Also by David Chadwick

Thank You and OK!: An American Zen Failure in Japan

BROADWAY

A hardcover edition of this book was published in 1999 by Broadway Books.

CROOKED CUCUMBER . Copyright 1999 by David Chadwick. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. For information, address Broadway Books, a division of Random House, Inc., 1540 Broadway, New York, NY 10036.

BROADWAY BOOKS and its logo, a letter B bisected on the diagonal, are trademarks of Broadway Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Chadwick, David, 1945

Crooked cucumber: the life and Zen teaching of Shunryu Suzuki / David Chadwick,

p. cm.

1. Suzuki, Shunry u , 19041971. 2. Priests, ZenJapanBiography. 3. Priests, ZenUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

BQ 988. U 9 C 47 1999

294.3927092dc21

[b] 9846707

CIP

eISBN: 978-0-307-76869-8

Visit the website www.cuke.com

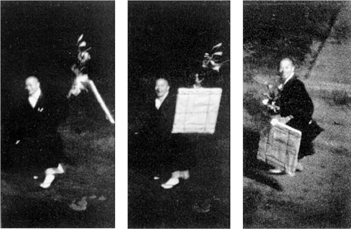

Sequence of photos on : Shunryu Suzuki at Haneda Airport, Tokyo, departing for America on May 21, 1959.

v3.1

To Shogaku Shunryu Suzuki-roshi

and all sentient beings,

wisdom seeking wisdom.

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

W ALT W HITMAN from Song of Myself

Introduction

T he teaching must not be stock words or stale stories but must be always kept fresh. That is real teaching.

O NE NIGHT in February of 1968, I sat among fifty black-robed fellow students, mostly young Americans, at Zen Mountain Center, Tassajara Springs, ten miles inland from Big Sur, California, deep in the mountain wilderness. The kerosene lamplight illuminated our breath in the winter air of the unheated room.

Before us the founder of the first Zen Buddhist monastery in the Western Hemisphere, Shunryu Suzuki-roshi, had concluded a lecture from his seat on the altar platform. Thank you very much, he said softly, with a genuine feeling of gratitude. He took a sip of water, cleared his throat, and looked around at his students. Is there some question? he asked, just loud enough to be heard above the sound of the creek gushing by in the darkness outside.

I bowed, hands together, and caught his eye.

Hai? he said, meaning yes.

Suzuki-roshi, Ive been listening to your lectures for years, I said, and I really love them, and theyre very inspiring, and I know that what youre talking about is actually very clear and simple. But I must admit I just dont understand. I love it, but I feel like I could listen to you for a thousand years and still not get it. Could you just please put it in a nutshell? Can you reduce Buddhism to one phrase?

Everyone laughed. He laughed. What a ludicrous question. I dont think any of us expected him to answer it. He was not a man you could pin down, and he didnt like to give his students something definite to cling to. He had often said not to have some idea of what Buddhism was.

But Suzuki did answer. He looked at me and said, Everything changes. Then he asked for another question.

S HUNRYU S UZUKI was a Japanese priest in the Soto school of Zen who came to San Francisco in 1959 to minister to a small Japanese-American congregation. He came with no plan, but with the confidence that some Westerners would embrace the essential practice of Buddhism as he had learned it from his teachers. He had a way with thingsplants, rocks, robes, furniture, walking, sittingthat gave a hint of how to be comfortable in the world. He had a way with people that drew them to him, a way with words that made people listen, a genius that seemed to work especially in America and especially in English.

Zen Mind, Beginners Mind, a skillfully edited compilation of his lectures published in 1970, has sold over a million copies in a dozen languages. Its a reflection of where Suzuki put his passion: in the ongoing practice of Zen with others. He did not wish to be remembered or to have anything named after him. He wanted to pass on what he had learned to others, and he hoped that they in turn would help to invigorate Buddhism in America and reinvigorate it in Japan.

B UDDHIST IDEAS had been infiltrating American thought since the days of the Transcendentalism of Emerson and Thoreau. At the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893, Soen Shaku turned heads when he made the first public presentation of Zen to the West. His disciple and translator, D. T. Suzuki, became a great bridge from the East, teaching at Harvard and Columbia, and publishing dozens of widely read books on Buddhism in English. When confused with D. T. Suzuki, Shunryu Suzuki would say, No, hes the big Suzuki, Im the little Suzuki.

The first small groups to study and meditate gathered with Shigetsu Sasaki on the East Coast and Nyogen Senzaki on the west. Books informed by Buddhism by Hermann Hesse, Ezra Pound, and the Beat writers were discussed in the coffeehouses of New York and San Francisco and by college kids in Ohio and Texas. Alan Watts, the brilliant communicator, further enthused and informed a generation that hungered for new directions.

Into this scene walked Shunryu Suzuki, who embodied and exemplified what had been for Westerners an almost entirely intellectual interest. He brought with him a focus on daily zazen, Zen meditation, and what he called practice: zazen extending into all activity. He had a fresh approach to living and talking about life, enormous energy, formidable presence, an infectious sense of humor, and a dash of mischief.

From the time he was a new monk at age thirteen, Suzukis master, Gyokujun So-on Suzuki, called him Crooked Cucumber. Crooked cucumbers were useless: farmers would compost them; children would use them for batting practice. So-on told Suzuki he felt sorry for him, because he would never have any good disciples. For a long time it looked as though So-on was right. Then Crooked Cucumber fulfilled a lifelong dream. He came to America, where he had many students and died in the full bloom of what he had come to do. His twelve and a half years here profoundly changed his life and the lives of many others.

O N A MILD Tuesday afternoon in August of 1993 I had an appointment with Shunryu Suzukis widow of almost twenty-two years, Mitsu Suzuki. Walking up the central steps to the second floor of the San Francisco Zen Centers three-story redbrick building, I passed the founders alcove, dedicated to Shunryu Suzuki. It is dominated by an almost life-size statue of him carved by an old Japanese sculptor out of a blond cypress stump from the Bolinas Lagoon. Hi Roshi, bye Roshi, I muttered, bowing quickly as I went by.

Mitsu Suzuki-sensei was the person on my mind. We had been close, but I hadnt seen her much in recent years. Soon she would move back across the Pacific for good. I was a little nervous. I needed to talk to her, and although there wouldnt be much time, I didnt want to rush. What I sought was her blessing.