Contents

Guide

FOR THE PEOPLE OF CHILE

Its as if Im pushing through massive mountains

through hard veins, like solitary ore;

and Im so deep that I can see no end

and no distance: everything became nearness

and all the nearness turned to stone.

Im still a novice in the realm of pain,

so this enormous darkness makes me small;

But if its You steel yourself, break in:

that your whole hand will grip me

and my whole scream will seize you.

Rainer Maria Rilke, The Book of Hours

CONTENTS

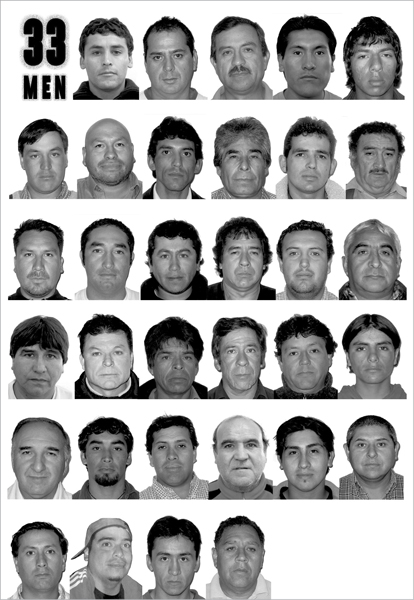

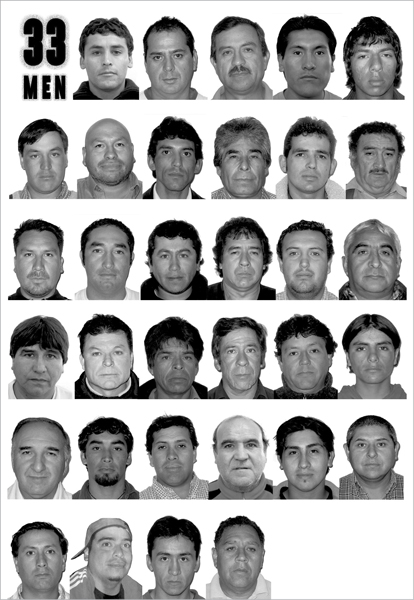

TOP ROW, FROM LEFT TO RIGHT: Florencio Avalos, Mario Seplveda, Juan Illanes, Carlos Mamani, Jimmy Snchez; ROW 2 : Osman Araya, Jos Ojeda, Claudio Yez, Mario Gmez, Alex Vega, Jorge Galleguillos; ROW 3 : Edison Pea, Carlos Barrios, Vctor Zamora, Vctor Segovia, Daniel Herrera, Omar Reygadas; ROW 4 : Esteban Rojas, Pablo Rojas, Daro Segovia, Yonni Barrios, Samuel Avalos, Carlos Bugueo; ROW 5 : Jos Henrquez, Renn Avalos, Claudio Acua, Franklin Lobos, Richard Villarroel, Juan Carlos Aguilar; ROW 6 : Ral Bustos, Pedro Cortez, Ariel Ticona, Luis Urza

PROLOGUE: CITIES IN THE DESERT

The San Jos Mine is located inside a round, rocky, and lifeless mountain in the Atacama Desert in Chile. Wind is slowly eroding the surface of the mountain into a fine, grayish orange powder that flows downhill and gathers in pools and dunes. The sky above the mine is azure and empty, allowing an unimpeded sun to bake the moisture from the soil. Only once every dozen years or so does a storm system worthy of the name sweep across the desert to drop rain on the San Jos property. The dust is then transformed into mud as thick as freshly poured concrete.

Few sightseers visit this corner of the Atacama, though the naturalist Charles Darwin did pass nearby, briefly, during his nineteenth-century journey around the world on a Royal Navy research vessel. The locals told him scientifically implausible stories that linked the rare rains to earthquakes. The vastness of Atacama and the absence of animal life surprised Darwin, and in his journal he described the desert as a barrier far worse than the most turbulent ocean. Even today, birders who pass through this part of Chile note that there are few if any avian species to be found. In the deeper desert, the only conspicuous living presence is of mining men, and the occasional woman, riding in trucks and minibuses to the mountains where there is gold, copper, and iron to be extracted.

The wealth of minerals under the barren hills draws workers to the Atacama mines from the nearby city of Copiap, and from many other distant corners of Chile. Juan Carlos Aguilar travels the farthest to reach the San Jos: more than a thousand miles. The shape of Chile on a map is that of a snake, and Aguilars trek to work takes him along half the snakes body. His weekly commute begins in the temperate rain forests of southern Chile. At the mine he supervises a team of three men who repair front loaders and the squat, long-armed, insect-like vehicles known as jumbos, during a seven-day shift that begins on Thursday morning. But his ride to work starts thirty-six hours earlier on Tuesday evening in the town of Los Lagos. No local job pays as well as his gig in the desert, so he settles his weary, middle-aged body into a Pullman bus, and watches as the shadows of beech forests, eucalyptus tree farms, and mountain rivers pass by his window. The weather matches his mood: The sky is overcast and raindrops beat on the windows, as they usually do when he sets out for work. The average precipitation in the region of Chile he calls home, at the 40th parallel of the Southern Hemisphere, is 102 inches a year.

One of the mechanics in the supervisors three-man crew lives somewhat closer to the mine. Ral Bustos leaves for work from the port city of Talcahuano, near the 37th parallel. A tsunami struck Talcahuano five months earlier, triggered by an 8.8 magnitude earthquake. The disaster killed more than five hundred people, left the city covered with pools of ocean water in which thousands of fish flopped about, and washed out the navy base where he used to work. Bustos is a punctilious father of two and devoted husband. He boards a bus heading northward, then travels along a flat landscape filled with greenhouses, tractors, and the fallow and cultivated fields of Chiles agricultural heartland. He passes through the town of Chilln, where another member of Aguilars crew begins his own journey northward, and then through Talca, where a tall and devoutly Christian jumbo operator boards yet another bus. The men who work inside the San Jos Mine are divided into two shifts, A and B, each working seven days at a time, and all these men have been assigned to the A shift. The A shift, in turn, is divided into twelve-hour-long night and day shifts that keep the mine working around the clock, from 8:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. to the following 8:00 a.m.

The commuting members of the A shift soon enter Santiago, with its under-construction skyscrapers and elevated roads. For the southerners, its early morning as they pull into Santiago, a booming Latin American capital whose most distinguishing feature, the massive and soaring silhouette of the nearby Andes, is often lost in the haze of the citys notorious smog.

In the intercity bus terminals in the center of Santiago, not far from Chiles presidential palace, more men set out for the San Jos Mine. One is Mario Seplveda, a frenetic father of two who has a reputation among his coworkers for pushing the front loader he operates too hard (thus forcing the mechanics to repair it repeatedly), and for talking too loud and too much, and for being generally unpredictable. On Wednesday afternoon he sets out on the five-hundred-mile journey from Santiago to the San Jos Mine later than he should: There is a fair chance he wont make it to work on time. Marios nickname at the San Jos is Perri, which is short for Perrito, the diminutive of the word perro , or dog. Ask Mario why hes called Perri and hell tell you its because he loves dogs (he owns two rescued strays at home), and because I have the heart of a dog. Like a dog, Mario is loyal, but if you try to hurt him, Ill bite you. He and his wife, Elvira, have two children, the first conceived in an impassioned encounter standing up, against a pole. Now they have a home on the fringes of Santiago where his prized possession is a big meat locker, and where Marios favorite place to sit is the small, square-shaped table in his living room. He enjoys a hurried meal at the table with Elvira and their teenage daughter, Scarlette, and their young son, Francisco, before leaving for the north.

After departing central Santiago, and then passing through the working-class suburbs on the citys northern fringe, the various buses carrying the men of the A shift enter valleys filled with vineyards and fruit trees, the snow-covered Andes of August winter on their right. The climate is Mediterranean, but the vista loses more of its greenness with each passing hour and with each latitude they cross: 33, 32, 31 south. Soon theyre entering the arid region called the Norte Chico, or Near North.

Mining men and other adventurers have traveled this route from the earliest days of Chilean history. The north is Chiles desert frontier, its Wild West. Its the place where the dictator Augusto Pinochet preferred to imprison his foes, gathering more than one thousand political dissidents in the living quarters of an abandoned saltpeter mine, where they passed the time studying astronomy underneath the pristine desert sky. Chiles union movement was born in the north, founded at the beginning of the twentieth century by nitrate miners who were later massacred in the city of Iquique, and in the democratic Chile of today much of the north still votes faithfully for the left. Pinochet also had the men and women he murdered buried in shallow graves in the desert, in the Norte Grande, or Far North, and their bones are still being discovered forty years later by relatives searching for the disappeared.