Table of Contents

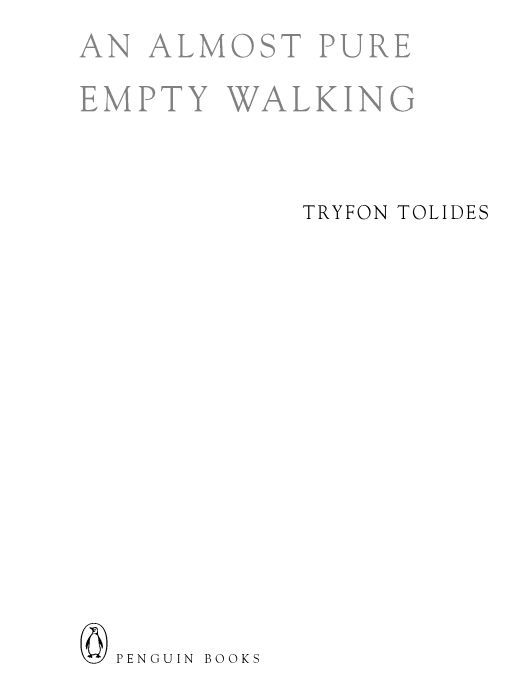

PENGUIN BOOKS

AN ALMOST PURE EMPTY WALKING

TRYFON TOLIDES was born in Korifi Voiou, Greece. He lives and writes in Farmington, Connecticut. He has completed a BFA in Creative Writing at the University of Maine, and a MFA at Syracuse University. He had received a Reynolds Scholarship and the 2004 Foley Poetry Prize.

THE NATIONAL POETRY SERIES

The National Poetry Series was established in 1978 to ensure the publication of five poetry books annually through participating publishers. Publication is funded by the Lannan Foundation; the late James A. Michener and Edward J. Piszek through the Copernicus Society of America; Stephen Graham; International Institute of Modern Letters; Joyce & Seward Johnson Foundation; Juliet Lea Hillman Simonds Foundation; Tiny Tiger Foundation; and, Charles B. Wright III. This project also is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts, which believes that a great nation deserves great art.

2005 COMPETITION WINNERS

Steve Gehrke of Columbia, Missouri,Michelangelos Seizure

Chosen by T. R. Hummer, to be published by University of Illinois Press

Nadine Meyer of Columbia, Missouri,The Anatomy Theater

Chosen by John Koethe, to be published by HarperCollins Publishers

Patricia Smith of Tarrytown, New York,Teahouse of the Almighty

Chosen by Edward Sanders, to be published by Coffee House Press

S. A. Stepanek of West Chicago, Illinois,Three, Breathing

Chosen by Mary Ruefle, to be published by Verse Press/Wave Books

Tryfon Tolides of Farmington, Connecticut,An Almost Pure Empty Walking

Chosen by Mary Karr, to be published by Penguin Books

Copyright page

(TK)

For the memory of my parents:

PANAGIOTI AND ZOI

And for my brother:

DEMETRI

A little farther

we will see the almond trees blossoming

the marble gleaming in the sun

the sea breaking into waves

a little farther,

let us rise a little higher

GEORGE SEFERIS, FROM Mythistorema

(TRANSLATED BY EDMUND KEELEY

AND PHILIP SHERRARD)

They were those from the wilderness of stars...

WALLACE STEVENS

IMMIGRANT

My mother called this morning, kept trailing away,

or off, with complaints about her failure

to make it, alone in the house, the night being

long, no one to talk to, blaming, in part, America,

hating the mess weve found, or made this year.

What is America? she said. A hole in the water.

What have we gained but poison and illness?

Her whole message, a cry, though still she asked

what I would eat for lunch. Back in bed,

I listened awhile to the furnace. Then, dressed,

passed the same books and papers spread on the floor,

and out, to the snow, the crows in the park.

ALMOND TREE

I miss smashing the green-covered shells,

peeling the bitter skin, putting the slippery seed

on my tongue.

I miss the outhouse. I miss the wind blowing

through the hole in the floor.

I miss the small door to the fallen balcony

and the swallows nests and their tunnels

stuck to the stone.

I miss the smell of fried eggs, potatoes, and cheese.

I miss the wood-paneled radio with the voices

from Tirane and Skopje.

I miss the dogs at midnight and the church gates

and the steep forest behind the cemetery.

I miss the bundles of tree limbs, the crackling fires,

the crazy bright fields of tan and clover.

I miss going down hills on wood sleds

made from old chairs, greased with pig lard.

I miss the barbed wire fence around the orchard

and climbing the cherry trees and watching ants

on the bark and flicking them off my fingers.

I miss the spring water. I miss the plug to the tap

to the spring water, the cloth and wood.

I miss the walk to the spring. I miss the black sky.

I miss the ghosts in the holy air.

CIRCUS

Once, when I was little,

some gypsies came to the village.

It was a hot Aegean rock-burning sun,

a hot dry fields-on-fire day.

The road was dust at midnoon

while iron bars latched shutters, and people slept

and bees and flies patrolled the flowers

and lizards spat underneath slate

and winds stirred waves of weeds

across the cemetery.

The gypsies would pass through like comets,

restrapping old chairs, selling embroidered

tablecloths, fine rugs, fresh fruit.

The tented pickup made its way

through neighborhood narrows and hands and offers,

and village women in pocketed aprons would emerge

from their houses, as if for the first time,

curious and shy, suspicious, welcoming.

Our mothers sometimes threatened

to give us to the gypsies,

who would bundle us away in their silk bolts

to the distant bazaars,

to sell us in streets, under canopies.

The heat grew like vines that day,

and in a short grass field, bangles of gypsy women

in veils with gold-toothed smiles,

and kicks that spun the earth on its side.

Clarinets and big skin drums played,

and sweat was the shine on faces,

and cats made for the shadow of the quince tree

when suddenly, the circles collapsed into a crowd,

and cheer evaporated,

and voices silenced above a fainted gypsy man.

Someone disappeared toward the well,

and God returned him quickly,

with a pail of water.

Then the gypsys eyes splashed open,

and cracks of laughter resprung along the hillsides,

and the bare feet of gypsy children resumed their dance,

the air filled with the deep boom of drums.

THE FIRST THING: OUSIA

At first, it is one thing. Insignificant and supreme. The first thing.

You develop ways around it. Never solve it. It becomes part of you.

Years pass. Another thing comes. You think: if only I can solve

this new thing, if it will only go away, because the first has become

livable somewhat, with held breaths, and luck (though, truly, you dont

want to have the first thing, because it remains dangerous).

But by the time you think it through, the new thing becomes part

of your nerves. Then, more things pile up. And so, more held breaths,

more luck hoped for. You try to find value in it. In my village,

they say certain pears are best eaten after theyve fallen to the ground

and been there a few days, their bruises grown. The fruit attains its fullest

flavor then, just as with certain soups, you have to suck the bones

of their marrow to get the ousia, the essence, the best part.

ETYMOLOGICAL

The word cancer was like a candy wrapper

from a country Id almost heard of.

Karkinos in Greek. Close to kokkinos,

red. The k makes the crust and scab of the word.

The r the rich tube-like liquid,

possibly to ooze or stain or bulge. In the clinic

above the busy intersection in Thessaloniki.

My Uncle Apostolos bed

was white. What I remember of the word cancer

when the dark of it first dissolved into being:

the metal bed frame was painted white

and round above his head. The sheets had some red

toward his feet, near his stomach. I looked at his face