G.P. Putnams Sons New York

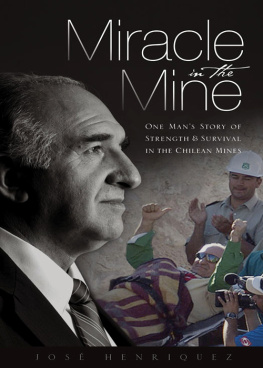

This book is dedicated to my family, who barely saw me for the duration of this dramatic tale: Toty, my ever patient and daredevil wife, and my six precious daughters, Francisca, Susan, Maciel, Kimberly, Amy and little Zoe. And finally to my grandson Tomas, who hardly saw me.

Writing this book was a challenge and a journey, not nearly as wrenching as that lived by the thirty-three miners, but I, too, am excited to finally be at home and at peace.

Jonathan Franklin

December 2010

Santiago, Chile

AUTHORS NOTE

A Word on Translation

Chilean Spanish is notoriously rich in slang. Miner lingo is notoriously rich in obscenities. The combination of those two realities made a literal translation virtually impossible. In many cases the Spanish used by miners and rescue workers, families and politicians has been translated to preserve the essence and meaning. Many obscenities have been simply removed not because of any particular offense, but due to the simple fact that they do not make sense in other languages. The author and publisher have maintained the intent of the words but allowed for a more coherent translation style. Given the use of multiple translators, there are likely to be minor differences of opinion in how best to present the rich texture of Chilean Spanish to a global audience.

A Word on Dates and Hours

This book is based on interviews with approximately 120 different participants in the rescue, including a majority of the miners, President Piera and leading designers and participants. Due to the extraordinary nature of their underground confinement and the monotony of confinement, the miners were not always able to confirm the exact time and date of certain events. With no daylight or darkness to mark the passage of time, such confusion is understandable.

The author has sought to make sense of this confusion and understands it well as he personally went for one eight-day stretch without changing clothes, showering or even taking off his boots. Fatigue and exhaustion were in abundant supply for the last twenty days of the rescue. The author wishes to stress that despite repeated efforts to clarify certain sequences, discrepancies continue to exist among the very participants. Such is the nature of dramatic events.

Exclusive Access

Many of the scenes and interviews in this book were not available to the thousands of journalists at Camp Hope. Early in the rescue effort I reported from behind the police lines like the other reporters. As I realized the scope and drama of the operation, I asked the Asociacin Chilena de Seguridad (ACHS), the insurance company in charge of much of the rescue operation, for permission to document their remarkable rescue efforts. I was covering the drama for numerous media including the Washington Post and The Guardian . The ACHS immediately agreed and provided me with a half-day tour of the rescue operation. They then told me the tour was over.

I asked to stay on and continue to report. In that case, I was told, I would need a Rescue Team credential. I filled out the forms, wrote that I was a writer and was given pass No. 204. For much of the ensuing six weeks I was able to roam the front rows of the rescue as I reported, recorded and filmed. At no time did I suggest that I was on any other mission than full-time reporter.

The Oakley Sunglasses

In accordance with full disclosure, I am proud to say that I was responsible for the miners receiving Oakley sunglasses. During a planning meeting between Codelco and the Chilean Navy early in September, it became apparent that the miners needed high-quality eyewear upon leaving the mine. Given the overwhelming logistics of planning the rescue, the officials were swamped with tasks and a bit lost on what to do about sunglasses. Seven years earlier, I had met Erik Poston, an Oakley representative. I still had his business card. I wrote Oakley an email suggesting they send thirty-five pairs of sunglasses (two spares) to the Chilean rescue team. They complied and the rest is history.

Acknowledgments

In writing this book in the immediate aftermath of the mining drama, I found the challenges were numerous, the sacrifices many. First I would like to thank my wife, Toty Garfe, for accepting my months-long disappearing act. And to my daughters Kimberly and Amy, sorry to have missed your birthday. Zoe, your baptism photos are great; it would have been better to have been there. Susan, congratulations on winning so many high-diving medals; I saw the video. Maciel, how did you grow half a foot in two months? Francisca, my first daughter, your loyalty to your globe-trotting dad is appreciated.

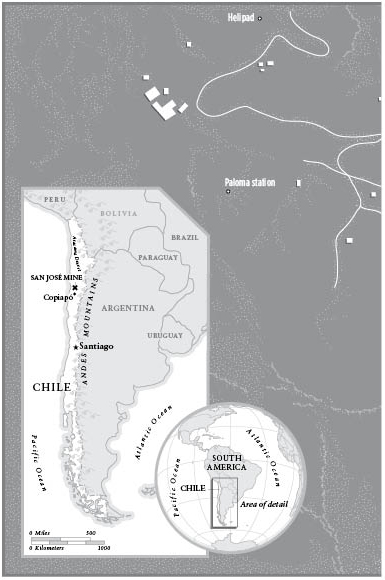

To Annabel Merullo, Caroline Michel, Juliet Mushens, Alexandra Cliff and the team at PFD, you were the first to see the potential of this book and guided it through the Frankfurt Book Fair and to higher ground. I am forever grateful. George Lucas of Inkwell Management, you guided this book through the jungles of U.S. publishing and landed me at Putnam, where Marysue Rucci and Marilyn Ducksworth were instrumental in turning this book into a beautifully designed, finely edited and nationally known work. Both Diana Lulek and Michelle Malonzo at Putnam dropped their schedules to answer my many questions about publishing my first book. At Putnam I would also like to thank the managing editorial team of Meredith Dros and Lisa DAgostino, who were busier than air traffic control at JFK, keeping all the pieces of this project in sync. And to Putnam President Ivan Held for his backing of my first book: I appreciate your unwavering support. Finally, I want to thank Art Director Claire Vaccaro, who patiently figured out the maps and photos, and Copy Chief Linda Rosenberg, who worked through the holidays. To Bill Scott-Kerr and Simon Thorogood at Transworld Publishing in London, your early support for this project was key to making it happen. Bob Bookman and the team at CAA for everlasting optimism inside the madness that is Hollywood movie production. To Colin Baden, Diane Thibert, and Rachel Mooers at Oakley for a generous contribution to the miners. Thanks to Martn Fruns, Alejandro Pio and the entire medical and psychological staff at the ACHS for their professional treatment and constant help throughout this project. A special mention of psychologist Alberto Iturra, who may have had the hardest job of allkeeping the miners united underground. Alberto, the miners may not have realized how hard your job was, but the rest of us did!