First Mariner Books edition 2018

Copyright 2017 by Sridhar Pappu

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Pappu, Sridhar, author.

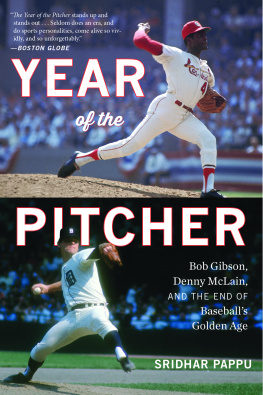

Title: The Year of the Pitcher : Bob Gibson, Denny McLain, and the End of Baseballs Golden Age / Sridhar Pappu.

Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, [2017] | Includesbibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017049609 (print) | LCCN 2017044909 (ebook) | ISBN 9781328768131 (ebook) | ISBN 9780547719276 (hardback) | ISBN 9781328557285 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Gibson, Bob, 1935 | McLain, Denny. | Pitchers (Baseball)United StatesBiography. | BaseballUnited StatesHistory--20th century. | World Series (Baseball) (1968) | BISAC: SPORTS & RECREATION / Baseball / History. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Sports. | HISTORY / United States / State & Local / Midwest (IA, IL, IN, KS, MI, MN, MO, ND, NE, OH, SD, WI).

Classification: LCC GV865.G5 (print) | LCC GV865.G5 P37 2017(ebook) | DDC 796.3570922 [B] dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017049609

Cover design by Martha Kennedy

Cover photographs Walter Iooss Jr./Getty Images (top), Focus on Sport/Getty Images (bottom)

v4.1218

For My Mother

Prologue: Hope

I N OCTOBER 1968 A year in which, as we all know, assassins made martyrs out of two good men, young soldiers with no other option waged a faraway war while their privileged peers fought to end that same conflict, and a newly militant citizenry laid waste to their own cities and homesDetroit Tigers pitcher Denny McLain opened the door of his bright new white Cadillac for Bob Gibson. Gibson was the ace of the St. Louis Cardinals staff. It was October and the World Series, an event that still mattered to a great many, had begun, and had things gone according to script, these two were to be its stars.

Bob Gibson and Denny McLain had already pitched against one another in St. Louis. Now the two were scheduled to face off against each other again in Game 4in what was billed as a World Series marked by pitching prowess the world would remember forever. Yet here they were together, having just finished taping an episode of The Bob Hope Show at the local NBC affiliate in Detroit. Paired at the end after absurd appearances by John Davidson and Gwen Verdon and Jeannie C. Riley, the two had been alongside Hope in a painfully unfunny, stilted scene in a medium struggling to stay relevant.

By then, Bob Hope, now 65, had been on television for more than 18 years. Yet it is fair to say that little remained of that Bob Hope, who had seemed like a tot to one New York Times critic when he was first unleashed from the restrictive playground that was radio and surged onto television with the force of an ex-boxer and a dancer, both of which he had been. The radiant Hope, the man whod held his own with Natalie Wood in dance numbers and brought the movement and speed of vaudeville back from extinction, simply stopped moving at the precise moment in American history when such immediacy and pace seemed the definitive tenor of the age.

As he welcomed McLain and Gibson, Hope looked, and acted, older than his years. Young people werent interested in him or his skits and jokes anymore. He was now a hardened iconoclast, a symbol of an establishment desperately trying to hold on to cultural power... and losing.

Standing to Hopes left was Gibson, a strikingly handsome black man, a perfect physical specimen save for a small gap between his two front teeth. Dressed immaculately in a Nehru jacket and white turtleneck, a gold medallion on his chest, Gibson looked like a man of his time. He was a man of great taste who dressed without equal, according to his friend and catcher Tim McCarver. No one, McCarver would later joke, could wear a pair of pants like Bob Gibson.

McLain should have taken note. Though eight years Gibsons junior, McLain looked worn out. His face was droopy and exhausted, his hair cemented into place. His baby-blue suit seemed to hang off him as his turtleneck bulged at the neck. All season hed promoted himself relentlessly, appearing on one television show after another, boasting endlessly about a salary increase that, in the era before free agency and arbitration, tight-fisted team management would never approve. He indulged his appetite for a flashy lifestyle and kept apart from his teammates. This was his moment on the big stage, but he was overshadowed by Gibsons cool.

The image of these two that day is unforgettable. Because whether they like it or not, McLain and Gibson are forever linked in our minds and in baseball history as the standard-bearers for 1968, the so-called Year of the Pitcher. That was the year when no less than five starters in the American League finished with an earned run average below 2.00. That year Juan Marichal used his arsenal of arm angles to win 26 games while logging a little over 325 innings, and Gaylord Perry of San Francisco and Gibsons teammate Ray Washburn pitched back-to-back no-hitters in consecutive games against one anothers teams. That was the year when Catfish Hunter threw a perfect game and Don Drysdale, in the waning stages of his career, emerged from the shadow of Sandy Koufax to throw 58 scoreless innings.

Even today the numbers seem unfathomable. Seven times that season a pitcherincluding Gibsonstruck out 15 hitters in a single game. There were 185 shutouts in the National League, and 154 in the American. Hitters were lost, offense nonexistent. It was a disparity so large that after the 1968 season Major League Baseball changed the rules in the batters favor in an attempt to restore balance. We would never see those kinds of numbers again.

But well always have that year. We will always have Gibson and McLain. Bob Gibson, St. Louis Cardinals: 1.12 ERA. Denny McLain, Detroit Tigers: 31 wins. In a game where the past is forever bumping up against the present, any conversation about pitching cannot help but return to these two names and the numbers they posted, which were nothing short of remarkable.

Its fair to say that had Gibson not been black, we would regard him differently. Hed be Joe DiMaggio, whose selfish silence played to a great many as the reserve of a dignified, stoic man. Or hed be Ted Williams, who redeemed himself over the years after a career in which he battled the Boston press and even the fans. We even gave Gibsons contemporary, the reclusive Sandy Koufax, his space. But Gibsons desire to keep to himself, to not play to the press, came off as the mark of the angry Negro, the face of the black power movement that had surged in popularity in the late sixtieseven though Gibson himself never believed in any of its precepts.

Then there was Denny. In all the ways Gibson remained aloof, Denny did not. We knew precisely who McLain was and whom he aspired to be. He was a man brazenly out for himself, who spoke openly about his financial interests at a time when ballplayers were still expected to keep quiet about money, to do as they were told, to treat the press politely and behave. His criminal entanglements were still unknown in 1968, but we knew that he lived life on the edge and that, even as he paraded his recklessness in public, he never doubted his invincibility. Like footballs Joe Namath, McLain saw his baseball career as just one part of a larger public persona, not the singular thing that defined him. It was Denny, with his playboy antics and lavish tastes, who presaged what lay ahead for baseball and American sport.