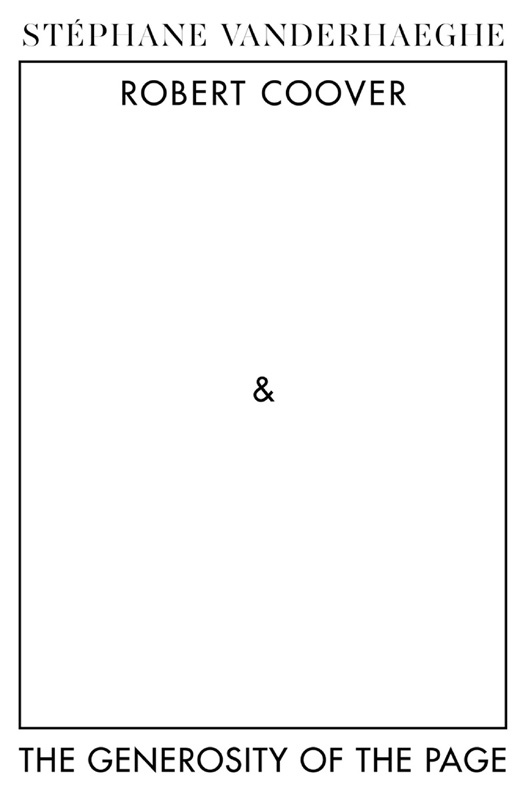

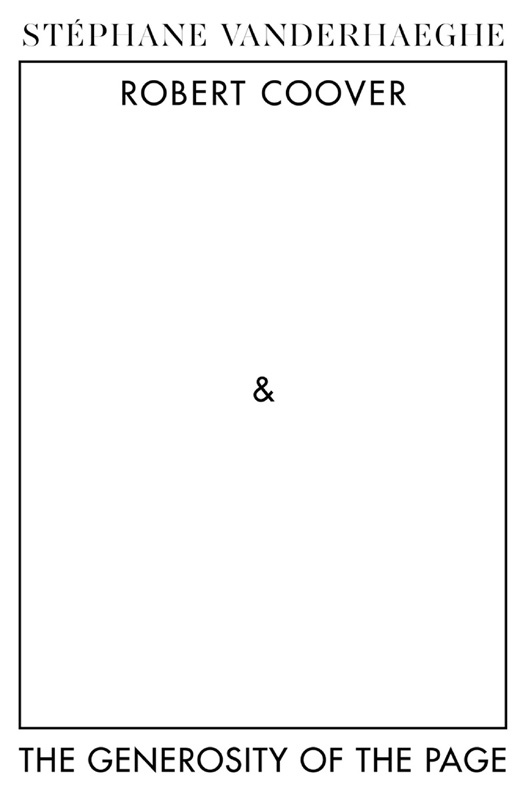

Robert

Coover

-&

the

Generosity

of the Page

Stphane

Vanderhaeghe

He began a parody on Platos cave parable, in which he celebrated, not the shadows, but the generosity of the wall.

In Bed One Night & Other Brief Encounters

for all the kapoos between the lines of my world

Contents

_____________You mean these first words and lines to be both decisive and incisive for it is here, in and with them, that the reading process is supposed to begin; here, upon the blankness of a page generous enough to offer itself to the critical act, those first words and lines somehow have to carve, the better to separate themselvesthe act itself maybe nothing more than a literary putschfrom the texts they build upon, in all confidence of their power, of their progress chapter after chapter towards the programmatic end the text they compose would undeviously lead to, all the way over there, somewhere down at the bottom of a page forever blackened in advance. But that would be taking no heed of what some refer to when they claim that reading is anguish, an anguish from which, ultimately, there is no escaping: a text, they say, any text, however important, or amusing, or interesting it may be (and the more engaging it seems to be), is emptyat bottom it does not exist; you have to cross an abyss, and if you do not jump, you do not comprehend. Putsch, you said? How then claim any right over what, at bottom, does not exist? How then distance yourself from what you are already kept aloof, over here, in the sidelines or marginson the other side of the abyss you still have to cross?

But, you say, what choice is there when one must build upon the texts? Linkage must happen and must happen now, for another phrase cannot not happen. It is a necessity; time, that is. The texts themselves require it, demand it in a way, for even the silence they all too often leave you with when the book closes is a phrase that, in the end, makes it all too apparent that there is no last phrase. When the reading process is supposed to begin, here, now, with those first words and lines of yours, the texts they build upon are merely left in abeyance and are in no way over with their writing yet; for you know, you do, that these texts keep shaping the void and silence that inhabit them. Criticism, despite all its pretenses, can never fully detach and separate itself from the texts it aims to comment upon; you even fear, on the contrary, that it might encroach upon them, feeding off them like a parasite. And while the texts, you realize, are provisionally left in abeyance, the critical act you profess unavoidably is closing them down upon themselves at the very moment it decisively incises the page, blank no longer, to inscribe those first words and lines; criticism summons and sums them uprounds and shuts them up, you sometimes thinkin a so-called thesis it seeks to formulate, all too confident in its own power and progress from those first few words and lines to the last that in the long run must logically follow upon them, ordered as you would like your language to be, by and on the authority of some chapter or other at the head of each new squadron of thought you deploy. This way you know your reading will proceed in an orderly fashion, as it should, authoritatively and properlyno deletion whatsoever, no erasure, no impropriety. But you suspect that if this is so, reading proper has long capitulated and can only, incessantly, recapitulate. Yet again.

Incisive and decisive though you wish they had been, those words and lines were notcould not bethe first ones, and it is notcannot bein and with them that the reading process begins; as if there were a beginning of reading anyway, as if everything were not already read, one way or another: there is no first reading in the same way that, there being ultimately no last phrase, there can be no first word or line: nothing you will and can say comes first, everything is handed down to you second-hand. No beginning then, you decide, no chapters either: and yet, already, words and lines are being linked, explanation after justification; an army of thought is already underway as phrases occur that exclude others, channeled as they are towards an inevitable end, all the way down there, somewhere at the bottom of a page, at the end of a line, like the long-awaited punchline from which, as though backwards, your set-up text would have taken its cue. These first words and lines that no longer are and never have been, have nonetheless started to exhaust the range of possibilities generously opened by the texts; facing a dead end, you have no other choice but to turn around; you waver on the edge of the abyss and you know you have to cross itnow; it is a necessity...

The best, you think, would have been not to have to begin. But I have to begin, you remind yourself. That is to say you have to go on, building upon and linking onto the words of others. Go on, then, link on, since you must... Those few first words and lines of yours that never were, have at least gained, you hope, this meager merit: in and with them, you have begun inscribing your reading when you found it difficult to do so; or ratherfor you know betterthose few words and lines have, for you, begun feigning to translate your reading into words, into a writing of sorts, because it was impossible not to do so; you lift one foot tentatively above the abyss, ready to advance and let go, albeit timidly, usurping the beginning in the meantime, displacing it, deferring it; yes, an unbeginning of sorts, you muse, so that when in the end your reading begins, or seems to, you know there could be no other option left but to begin anew, starting it all over again______________________

... the disciples consciousness, when he begins,

He must be right. I began at the beginning, like an old ballocks, can you imagine that?

I would not say to dispute, but to engage in dialogue with the master or, better, to articulate the interminable and silent dialogue which made him into a disciplethis disciples consciousness is an unhappy consciousness.

Heres my beginning.

Starting to enter into dialogue in the world, that is, starting to answer back,

Because theyre keeping it apparently.

he always feels caught in the act, like the infant who, by definition and as his name indicates, cannot speak

I took a lot of trouble with it.

and above all must not answer back. And when, as is the case here, the dialogue is in danger of being takenincorrectlyas a challenge, the disciple knows that he alone finds himself already challenged by the masters voice within him that precedes his own.

Here it is.

He finds himself indefinitely challenged,

It gave me a lot of trouble.

or rejected, or accused; as a disciple, he is challenged by the master who speaks within him and before him, to reproach him for making this challenge and to reject it in advance, having elaborated it before him; and having interiorized the master, he is also challenged by the disciple that he himself is. This interminable

It was the beginning, do you understand?

unhappiness of the disciple perhaps stems from the fact that he does not yet knowor is still concealing from himselfthat the master, like real life, may always be absent.

Next page