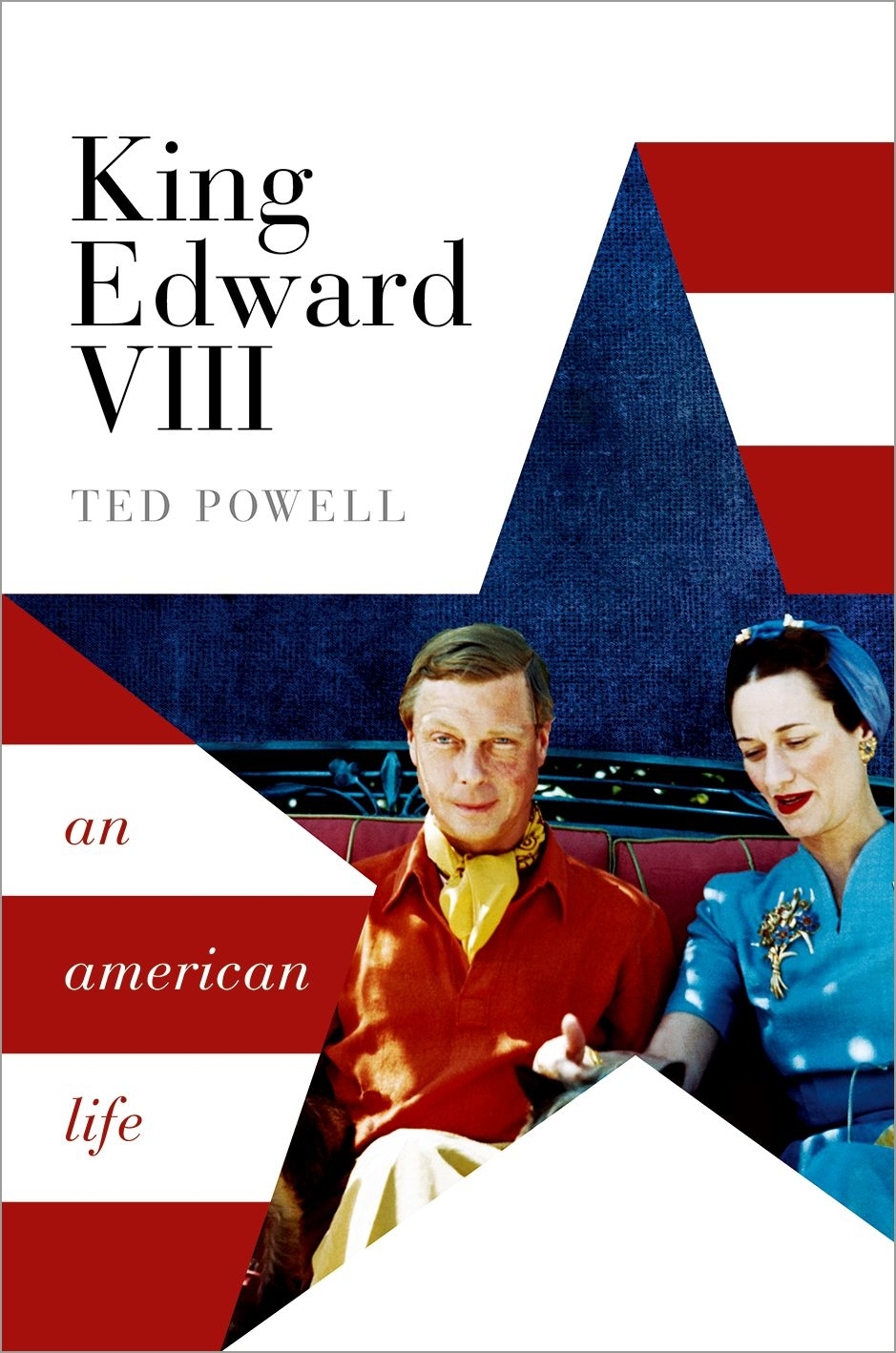

King Edward VIII

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox2 6dp, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Ted Powell 2018

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2018

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirerPublished in the United States of America by Oxford University Press198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018942362

ISBN 9780198795322

ebook ISBN 9780192514578

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith andfor information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materialscontained in any third party website referenced in this work.

For Alison, who married one Edward, and found herself living with two

Acknowledgements

I have incurred many debts of gratitude in the course of writing this book. In the early stages I was fortunate to receive helpful advice on planning, structure, and possible publishers from David Cannadine, Tom Penn, Andrew Rose, Ruth Scurr, Catherine Clarke, Caroline Burt, and Richard Partington. Throughout my research I was greatly helped by the expert assistance of archivists and staff at the National Army Museum, the Imperial War Museum, the Cumbria Record Office, the Churchill Archives Centre, the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, Alberta, the London Metropolitan Archives, and the Parliamentary Archives. A happy reunion with my old editor Robert Faber led to a renewed working relationship with Oxford University Press. In Alberta, my wife and I enjoyed the generous hospitality of Jennifer Bartlett as she showed us the wonderful restoration work that she and her husband Curtis are carrying out on the EP ranch; Andrew Wood supplied me with valuable information on Edwards interest in aviation; Charles Metcalfe provided fascinating information on his grandparents, Edward Fruity Metcalfe and Lady Alexandra Curzon; while Katherine Mann provided inspiration on marketing and promotion. Thanks also to my editors at OUP, Matthew Cotton and Kizzy Taylor-Richelieu for all their patience, diligence, and good humour.

The book has been substantially written over the last two years, while I was taking part in the Guardian/University of East Anglia Masterclass on the New Biography, led by Professor Jon Cook. Jon has read virtually the entire book in draft, providing guidance and constructive criticism at every stage of production. He has truly been the midwife in the delivery of the book. My fellow students on the course, Liza Coutts, Diana Devlin, Carrie Dunne, Monique Goodliffe, Lyn Innes, Jo Rogers, Barbara Selby, Ann Vinden, David Warren, and Hephzi Yohannan, have given me tremendous support and encouragement. This is only the first of many published works which will emerge from the class in due course.

My greatest debt is to my family. My father, the late Ray Powell, first awoke my love of history, and I like to think he would have enjoyed reading the book. My mother, Avril Powell, shared with me reminiscences about Edward from her childhood, and provided a very congenial working environment when I went to stay with her. My daughters, Helena and Juliet, have helped me more than they know. I have often benefited from Helenas encyclopedic knowledge of Queen Victorias family, while Juliet provided insights into Edwards fantasies of escape, and Walliss identity as a Southern belle. My wife Alison has lived with Edward day-to-day for more than five years. There have been three of us in the marriage (to coin a phrase), so it has been a bit crowded. She has tolerated my obsession patiently, as the house filled with Edward memorabilia, books, busts, china, photographs, and bric-a-brac. She has read all the chapters in draft, and offered penetrating comment. The book could not have been written without her, and I dedicate it to her.

Contents

On 4 April 1970 President Richard Nixon welcomed the Duke and Duchess of Windsor as guests of honour at a dinner in the White House. As the visitors limousine pulled up, Nixon, looking unexpectedly elegant in white tie and tails, walked down the steps of the entrance to offer assistance to his elderly guests. The Duchess took his arm but the Duke managed with his walking stick. Inside about a hundred guests were waiting, mostly celebrities, film stars, and sportsmen: Fred Astaire, the golfer Arnold Palmer, and the Apollo 8 astronaut Frank Borman.

Figure 0.1. President Nixon entertains the Windsors at the White House, April 1970

Nevertheless it was a convivial occasion. The photographs show the Windsors basking in the limelight of the Presidents attention while Nixon, whose parents had named him after the medieval English king Richard the Lionheart, savours the faded glamour of the ex-king. It was an intriguing encounter between the only British monarch voluntarily to abdicate the throne and the only US president to resign the office. Nixon had a vivid memory of listening to Edwards Abdication speech on the radio with his college friends, and later claimed that it had made more impression upon him than President Roosevelts fireside chats of the same era.

The American Presidents admiration for Edward was nothing new: the close relationship between Edward and the USA was of long standing. He had first visited Washington more than half a century earlier in November 1919, while on an official tour of North America as Prince of Wales. The occasion could not have been more different. Then he came as a guest of President Woodrow Wilson, and he arrived in the middle of a political crisis. The President was forced to welcome the Prince from his sickbed in the White House, his health broken by the protracted negotiations at the Versailles Conference after the Great War and his unsuccessful efforts to persuade the Senate to ratify the Peace Treaty. Edward spoke with Wilson for only a few minutes, and afterwards remarked that he had the most disappointed face that I had ever looked upon.

Edwards meeting with President Wilson came at the end of a year of frequent encounters with Americans. Im liking the Americans more than ever, he wrote excitedly after visiting American troops in January 1919. Im just longing to go to the States...but we just must be closely allied with the USA, closer than we are now, and it must be lasting and they are very keen about it. He was captivated by the energy, confidence, and raw power of the USA as it strode onto the world stage at the end of the Great War. Edwards tours of North America only served to strengthen that affinity. Fifteen years later, as war threatened Europe again, he told an American journalist: