Table of Contents

Other Books by Robert Sobel

Dangerous Dreamers: The Financial Innovators

from Charles Merrill to Michael Milken

The Life and Times of Dillon Read

The New Game on Wall Street

RCA

ITT: The Management of Opportunity

N.Y.S.E.: A History of the New York Stock Exchange

Herbert Hoover at the Onset of the Great Depression

The Great Bull Market: Wall Street in the 1920s

For

Elizabeth Rose Sobel and Lauren Michelle Sobel

Had he been simply mediocre and commonplace, one would have gained no clearer impression of him at all. But just as a man may be so picturesquely ugly as to attract attention, so Coolidges personality was apparently so negative that it at once challenged human interest. In appearance he was splendidly null, apparently deficient in red corpuscles, with a peaked, wire-drawn expression. You felt he was always about to turn up his coat collar against a challenging east wind. As he walked there was no motion of the body above the waist. The arms hung immobile, with the torso as inflexible as the effigy of a lay figure.

In his enigmatic character he has been compared to the Sphinx. From the enigma standpoint the comparison is inexact; but like the Sphinx, he seemed to look out with unseeing eyes upon a world which held no glow, no surprises. Desert sand blown by the windendless, tantalizing dust.

Alfred Pierce Dennis, 1931

Meet Calvin Coolidge

It was my desire to maintain about the White House as far as possible an attitude of simplicity and not engage in anything that had an air of pretentious display. This was my conception of the great office. It carries sufficient power within itself, so that it does not require any of the outward trappings of pomp and splendor for the purpose of creating an impression. Of course there should be proper formality, and personal relations should be conducted at all times with the best traditions of polite society. But there is no need for theatrics.

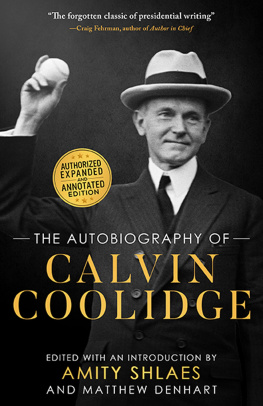

The Autobiography of Calvin Coolidge

AMERICAN INTELLECTUALS DO NOT so much harbor a negative opinion of Calvin Coolidge as they trivialize him. He often is dismissed as a political naif, simpleton, and lazy misfit, a relic from the nineteenth century, whose administration set the stage for the Great Depression. Most of the time, however, he simply isnt taken very seriously. Pulitzer Prizewinning historian Irwin Unger recently wrote, Coolidge slept away most of his five years in office. During his term, the watchword of government was do nothing. This is the image of Coolidge passed on to students and others. They have come to perceive Coolidge as an accidental president who lacked an agenda, did not call for sacrifices and crusades, and did none of those things that mark presidents usually considered great.

Do historians who hold this view have a point? They might observe there was no shortage of issues Coolidge might have addressed from 1923 to 1929, had he wanted to assert presidential leadership. The coal industry was a disaster area. In foreign policy there were Americas relations to the League of Nations and war debts. A response might have been mounted to the Japanese arms buildup. Harding had programs or recommendations to deal with most of these matters, and even before the Great Depression, his successor, Herbert Hoover, was a whirlwind of activity.

A major national debate centered around Prohibition. Coolidge disliked Prohibition, since he felt it could never work, but also because he generally opposed federal interferences with the ways people conducted themselves. He abhorred the Ku Klux Klan, and often spoke out for civil rights and against racism, but couldnt bring himself to condemn the Klans philosophy and actions directly or take any actions to create more harmonious race relations. The same was true for a bill that included a ban on immigration from Japan. He opposed this part of the measure, but signed it anyway.

For the most part, however, historians are silent on these matters. Indeed, a reading of many texts discloses most are scanted or not even discussed. Rather, there seems to be three reasons for his poor reputation, one being the perception that he took no steps to prevent the Great Depression, which is to say, he lacked the ability to foresee the futurea failure he shared with all presidents, and indeed, all humans. This one doesnt merit serious consideration, and in any case, Coolidges words and actions regarding the economy will be discussed in detail later in this book, and the reader can decide for himself or herself on the matter.

Another is the view of him as being indolent, and the business of sleeping away his time and doing nothing. Writing in 1926, Walter Lippmann touched upon this in an ironic but perceptive fashion.

Mr. Coolidges genius for inactivity is developed to a very high point. It is far from being an indolent activity. It is a grim, determined, alert inactivity which keeps Mr. Coolidge occupied constantly. Nobody has ever worked harder at inactivity, with such force of character, with such unremitting attention to detail, with such conscientious devotion to the task. Inactivity is a political philosophy and a party program with Mr. Coolidge, and nobody should mistake his unflinching adherence to it for a soft and easy desire to let things slide. Mr. Coolidges inactivity is not merely the absence of activity. It is, on the contrary, a steady application to the task of neutralizing and thwarting political activity wherever there are signs of life.

This is quite different from sleeping away five years in office.

C. Bascom Slemp, formerly Coolidges private secretary, gathered together the presidents thoughts on various subjects in 1926, in a work entitled

The Mind of the President. In words that Coolidge must have approved (though he denied having anything to do with the book), Slemp wrote:

He had reversed a recent tradition of the presidential office. For a quarter of a century our presidents have professed democracy but have practiced benevolent autocracy. They believed that they could advance the welfare of the nation better than the people could advance it. They announced what they declared to be progressive policies and tried to convert the people to these policies. They have tried to improve government from the top.

While this statement appears to place Warren Harding in the progressive tradition, the concept certainly can be easily defended. Slemp went on to say that Coolidge believed progress comes from the people, and that a national leader should not try to go ahead of this majestic army of human thought and aspiration, blazing new and strange paths. Lippmann went still further. Mr. Coolidge, though a Republican, is no Hamiltonian Federalist, and so he extended the time line to the first secretary of the treasury at least through Woodrow Wilson, during which the tendency of Hamiltonians and Republicans was toward centralization. This matter will be discussed on several levels in the pages that follow.

Finally, Coolidge is portrayed as one whose major concern while in office was to assist business, especially big business. It is upon this issue more than any other, and Coolidges supposed rhetoric rather than his actions, that they base their conclusions. One of the objects of this book is to demonstrate that his words and actions were more complicated on the matter than is commonly thought, and also to examine and defuse other myths that have gathered around him.