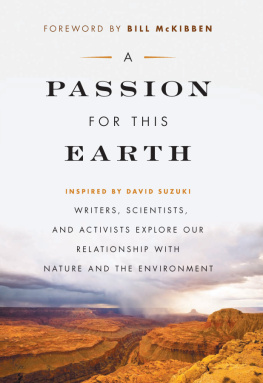

A PASSION FOR THIS EARTH

INSPIRED BY DAVID SUZUKI

WRITERS, SCIENTISTS,

AND ACTIVISTS EXPLORE OUR

RELATIONSHIP WITH

NATURE AND THE ENVIRONMENT

FOREWORD BY BILL MCKIBBEN

EDITED BY MICHELLE BENJAMIN

A

A

PASSION

FOR THIS

EARTH

Essays copyright 2008 by the authors

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a license from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright license, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Greystone Books

An imprint of Douglas & McIntyre Ltd

2323 Quebec Street, Suite 201

Vancouver, British Columbia

Canada V5T 4S7

www.greystonebooks.com

David Suzuki Foundation

2211 West 4th Avenue, Suite 219

Vancouver, British Columbia V6K 4S2

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 978-1-55365-375-2 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-1-926685-05-2 (ebook)

Editing by Nancy Flight

Cover design by Jessica Sullivan

Cover photograph Momatiuk-Eastcott/CORBIS

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit, and the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP) for our publishing activities.

CONTENTS

by Bill McKibben

DAVID HELVARG

RICK BASS

SHARON BUTALA

ADRIAN FORSYTH

RICHARD MABEY

HELEN CALDICOTT

PAUL HAWKEN

SHERILYN MACGREGOR

MICHAEL SHERMER

WAYNE GRADY

ALAN WEISMAN

ROSS GELBSPAN

HEIKE K. LOTZE & BORIS WORM

DOUG MOSS

RONALD WRIGHT

JIM PEACOCK & SHELLY PEERS

CARL SAFINA

THOMAS BERGER

JOHN LUCCHESI

ROBYN WILLIAMS

THERES REALLY NO ONE ON EARTH QUITE LIKE David Suzuki, and this volume illustrates why.

In his early life, Suzuki was perhaps Canadas finest bench scientistJohn Lucchesis recollections set the scene and make his lab sound wonderfully alive. More than a lifetimes work.

But that wasnt enough. Life on a microscale was fascinating to him, but so was life macroversion. Trees and whales and lichen and birdssoon he had translated his passion for the world around him into the planets most popular nature program. Those who think this is an easy task should survey the field: endless British-accented documentaries drying up the natural human love for wild things. Instead, Suzuki turned people on, turned them on to the delights that so many describe in these pages. He became the terrestrial version of Jacques Cousteau, translator of all that was wonderful into the vernacular of a culture that had turned away from the natural. More than a lifetimes work.

But that wasnt enough either. Its always hard to say where the thirst for political action comes from, the thirst for justice. Perhaps it was Suzukis early days in an internment camp during World War II; certainly it was the sight of all that he cared about being quickly blenderized by the onslaught of progress. And so he rose up and fought. Fought eloquently, with his voice and his personal witness. Fought diligently, with his foundation and his reporting. Fought fairly, cleanly, nobly.

Does it matter? Its mattered enormously along Canadas Pacific coast and in dozens of other specific places. Its too early to know if its mattered enough on the great question of the day, climate change, but as several of these essays make clear, his passion and his relentless intelligence have surely helped turn the tide.

The variety of essays in this book is the surest testament to Suzukis life. There are very few other people for whom it would make perfect sense to write about global warming policy, as Ross Gelbspan does, and about media reform and its impact on the Earth, as Doug Moss does, and about the magnificent Carapa tree, as Adrian Forsyth does. Most of us pick one area and dig in.

But the central truth of ecology, the great emergent science of our time, is that everything is connected. And in the cultural ecology, Suzuki is one of those connectors, a crucial hub in the network that Paul Hawken describes as spreading across the Earth. Connecting biology and policy and economics and art, never afraid of the activism that charges those connections, Suzuki has become an organizing principle. The world is not entirely lucky at the momentin fact, it looks as if were entering a period of enormous stress, whose outcome is by no means assured. But were lucky indeed to have a man like David Suzuki and to be able to honor him with our words.

Bill McKibben

FALLING

inLOVEwith

theWILD

The way we see the world shapes the way we treat it. If a mountain is a deity, not a pile of ore; if a river is one of the veins of the land, not potential irrigation water; if a forest is a sacred grove, not timber; if other species are our biological kin, not resources; or if the planet is our mother, not an opportunitythen we will treat each one with greater respect. This is the challenge, to look at the world from a different perspective.

{ DAVID SUZUKI }

David Helvarg

MY SISTER RECENTLY DIED AND THAT GOT ME thinking about our childhood. My best memories of our growing up on New Yorks Long Island Sound involved waterstanding, brackish, and salty.

My friends and I used to play in the swamp behind our school and wade around in the sounds shallows searching the muddy waters with our feet for the primitive armored shapes of horseshoe crabs, which we would lift up by their spiky tails for closer inspection. Early on our boys culture divided between those of us who defended the rights of horseshoe crabs to be played with and skipped across the water and older hoods who liked to imprison them in rock corrals and then smash their shells with heavy stones. After one fight in which by dint of numbers we vanquished a group of hoods, a gray-haired eel fisherman came over to congratulate us, explaining how sometimes you have to fight for the creatures who cant fight for themselves.

Today there are thousands of grown-up kids defending horseshoe crabs, American eels, and other creatures threatened with extinction. Along the Jersey and Delaware shores, where millions of horseshoe crabs have been harvested for eel bait and the loss of their multitudinous eggs threatens migrating shorebirds, marine activists have won new protections for these animals that were ancient when dinosaurs were the coming thing. Others are defending the endangered American eel, whose Homeric journey from the Sargasso Sea along the Gulf Stream to the headwaters of North Americas eastern rivers is now hampered by dams, development, and a global seafood market that includes Asian demand for glass eels or baby elvers, which once sold for as much as ten dollars a pound.

Next page

A

A