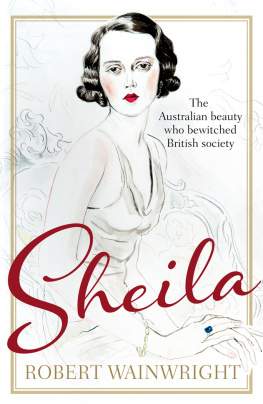

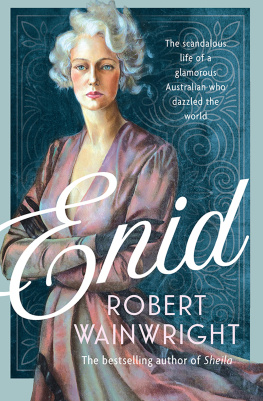

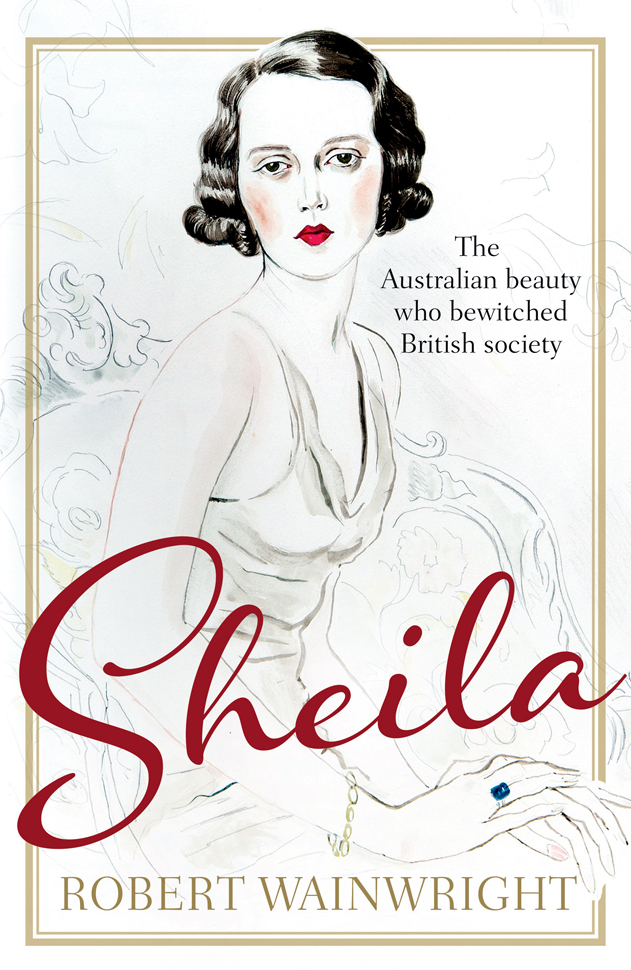

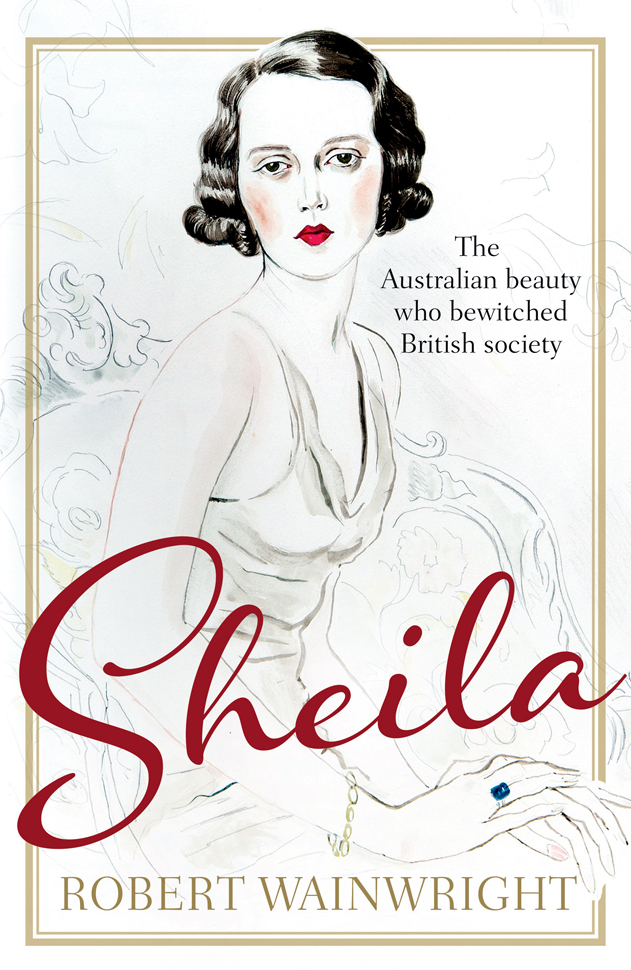

ROBERT WAINWRIGHT

First published in 2014

Copyright Robert Wainwright 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: info@allenandunwin.com

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available

from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74331 131 8

eISBN 978 1 74343 156 6

Internal design by Lisa White

Set in 12.5/18 pt Minion by Post Pre-press Group, Australia

Image credits:

(Margaret) Sheila MacKellar (ne Chisholm), Lady Milbanke (18951969) by Cecil Beaton National Portrait Gallery, London

Lady Milbanke as Penthesilea, the Queen of the Amazons Madame Yevonde Archive Lady Sheila Milbanke by Simon Elwes RA (19021975) Peter Elwes

All other images The Earl of Rosslyn

To my own Sheila, Paola,

and in loving memory of my late father, Arthur

CONTENTS

The lady graced, rather than sat on, the hotel couch; at ease, as one might have expected, in the luxury of her temporary surroundings. Her face, famed in her youth for its ethereal beauty, was still bright and eager, her make-up spare. Wide clear eyes creased faintly when she smiled, framed by thick, carefully styled silver hair that sat shoulder-lengthlonger than in her heyday, when she had helped make short, sharp hair fashionable. Pixyish, an admirer and frustrated suitor had once described her. That compliment still held true four decades after it had been given.

But she had some other, special quality. Her interrogator, the womens magazine journalist perched on a chair opposite, scrambled mentally for the phrase that might definitively encapsulate the woman before her. It was on the tip of her tongue, and yet somehow elusive. Prim or matronly did the lady a disservice, despite the cascading strings of pearls around her throat and the modest length of her skirt in this summer of 1967. Even graceful was too simplistic an assessment of a woman with an air that evoked much, much more. Then it came to herregal. She had a bearing that could only have come from a life of stature.

The ladys name was Princess Dimitri Romanoff, but she was Russian only by name. As Sheila Chisholm she had been born and raised on a sheep and horse station on the Goulburn Plains in southern New South Wales, where she defied her parents and smoked at the age of twelve and rebelled against well-meaning but demanding governesses: Mother told me she would never keep on a governess who was unkind to me so, whenever they actually tried to teach me something, I said they were being unkind. Governesses came and went like butterflies. I was a monster, she confided to the journalist, with a half smile and only a hint of contrition.

But this same wilful child would become as intimate with royalty as any Australian woman of her time. Born into a family that had helped settle and explore Australia and then craft the European settlement from the days of the early fleets, Sheila, as she would always call herself, left Australia as a teenager in 1914 just as political rumblings stirred fear of a war in Europe. She would return home just three times in the next fifty yearsher first visit as the wife of a Scottish lord, her second as the wife of an English baronet, and now as the wife of a Russian prince. Through it all, she remained quintessentially an Australian country girl.

I married all my husbands for love, shed told a throng of media waiting at Sydney Airport when she had arrived a few days earlier. I certainly didnt care about titles, and none of them had any money.

In the forty-eight hours since arriving in Sydney the prince and princess had lain low, taking their time acclimatising to the twin demands of time and seasonal change. They had come from the twilight and damp cold of an English winter to the glazing, steamy heat of an Australian summer; the temperature had bubbled at over 102 degrees Fahrenheit (39 degrees Celsius) when theyd arrived at Sydney Airport and sat in a room with a broken air conditioner while three television stations took their turns interviewing the couple. One reporter, sensing their distress, had offered Prince Dimitri a glass of water. His replyNo thank you; I never drink waterdelighted them; they interpreted it as the motto of a vodka man without knowing he had once made his living selling whiskey.

Sheila knew the impact of change more than most. Her life had been shattered twice by world warsher first marriage devastated, at least partly, by the impacts of the Great War on her psychologically-fragile husband and the life of one of her sons taken in battle during World War II.

Traumatic upheaval had haunted her generation, as the man who now sat beside her could testify. As a young man Prince Dimitri had escaped the violence of the Bolshevik Revolution, which had claimed the life of his uncle, the last Tsar of Russia, Nicholas II. His family had been under house arrest for eight months before they were rescued and taken to London; he was one of only thirty-five of the famed Romanoffs who survived. In reply to a question from the magazine writer, he recalled: We slept in our clothes, always hoping for escape. We were starved. He had survived, rescued by the English King, George V, but, notwithstanding his grand title, he had spent most of his adult life working, including some years in the United States as a factory worker making refrigerator parts.

His wifes life had been the opposite: born in the obscurity of the Australian bush but, by a combination of fate and opportunity, finding her way to the centre of the world, in London. In her heyday the public had been fascinated by Sheilas life, which had been reported on regularly over the years, not only by Fleet Street but by newspapers across the United States and the sub-continent. Back home, even the smallest regional papers had carried regular reports gleaned from the wire services, for readers eager to explore her success and wonder how a young woman from the plains outside Canberra had managed to spend half a century inside the palaces, mansions and clubs of the rich and powerful.

Sheilas story was deliciously evocative, as the reporter would observe in her feature article for The Australian Womens Weekly: When you talk to [her] the air seems to fill with the ghosts of a long-ago glittering world, with the sound of far-off trumpets, the swirl of beautiful Court dresses, the flash of light of ceremonial swords.

The newly federated Australian nation was still finding its feet when Sheila Chisholm left its shores with her mother Margaretwife of the pastoralist, grazier and prominent racehorse breeder, Harry Chisholmand headed for the social glamour of Europe: Canberra didnt exist when I left, she reminisced; the national capital was still a political wilderness in the middle of nowhere, with barely a shovel hole. Its development would be further delayed when the Great War was declared a few months later, which meant she had not seen it until now.

Next page