Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To my daughters, Rose and Alice, with love

I would like to thank the following for their help in the preparation of this book: the Hallward Library, University of Nottingham; Cambridge University Library; Charlie Viney at the Viney Agency; Charlie Spicer and April Osborn at St. Martins Press; Kim Lewis; the Victoria and Albert Museum; Getty Images; the Mary Evans Picture Library; Curtis Brown for permission to quote from The Edwardians by Vita Sackville-West; the Gardens of Easton Lodge Preservation Trust; and finally, my husband and daughters for their support, tact, and forbearance while I completed this book. There are no words apart from thank you, with all my heart.

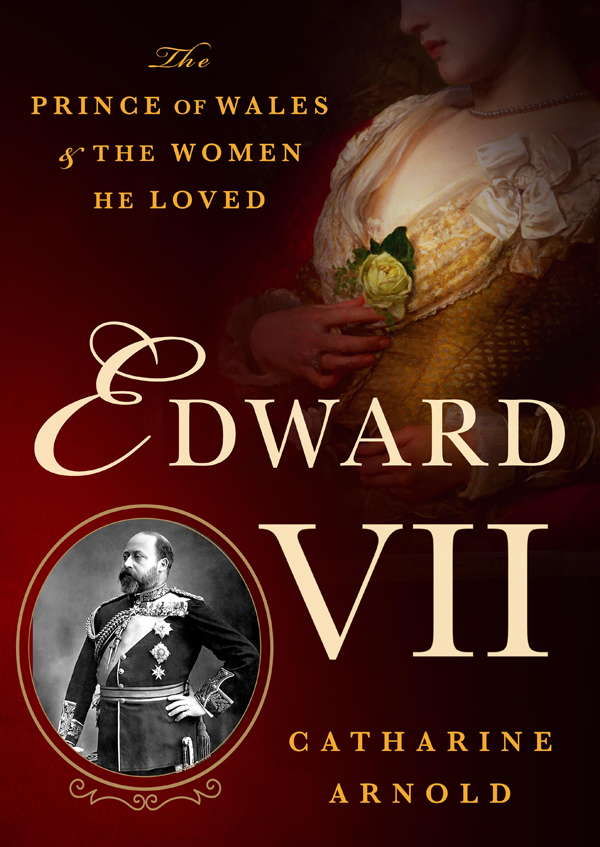

As guests thronged into Westminster Abbey to take their appointed places for the coronation of King Edward VII on August 9, 1902, they were greeted by a bizarre spectacle. This was a pew reserved for the Kings special ladies, whose rank did not automatically entitle them to a place in the Abbey, and christened the Kings loose box by one of the deputy marshals, James Lindsay, Earl of Crawford.

The term loose box, derived from horse racing, was appropriate enough, although the pew was more like a winners enclosure than a loose box. Bertie, as the king was fondly known, doubtless regarded the coronation as another opportunity to display his thoroughbred fillies and thank them for their years of loyal service. But some guests were left shocked and appalled by the sheer effrontery of inviting the royal concubines to the coronation.

It was the one discordant note in the abbey, wrote one of Queen Alexandras ladies-in-waiting. It did rather put my teeth on edge; there was La Favorita [Alice Keppel] of course in the best place, Mrs Ronnie Greville, Lady Sarah Wilson [ne Spencer-Churchill, the first woman war correspondent who had covered the Boer War for the Daily Mail ], Lady Feodorovna Feo Sturt [daughter of the Earl of Hardwicke], Mrs Arthur Paget [Minnie Stevens, the Anglo-American society hostess], & that ilk. This ilk also included Lillie Langtry, Sarah Bernhardt, Jennie Churchill with her sister, Leonie, Sophia, Countess of Torby, Lady Albemarle (Alice Keppels mother-in-law), and Princess Daisy of Pless, daughter of Patsy Cornwallis and quite possibly the daughter of Bertie, too. Next to Alice sat Baroness Olga de Meyer, whom Bertie believed was his natural daughter by the Duchess di Caracciolo, although Olgas paternity was the subject of much speculation.

The most prominent men and women in the land witnessed the eighty-year-old Archbishop of Canterbury unsteadily lower the imperial crown onto the head of Edward VII, in the presence of the kings past and present lovers. If you can tell a man by the company he keeps, then these ladies tell us everything we want to know about the character of Edward VII, henceforth referred to as Bertie.

Charming and dissolute, Bertie admired beautiful, spirited women who were good sports, in and out of bed. Bertie loved smart women who sparkled in his company, but he had a horror of highbrows, particularly writers! according to his lover Daisy, Countess of Warwick.

The women Bertie loved had one thing in common: they were nothing like his mother, Queen Victoria. Warm, generous, lively, Berties women were the polar opposite of the reclusive Widow of Windsor. Queen Victorias pathological mourning for her husband, Prince Albert, who died in 1861, might have been endurable if young Bertie had ever felt that his mother loved him. But Victoria seems to have hated her oldest son from birth, and later, after learning of his first affair, wrote that I never can or shall look at him again without a shudder. No wonder the welcoming arms of any woman, from countess to courtesan, were attractive, after the Queens froideur.

Bertie also possessed a ruthless streak. He was a dangerous man to cross. Bertie never forgives, as one companion observed after a particularly difficult episode. For all those women who sat in the kings loose box, and the patient Princess Alexandra, or Alix, who stood by him for all those years and eventually became his queen, there were also victims. These included a lonely woman who died in exile, another confined to a madhouse, and a young widow who was willfully cast aside after falling pregnant. Bertie had no scruples in destroying those who betrayed or offended him.

One wonders what the atmosphere must have been like in the loose box. Did it bristle with a spirit of competition, or, by this stage in Berties life, was there a spirit of female solidarity in the harem? Every one of those women knew that Alexandra, the patient Danish princess who had been married to Bertie since 1863, was the queen in every sense. Not a woman there would have deluded herself that she could have displaced Alix; these were the days when royal mistresses were tolerated, even encouraged; it was practically a court rank in itself. No heir to the throne would have stepped aside to divorce and remarry; it would be more than thirty years before Edward VIII abdicated in order to marry the woman he loved. Bertie was king by divine right and his marriage was sacrosanct, no matter how many dalliances and flirtations he indulged in. It was Alix, when Bertie died, who declared, But he loved me the best! For the ladies of the loose box, becoming Berties mistress allowed them to revel in a little reflected glory before, inevitably, he lost interest and another woman took their place.

Alix was a woman for whom the description long-suffering wife might have been invented. Alix endured Berties endless indiscretions from the earliest days of their marriage, when he went off to Paris while she was experiencing a difficult first pregnancy. As Berties indiscretions became common knowledge, Alix gained in popularity and adoration. The Princess of Wales floated through the ballroom like a vision from fairyland, The fact that Alix was called the Princess of Hearts makes it easy to draw comparisons with the late Princess Diana, but there was to be no divorce for Alix. She stayed with Bertie and took some consolation in a platonic romance with an adoring courtier, Oliver Montagu.

Meanwhile, Bertie, larger than life with king-sized appetites, conducted his liaisons against the glittering backdrop of London society, the Continent, and the stately homes of England, where a strict code of honor insulated the nighttime corridor creepers from scandal. In Paris, Bertie was a regular at the Moulin Rouge music hall, where his nickname was Kingy! and the dancer La Goulue yelled to him from the stage, Oi, Wales! Are you goin to pay for my champagne?

Much of Berties behavior seems born from boredom; denied the throne, as Queen Victoria resolutely refused to abdicate, Bertie was stuck with the path in life that fate had dictated for him. He was faced with two options: to bow to convention or to live life by his own rules. And those rules were not so very different from those of other upper-class men in the late nineteenth century. As Anita Leslie, author of Edwardians in Love, commented, it is hard to dislike Bertie. After all, he merely wanted to go to bed with a lot of women and took advantage of unparalleled opportunities. Would many men act differently if put in his place?