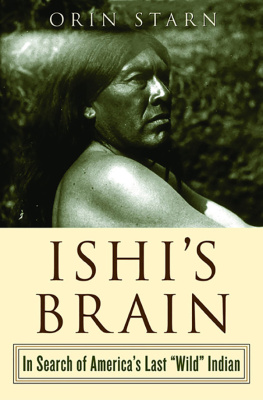

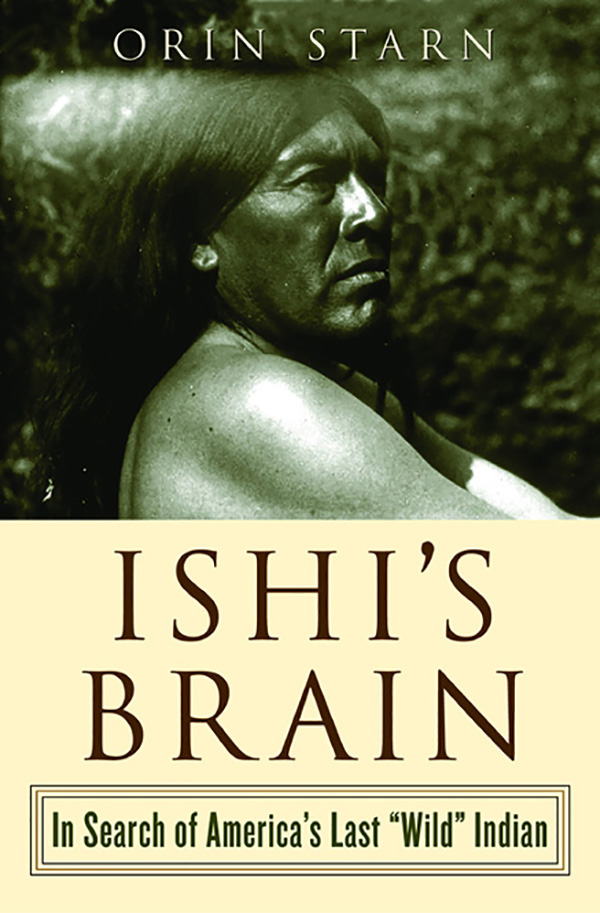

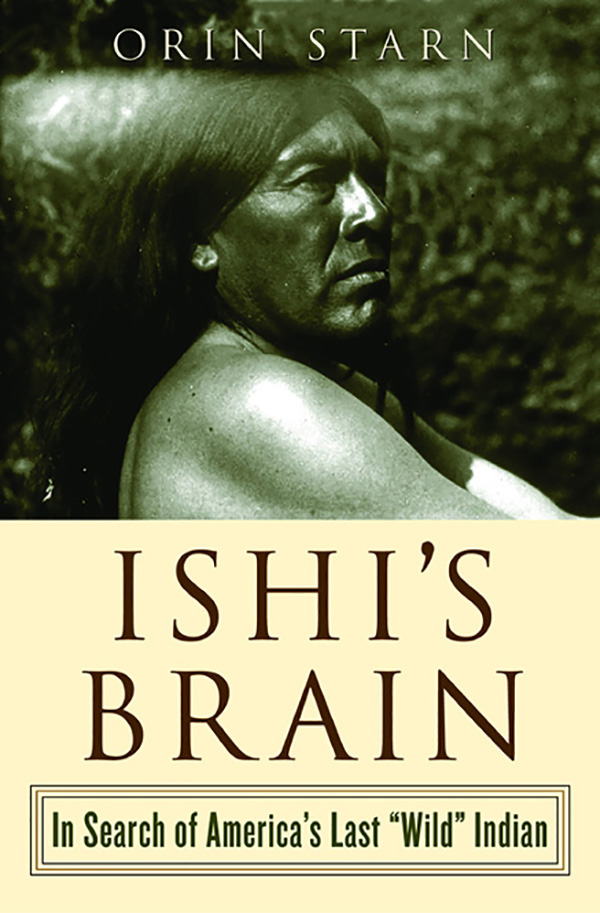

Copyright 2004 by Orin Starn

When I Have Donned My Crest of Stars from Kiliwa Texts by Mauricio Mixco (University

of Utah Anthropological Papers 107 [1983]) is reprinted by permission of the University of

Utah Press. Half-Indian/Half-Mexican by James Luna reprinted by permission of

James Luna and News from Native California.

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

Book design by BTDnyc

Production manager: Julia Druskin

The Library of Congress has catalogued the print edition as follows:

Starn, Orin.

Ishis brain : in search of Americas last wild Indian / Orin Starn.1st ed.

p. c.m.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-393-05133-1 (hardcover)

1. Ishi, d. 1916. 2. Yana IndiansBiography. 3. Yana IndiansAnthropometry. 4. Kroeber,

A. L. (Alfred Louis), 18761960Relations with Yana Indians. 5. Kroeber, Theodora

Relations with Yana Indians. 6. Human remains (Archaeology)RepatriationUnited

States. 7. Human remains (Archaeology)Moral and ethical aspectsUnited States.

8. Cultural propertyRepatriationUnited States. I. Title.

E99.Y23 .I785 2004

979.4004'9757dc22

20030201066

ISBN 978-0-393-32698-7 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-393-29307-4 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

TO ROBIN

and the memory of Rosalie Bertram, wenem kuhlah

CONTENTS

I S H IS B R A I N

I grew up in the sixties just across the bay from San Francisco in the university town of Berkeley. Our house was down the street from the abandoned campus parking lot that activists commandeered in 1969 for Peoples Park, the Elysian Fields of Berkeleys counterculture and the meeting point for protest marches against the Vietnam War. My dovish parents dragged me to the biggest rallies, but I also had to take violin lessons, even ballroom dancing class up in the Berkeley hills. Great was my adolescent relief when the tear gas drifting down from Peoples Park meant my mother could not drive me to the year-end luau, for which Id been garbed in the requisite flowery Hawaiian shirt. Later that week, the riot police shot down a rock-throwing protester on nearby Telegraph Avenue.

The peace marches, tear gas, and police helicopters form part of my Berkeley memoriestogether with baseball cards, slingshot practice, and trolling for crawdads with hotdogs on a string at Lake Temescal. And like so many American kids, before and after that turbulent time, I was fascinated by Indians. My early interest was of a very traditional Middle American variety, fostered in a YMCA summer camp where we practiced archery, received a secret Indian name, and made beaded wampum for our parents. I was not old enough to want to try peyote or go off to live in some vegetarian communes tepee. At this time in Berkeley, however, a young generation of hippies and radicals was enshrining Native Americans as icons of countercultural spirituality and community, even as inspirations to rebellion. One leaflet explaining the takeover of Peoples Park featured a picture of a resolute Geronimo with his rifle. That the protest leaders were white did not stop them from acting in the name of the Apache chief and the spirit of the Costanoan Indians who had once roamed the East Bays marshlands.

Im not sure just when I first heard about Ishi. Then, as now, every California fourth grader learns the well-known story of this last wild Indian in North America. Along with a few other holdouts from his tiny Yahi tribe, Ishi had hidden out in the hills above the Sacramento Valley for more than fifty years. The others died, and Ishi was captured in 1911, then brought to stay in a San Francisco museum. Since my father was a historian of the Italian Renaissance, we lived in Italy for several years and I went to fourth grade in a town near Florence. There we were taught about Garibaldi and the Risorgimento, not American Indiansthe pelle rossi, as the Italians knew them from spaghetti Westerns. I do remembersometime later and back in the United Statesbeing taken to Kroeber Hall on the Berkeley campus, named after the famous anthropologist who became Ishis main guardian in San Francisco. One corner of Kroeber Halls exhibition space was devoted to Ishi. It included arrowheads that Ishi had made at the museum, among them one fashioned from the royal blue glass of a Phillips Milk of Magnesia bottle. I was mesmerized by the perfect symmetry and form of these objectsand the idea of heading off to the hunt with a real bow you had made yourself.

A trip to a friends family summer cabin took me near Ishis country for the first time when I was in junior high. The cabin was an A-frame in a vacation development behind Mount Lassen, close to a reservoir packed with waterskiers and houseboats. It was six hours from Berkeley, and the last part of the drive wound over the mountains by Highway 32, which runs for a time next to the black boulders, powerful rapids, and deep emerald pools of Deer Creek. This stretch of road is many miles upstream from the territory once inhabited by Ishi and the last Yahi survivors. Blissfully ignorant of this fact, I was busy imagining a long-ago Ishi spearing salmon in the streams shimmering wateror maybe even some as yet undiscovered tribesman at that very moment monitoring the slow progress of our giant fake-wood paneled station wagon from his secret lookout in the cliffs above. Ishi and his people held the same mystique for my friend as they did for me. As a tribute a few years later, he posed himself for his individual high school yearbook picture, standing next to Deer Creek clad only in an imitation Yahi breechcloth.

As a judgmental teenager, I had no interest in a professors life. I found my parents Berkeley faculty world of lectures and dinner parties stuffy and artificial. In 1981, I left college and headed off with a friend to the Navajo Reservation in a decrepit VW bug. The principal at Shiprock Alternative High School, a pony-tailed Navajo poet and educator, looked bemused at the sight of a pair of white nineteen-year-olds appearing out of the desert to offer themselves as volunteers in his school. After he called our parents to make sure we were not runaways, it was finally agreed that we could sleep on mattresses in an abandoned storeroom. I lived in that storeroom for the next year.

I was the quintessential young bleeding-heart idealist, of course, the latest in that wave of missionaries, aid workers, and others whod come to help the Indians in the blasted-out, impoverished town of Shiprock. Still, with the modest enough purpose of making myself useful at the school, I tried to avoid coming across as a suck-up or a savior. My main duties were to assist the schools two cooks and janitor, all of whom were glad enough for an extra hand. You better clean that toilet really good, Mary Kehane, the old Navajo janitor, liked to tell me. One of the cooks, Jeanette, was Hopi. As we prepared lunch, she and Faye, the Navajo cook, sparred over the radio tuned loud to their favorite country music station. Hopis dont even know how to peel potatoes, Faye would taunt Jeanette. And you neither, bilagana, shed grin in my direction, employing the Navajo word for white man.

If drawn to Indians, I knew little about them when I went off to Navajoland. Id gone to Berkeleys integrated schools with whites, blacks, Japanese Americans, and the children of Vietnamese boat people, but Id never met an Indian in the flesh, at least as far as I knew. Along with the vague idea of reservation poverty, my exposure was limited to the mish-mash of myth and stereotype offered up by Hollywood and popular culturethe bloodthirsty redskins who roasted a captured soldier alive on a spit in a grisly Western I saw as a child; the slender, Pocahontas-like Indian princess on the package of the Land OLakes butter with which we spread our Sunday morning pancakes; and, of course, Ishi, alone in the canyon of Deer Creek as the world closed in around him. So pervasive have these images become of a vanished or vanishing people of the wigwam, the war bonnet, and the buffalo that some Americans still do not know quite what to make of the real thing. A young Creek friend of mine still laughs about her first meeting with her freshman college roommate. Do you live in a tepee? the wide-eyed girl had asked. Kelly, the daughter of a schoolteacher and a businessman, explained that shed grown up in a comfortable English Tudor-style house in her hometown of Atmore, Alabama.

Next page