A Random House eBook Original

Copyright 2012 by POLITICO LLC

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

eISBN: 978-0-679-64510-8

www.atrandom.com

v3.1_r1

Contents

The champagne had been flowing freely for hours in the presidential suite atop Chicagos Fairmont hotel when the networks got around to calling the race for Barack Obama at around 11:15 P.M. eastern standard time.

Obamas advisers, a block away in the seventh-floor boiler room at campaign headquarters, had known the thing was over since early evening. Their internal predictions for each state had been off by little more than 1 percent in any state; Ohio was tighter than they thought, but everything else was going according to plan.

Its not going to be all that fucking close, Chicago mayor Rahm Emanuel told a reporter earlier that night, way more than three hundred in the Electoral College.

At 11:38, the AP declared it done. Midnight tolled back east, then 12:15, 12:20. Many of the forty or so would-be revelers in the suite were starting to wonder, loudly, where was the concession call from Romney?

Giddy staffers began streaming in to congratulate Obama, joining family members and friends who had been there all night. They saw Valerie Jarrett talking, half jokingly, at the televised image of Romneys empty podium in Boston, a thousand miles to the east.

Come on, call! she said.

I was pissed, David Axelrod, Obamas closest message adviser for a decade, later told this books authors. It was just sort of childish to wait as long as he did.

Jim Messina, Obamas campaign manager, the man who had spent two years building the billion-dollar Obama operation from the ground up, called his Romney counterpart, Matt Rhoades. He didnt get him. Look, we got to do something; this race has been called, he said gently, leaving a message, according to a person nearby. Then he texted Rhoades to underscore the point.

If Romney didnt move quickly, there was talk of driving the president over to the McCormick Place convention center, where thousands of supporters and the national media were awaiting his victory speech, according to several top advisers.

In the suites bedroom, the thin man in a white shirt and blue silk tie perched on the bed making a few last-second changes to his second victory speech, with his alter-ego speechwriter, Jon Favreau, and Axelrod.

Obama, people around him would later recall, seemed unperturbed by the delay, in the mood to savor rather than to rush. It was over. His enemies had failedall the birthers, the Tea Party obstructionists who had written his obituary after the 2010 midterms, Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell, who vowed to make him a one-term president like Carter.

Those closest to Obama knew he always had an itch, a nagging sense that underneath the momentary adulation in 2008 people werent really voting for him, but against George W. Bush. It had just been swept away.

Theres no doubt that he found this one to be sweeter than the last one, said one of Obamas longest-serving advisers. It was weighing on him how much was at stake, how much of his entire legacy was on the line. His legacy had not been determined by the previous four years; that wouldnt matter to history. It was all about the outcome on Election Day.

After the tense, uncertain thirty-four days from Obamas big flop at the first debate in Denver to Election Day, Romneys dawdling was nothing short of excruciating. The jitters were getting to everybody, but especially to Jarrett, who navigated the incongruous role of Obama adviser and Obama family friend.

Why isnt he calling? she asked the group. We gotta go! We gotta go!

Obama tried to calm everybody down. Dont push This is hard. Hell call, dont worry, he said, according to one of his top aides. Look, he needs to do this in his own time.

Soon after, Messina peered down at his iPhone. It was a text from Rhoades: The governor will be calling in a few minutes.

Then, at 12:35 Boston timeeighty minutes after the race had first been calledMarvin Nicholson, Obamas towering body man and genial golf partner, took the call from his opposite number in the Romney camp, Garrett Jackson.

Obama retreated to a small dinette area. The party around him had reached such a crescendo that he had to plug a finger in his right ear to hear the familiar voice on the other end.

Hello, Mr. President, its Mitt Romney

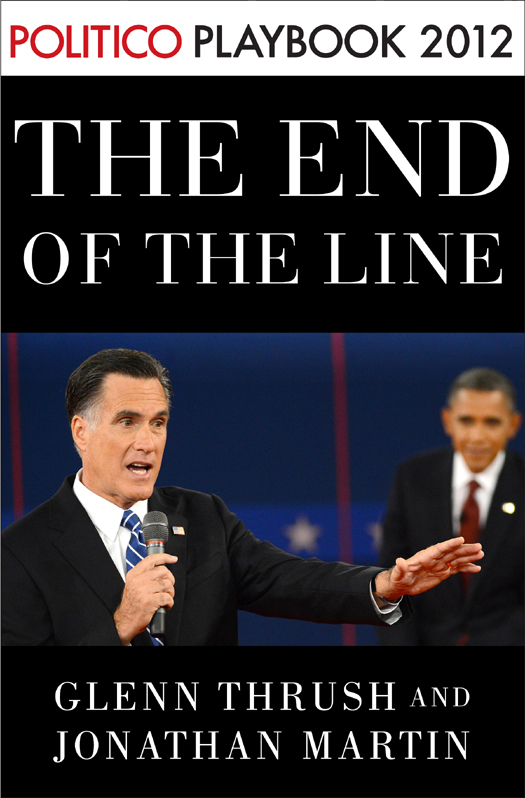

At 11:15 P.M. back east, in the Westin overlooking Boston Harbor, Romneys family and staff stood around white leather couches in a state of shock. Romney had been told hed likely lost, and his advance staff was setting in motion plans to concede.

It was an intensely painful scenario for a campaign that had been confident in victory hours before.

The television wasnt even turned on in Romneys room on the sixteenth floor.

Instead, he preferred to follow the returns through updates from his senior aides. Jackson would relay the latest states that had fallen from his iPhones Twitter feed. Rhoades shuttled in from the war room down the hall with fresh data. Some of it came from news organizations, some of it from Romney aides scrolling through websites with the election returns. The campaigns Election Day monitoring system, Orcawhich no one had apparently bothered to field-testwas basically useless.

Here was a fitting way to end a campaign marked by resilience and flashes of inspirationbut ultimately sunk by strategic ineptitude and a level of self-delusion breathtaking on a team that featured some of the brightest brains and hardest heads in the Republican Party.

Obama had drafted what his team jokingly called his loser speech with Favreau days earlier. Romney had written nothing, pretty sure he wouldnt need one.

What Mitt paid attention to was the enthusiasm of the crowds, the size of the crowd, because there was real momentum out there, said Spencer Zwick, his finance chief and family friend. I totally believed we were going to win, and I think everyone around him believed we were going to win. If anyone tells you that they knew we werent going to win, I think theyre lying to you.

His wife, Ann, was completely sold on her husbands impending victory. Were going to win this, she told an aide who had suggested the possibility of an alternative outcome the night before en route to a final rally in New Hampshire.

Now the end was coming, and far faster than anyone anticipated. When Rhoades revealed that Romney had lost Wisconsin and that their pathway was basically gone, the candidate responded in his typical matter-of-fact fashion. Time to get working on that concession speech, he said.

Romney, a boyish sixty-five, was realizing that the dream which had eluded his father, the Michigan governor and 1968 GOP hopeful, George Romney, was also beyond his reach. Still, he slipped easily into his accustomed role as family patriarch and church elder, betraying little emotion as he began hashing out his remarks.

Hes sitting there playing with his grandkids, as calm as he could be, recalled a source in the room.