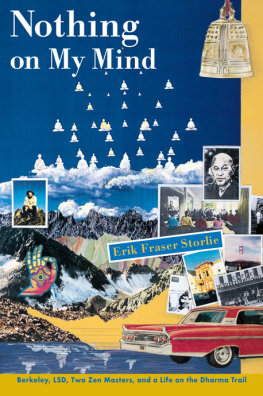

ABOUT THE BOOK

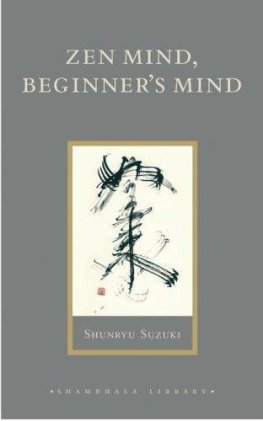

This frank account by a longtime Zen student looks back over a journey that began in Berkeley in the heady sixties when the author experimented with psychedelics and started to study with Suzuki Roshi, who encouraged his students to find a genuine way of practicing Zen.

ERIK FRASER STORLIE has been a student of Zen for almost thirty years and was one of the founders of the Minnesota Zen Mediation Center in Minneapolis. He teaches English and humanities at Minneapolis Community College.

Sign up to receive weekly Zen teachings and special offers from Shambhala Publications.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/ezenquotes.

SHAMBHALA PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

1996 by Erik Fraser Storlie

Cover art by Emily Betsch. Photographs by Nacio Jan Brown, Erik Fraser Storlie, Chellis Glendinning, Robert Boni, and Paul Turner. Drawing of mudra by Arthur Okamura.

The poem by Rumi on the following page is from Open Secret: Versions of Rumi, translated by John Moyne and Coleman Barks (Threshold Books, RD 4, Box 600, Putney, Vermont 05346), reprinted with permission. The material from The Psychedelic Experience (A Citadel Press Book, copyright 1964 by Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner, and Richard Alpert) is published by arrangement with Carol Publishing Group.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Storlie, Erik.

Nothing on my mind: an intimate account of American Zen/ Erik Storlie.1st ed.

p. cm.

eISBN 978-0-8348-0006-9

ISBN 1-57062-183-7 (alk. paper)

1. Zen BuddhismUnited States. 2. Spiritual lifeZen Buddhism. 3. Storlie, Erik. I. Title.

BQ9262.9.U6S76 1996 96-16432

294.3927092dc20 CIP

[B]

BVG 01

When even just one person, at one time, sits in zazen, he becomes, imperceptibly, one with each and all of the myriad things, and permeates completely all time, so that within the limitless universe, throughout past, future, and present, he is performing the eternal and ceaseless work of guiding beings to enlightenment.... This is not limited to the practice of sitting alone; the sound that issues from the striking of emptiness is an endless and wondrous voice that resounds before and after the fall of the hammer.

DOGEN, Bendowa

We are the mirror as well as the face in it.

We are tasting the taste this minute

of eternity. We are pain

and what cures pain. We are

the sweet, cold water and the jar that pours.

RUMI

I play my song eating, eating the peyote, waiting to see the flower, the beautiful flower in the center there of the fire. I play to the four winds, offering all my will, all my affections, all my strength. I went to bathe in the sea, to learn how to sing, to learn how to play. Waves come and go, waves come and go. I ate of them. I ate the foam. Who now knows better how to sing? Who now knows better how to play? I ate the foam of the sea, the pure foam of the sea.

What does one see in the fire? You do not speak of it, not to the companions, not to you, not to anyone does one reveal what one has seen. One makes a garland of peyote to hang on the horns of the deer, of our elder brother.

Songs sung during the Huichol Indian peyote quest

Dainin Katagiri Roshi,

Teacher

And dear friend,

Wherever you wander

Or dont wander,

Know that this is for you.

IF READERS ARE CURIOUS ABOUT THE MAKING OF this book, I should tell them it is not fiction, nor is it quite fact. All the incidents described happened to me. But it is memorymemory of events that go back over thirty yearsand memory in the service of a narrative.

In the first half of the book, the Berkeley half, I have freely telescoped or expanded events and, at times, drawn together traits of several people I knew and placed them in one character. Or placed the traits of one person in several. No actual names have been used. I sincerely beg pardon of all old friends and acquaintances who find here fragments of themselves. Please forgive these liberties. No offense is intended.

In the second half, the zen half, I have not altered events and people in this way. My experiences with Suzuki Roshi and Katagiri Roshi I have described to the best of my ability and memory. I have, nonetheless, reconstructed situations and conversations that I could not remember in precise detail. Occasionally I have gathered trenchant remarks that I remember from over the years into one place. The reader whose first purpose is to study these two zen masters must read with the knowledge that everything here is filtered through my memoryand through my follies, weaknesses, and attachments. The names given in this latter half are real.

I hope this book will encourage American forms of meditation practiceforms freed from the trappings of any specific culture, whether of a Japan or a Tibet or an India. This is a delicate matter, but I look for an American practice that does not forget our own ancestors: the Native American living in intimacy with the earth, the Puritan fiercely devoted to God, the Transcendentalist seeking spirit in all things, the African-American transforming and transmuting Christianity. The East gives us the Sanskrit dhyana, the Chinese chan, the Japanese zenupright sitting in firm, awake, one-pointed awareness. What American form can array this miraculous consciousness with which all are gifted?

I want to thank some of those friends who, in helping with this writing, have helped me weave together two painfully separated strands of my life: the student, teacher, and lover of words in the tradition of the Greeksand the student of the wordless. I owe a great debt to William E. Coles. Bill was my instructor in Freshman English when I was seventeen and he, only several years older, the youngest member of the English Department at the University of Minnesota. Since then, he has ever pressed me to write good English. About ten years ago he gave me a method for doing my writing. Over scores of telephone calls, it has led to this book. The method is pure zen.

I also thank Robert Bly. He read and criticized the book and made valuable suggestions. More important, at many of the Minnesota Fall Mens Conferences and other gatherings, he has helped modulate my prairie Norwegian, Zen Buddhist way of being. His gift is the companionship of other men with dance, drum, song, and spirita taste of the joy that in more dour traditions must wait until death.

I am grateful to Robert Pirsig. He read the book, made valuable comments, and offered encouragement. His Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance and Lila were and are inspirations to write about the movement of Eastern modes of consciousness into America.

My agent Scott Edelstein has been solidly behind this project. In his readings and re-readings, he has been midwife. My editor Peter Turner has offered quiet, perceptive, and firm criticism. Edward M. Griffin read an early draft and told me things I did not want, but needed, to hear. Alan Trachtenberg was kind enough to read, comment, and encourage. Shohaku Okumura Sensei gave valuable advice on the English wording of a key Dogen passage and, most important, further instruction in zazen.

Next page