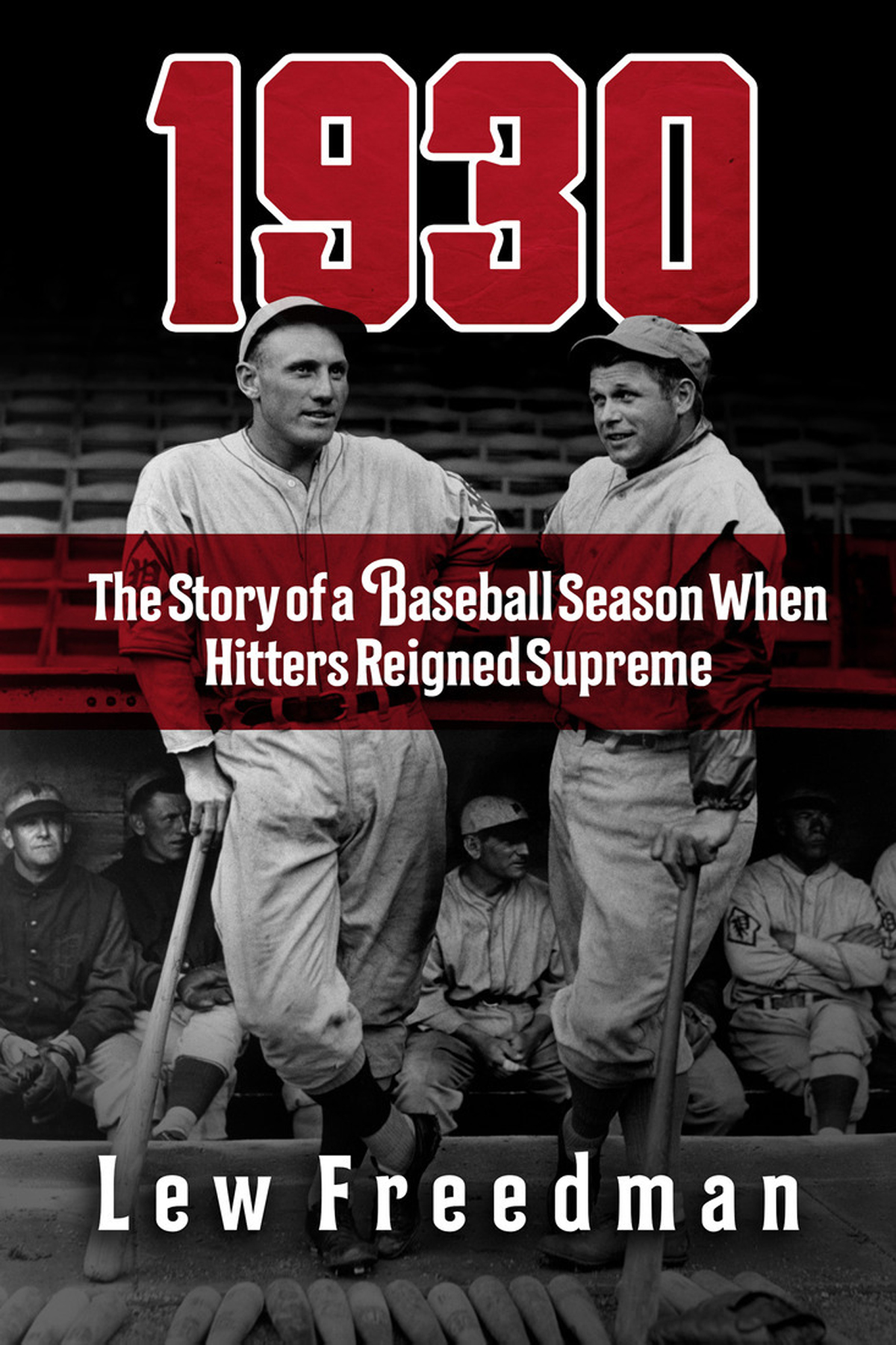

Jacket design by Kai Texel

Front jacket photo credit: Getty Images

Back jacket photo courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection

Print ISBN: 978-1-68358-420-9

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-68358-421-6

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

PREFACE

T HE 1930 MAJOR League Baseball season was unique. It was a hitters paradise, a fantasy world for the batter. It was a fluke, an aberration in the history of the game. The National League was founded in 1876, a quarter of a century ahead of the American League, and the sport was still going strong into the twenty-first century... but 1930 was an outlier. Never before or since have batters had their way with pitchers so readily, so easily, as they did during the summer of 1930.

The sixteen big-league teams put up pinball numbers in the scoring column and, at the same time, pitchers were in a nearly universal funk. It was as if almost every single major-league pitcher forgot how to throw; as if nearly everyone needed Tommy John surgery to fix what ailed them.

Of course, Tommy John the pitcher was not born until 1943, and the medical procedure that would repair so many injured elbows was not invented until decades later. Surely, most of the pitchers who suffered bombardment and humiliation in 1930 would have gladly sought out a seemingly magic antidote to the agonies of the moment.

More than ninety years have passed since the baseball campaign of 1930, so eyewitnesses are exceptionally scarce; all of the active participants deceased. Only baseball historians and avid fans recall the craziness of this solitary year. For fans of a particular team, the 1930 season does not stand out on a list, in terms of results. Perhaps only those with allegiance to the Philadelphia Athletics or St. Louis Cardinals would take notice.

For the other fourteen teamsespecially those that moved on to other locations over timethe season of 1930 would appear on no lists of accomplishments for fans to savor when discussing the good ol days. But what a season it would have been to watch unfold, more so for breathtaking individual achievements that stood out like flashing neon lights.

Above all, this was the year of Hack Wilson, who ruled the NL and all of baseballwith two remarkable batting statistics. Lewis Robert Hack Wilson owned 1930, his club of a bat producing long-revered and admired statistics, at least one of which has never been duplicated. He was the Babe Ruth of the National League for one, brief, shining moment. Even as the actual Babe Ruth was still slugging away in the American League.

The 1930 season is to be remembered for Bill Terry as well, with the New York Giants first basemans .400 average a forerunner of awareness that such batsmen were about to become endangered species.

Chuck Klein of the Philadelphia Phillies, also on his way to the Hall of Fame, might well have won a Triple Crown in any other season (40 HRs, 170 RBIs, .386 BA). Instead, his power totals in home runs, runs batted in, and average led the National League in nothing.

Wally Bergers 38 home runs for the Boston Braves set a record for rookies that stood until 1987, when Mark McGwire blasted 49 homers for the Oakland As.

It was the year of George Showboat Fisher, too; budding superstar, it might be thought. But rather it turned into the year of Showboat Fisher; a supernova, flashing briefly across the night sky and then becoming lost in some distant galaxy.

Some of the best pitchers in historyHall of Famers, in fact were bruised and battered by the time the 1930 season ended. These men recorded terrific accomplishments over long careers, but in 1930 they seemed more like journeymen.

Two starting pitchers, rarities among their brethren, were able to retire hitters in the same fashion they always had and would. Predominant among the breed was Lefty Grove and Dazzy Vance. While nearly all others faltered, they continued to excel somehow when it came to denying runs. They were in leagues of their own.

Grove and Vance were just about the only ones who didnt have to take cover from the barrage of line drives clouted up the middle and over the heads of the others who were bold enough to take a turn on the mound. Duck! had to be the best advice shouted by teammates that season.

For the first time in baseball history, a team scored more than 1,000 runs in a season (and this was during a 154-game season), when the New York Yankees compiled 1,062. Also, for the second time in history, too, since the Cardinals were right behind New York with 1,004 runs scored.

The National League as a whole batted .303, and that was with pitchers in the lineup full-time. The Giants team average was .319. The Phillies hit .315, and St. Louis .314. The two worst-hitting team totals were .281, the statistics of the Cincinnati Reds and Boston Braves.

Not only did all eight regular position players for the Cardinals bat at least .303, but four more backups, appearing in at least 45 games, also hit at least .321. Overall, sixty-two players hit .300 during the 1930 season, forty-two of them batting at least .320, and seventeen hitting at least .350. And twenty players stroked at least 200 hits. For many good players, collecting 200 safeties in a season was a once-in-a-career accomplishment.

As the inverse of the eye-opening hitting statistics, some of the worst earned-run averages imaginable were recorded by pitchers who, in other eras, might have swiftly been demoted to the minors. The Washington Senators 3.96 was the only team earned-run average under 4.00. The Phillies was a hold-your-nose 6.71.

The 1930 season was a tipping point for baseball and the country as a whole. For the decade of the 1920s, baseball had embraced the refreshing breeze of the Lively Ball Era in conjunction with the Roaring Twenties. Now, at the start of a new decade, the sport was pondering if it had fallen for too much of a good thing just as the Great Depression was beginning to deliver a sobering blow to the good times of the last decade.

Americans were about to be bludgeoned on the baseball field and at the bank.

PRELUDE

B ABE RUTH DID not invent the home run, but he might as well have.

Until George Herman Babe Ruth Jr. revolutionized baseball with his powerful uppercut swing, big stick, and larger-than-life personality, the sport was played in a different manner. The game was about scoring one run at a time, station-to-station, base-to-base, as opposed to clearing the bases with a single swipe.

Ruth, born February 6, 1895, in Baltimore, Maryland, was right on time, possessor of a blossoming man-child personality and a devil-may-care attitude. That, combined with his prowess on the baseball field transformed him into one of the grandest of mainstream celebrities at a time when the United States was ripe for indulgence.

Next page