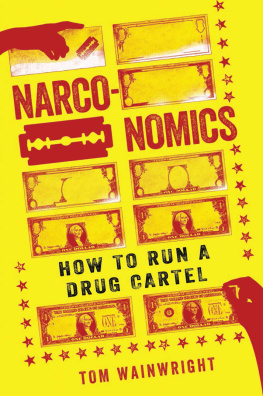

Copyright 2016 by Tom Wainwright.

Published in the United States by PublicAffairs,

a Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

PublicAffairs books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Book design by Timm Bryson

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wainwright, Tom, 1982 author.

Title: Narconomics: how to run a drug cartel / Tom Wainwright.

Description: First edition. | New York: PublicAffairs, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015032727| ISBN 9781610395847 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Drug trafficEconomic aspects. | Drug controlEconomic aspects. | Drug dealers.

Classification: LCC HV5801 .W325 2016 | DDC 363.45dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015032727

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Crooks already know these tricks. Honest men must learn them in self-defense.

HOW TO LIE WITH STATISTICS, DARRELL HUFF

Table of Contents

Guide

Contents

Photographs appear following

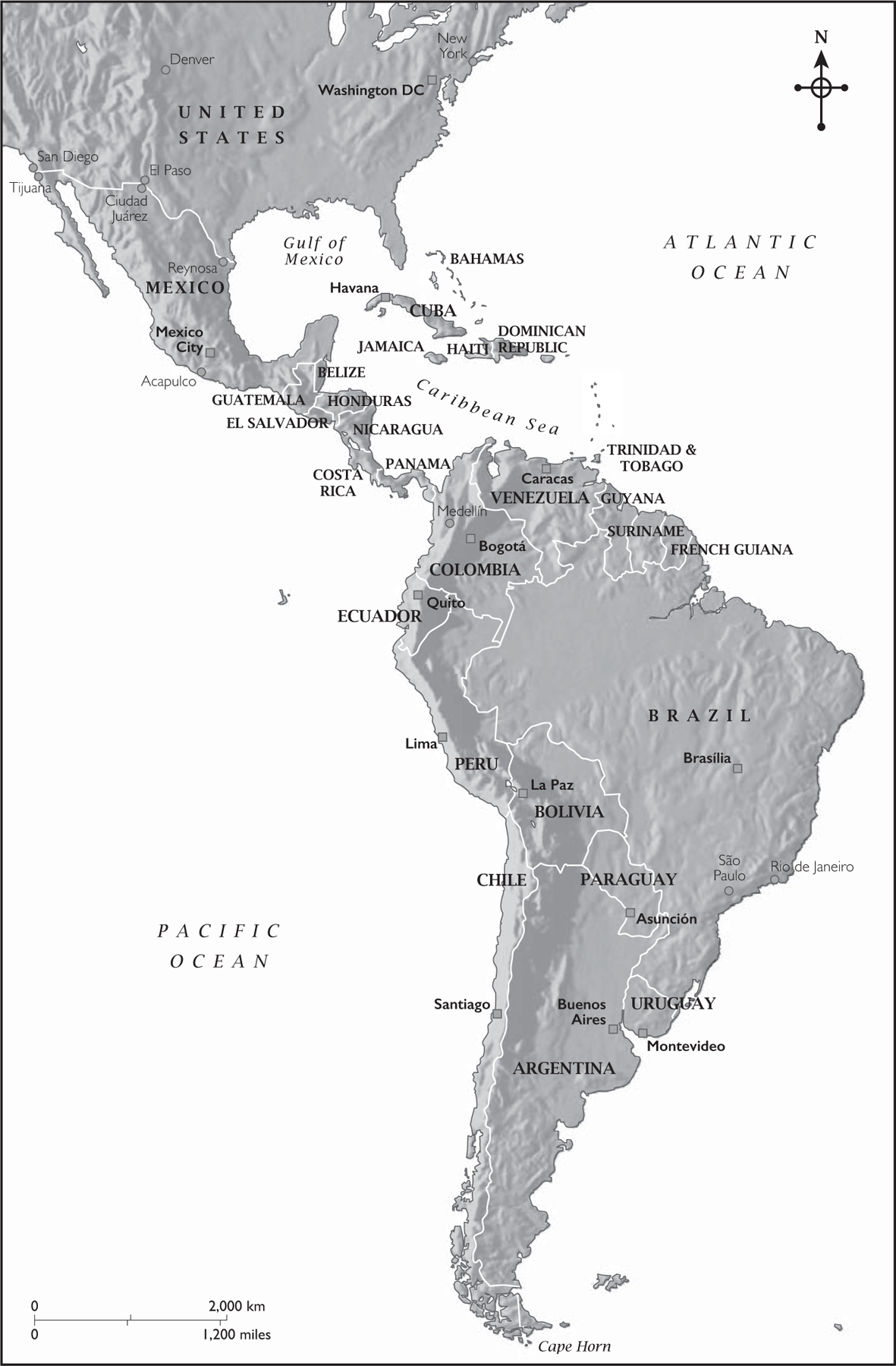

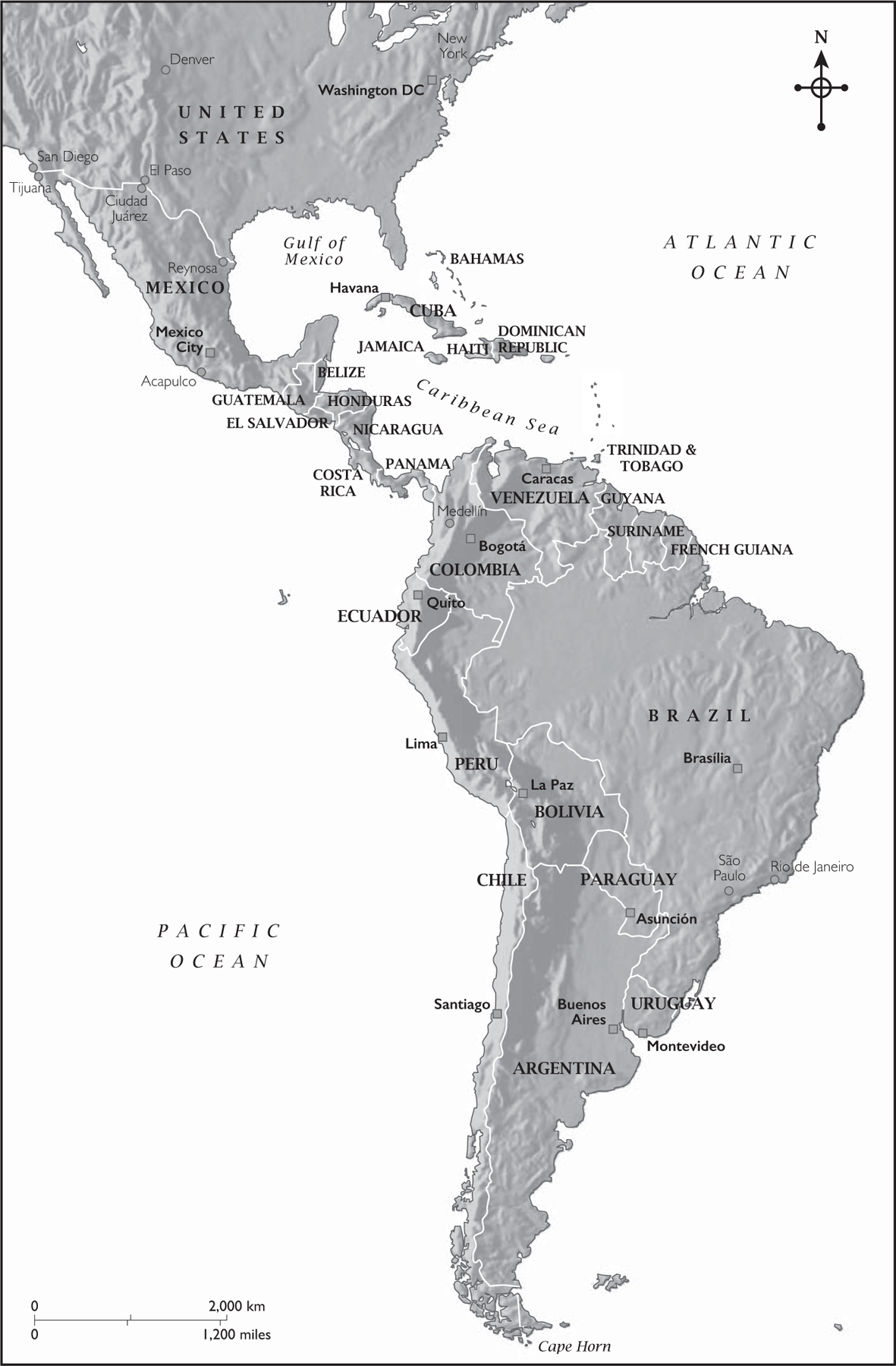

Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to Ciudad Jurez, where the local time is 8:00 a.m. On a chilly November morning on a runway in the Mexican desert, one passenger onboard Interjet Flight 2283 is fiddling nervously with a small package hidden in his sock, wondering if he has made a terrible mistake. Jurez, a brash border city of scorching days and freezing nights, is the main cocaine gateway to the United States. Shoved up against the metal fences of the Texas border, exactly halfway between the Pacific and the Gulf coasts, it has long been a smugglers hangout: a place where illicit fortunes are made and blown on fast cars, gaudy mansions, and usually before very long, spectacular mausoleums. But the nervous passenger, now blinking in the morning sun as he walks to the terminal, noting the camouflaged, balaclava-wearing marines guarding the exit, is not a drug mule. The passenger is me.

Inside the terminal I find the nearest bathroom, lock myself in a cubicle, and pull out the package, a small, black, electronic gadget, about the size of a cigarette lighter, with a single button and an LED light. A few days earlier, in Mexico City, it had been presented to me by a local security consultant who feared that the nave young britnico before him might get into hot water on his trip to Jurez. Now, at the time of my first visit, the place has recently earned the title of worlds most murderous city, thanks to the deadly game of hide-and-seek being played by rival cartel hit men across its colonial downtown and cinderblock slums. Roadside executions, mass graves, and inventive new forms of dismemberment fill the local newspapers and television reports. Inquisitive journalists, in particular, have a habit of disappearing into car trunks, mummified in masking tape. Jurez is not a place to take any chances. So what I should do, the consultant had explained, handing me the device, is press the button when I arrive, wait for the LED to come on, and keep the gadget hidden in my sock. As long as the light is blinking, he will be able to track my whereaboutsor at least those of my right legshould I fail to check in.

In the cubicle, I quietly take out the tracking device, turn it over in my hands, and press the button. I wait. The light remains dead. Puzzled, I press it again. Nothing. Jabbing, hammering, holding the button down: whatever I do to try to coax the device to life over the next few minutes, the light refuses to blink. Eventually I stick the useless thing back in my sock, gather up my things, and make my way warily out onto the streets of Ciudad Jurez. The gadget is dead, and I am on my own.

This is the story of what happened when a not very brave business journalist was sent to cover the most exotic and brutal industry on earth. I arrived in Mexico in 2010, just as the country was starting to ramp up its war on the narco-cowboys, who, with their gold-plated Kalashnikovs, had reduced some parts of the country to a state of near anarchy. The number of people murdered in Mexico in 2010 would reach more than twenty thousand, or about five times the figure recorded across all of Western Europe. The following year was to be more violent still. News bulletins featured little else: every week brought new stories of corrupted cops, assassinated officials, and massacre after bloody massacre of narcotraficantes, by the army or each other. This was the war on drugs, and it was clear that drugs were winning.

I had sometimes written about drugs from the point of view of the consumer, in Europe and the United States. Now, in Latin America, I was confronted with the narcotics industrys awesome supply side. And the more I wrote about el narcotrfico, the more I came to realize what it most closely resembled: a global, highly organized business. Its products are designed, manufactured, transported, marketed, and sold to a quarter of a billion consumers around the world. Its annual revenues are about $300 billion; if it were a country, it would rank among the worlds forty largest economies. The people who run the industry may have a sinister glamour about them, with their monstrous nicknames (one in Mexico was known as El Comenios, or The Childeater). But whenever I met them in person, their boasts and complaints tended to remind me of nothing so much as those of corporate managers. The head of a bloodthirsty gang in El Salvador, who boasted to me in his baking prison cell about the amount of territory controlled by his compaeros, spouted platitudes about a new gang-truce that could have come directly from the mouth of a CEO announcing a merger. A burly Bolivian farmer of coca, the raw ingredient of cocaine, enthused about his healthy young narco-crops with the pride and expertise of a commercial horticulturalist. Time and again, the most ruthless outlaws described to me the same mundane problems that blight the lives of other entrepreneurs: managing personnel, navigating government regulations, finding reliable suppliers, and dealing with competitors.

Their clients have the same demands as other consumers, too. Like customers of any other industry, they seek out reviews of new products, increasingly prefer to shop online, and even demand a certain level of corporate social responsibility from their suppliers. When I found my way into the hidden Dark Web of the Internet, where drugs and weapons are anonymously bought with Bitcoins, I dealt with a trader of crystal-meth pipes who was as attentive as any Amazon representative. (Actually, I take it back. He was far more helpful.) The more I looked at the worldwide drug industry, the more I wondered what would happen if I covered it as if it were a business like any other. The result is this book.

Next page