ZEN MIND,

BEGINNER'S

MIND

SHUNRYU SUZUKI

First Master of Zen Center,

San Francisco and Carmel Valley

edited by Trudy Dixon with a preface by Huston Smith and an introduction by Richard Baker

PREFACE

Two Suzukis

A half-century ago, in a transplant that has been likened in its historical importance to the Latin translations of Aristotle in the thirteenth century and of Plato in the fifteenth, Daisetz Suzuki brought Zen to the West single-handed. Fifty years later, Shunryu Suzuki did something almost as important. In this his only book, here issued for the first time in paperback, he sounded exactly the follow-up note Americans interested in Zen need to hear.

Whereas Daisetz Suzuki's Zen was dramatic, Shunryu Suzuki's is ordinary. Satori was focal for Daisetz, and it was in large part the fascination of this extraordinary state that made his writings so compelling. In Shunryu Suzuki's book the words satori and kensho, its near-equivalent, never appear.

When, four months before his death, I had the opportunity to ask him why satori didn't figure in his book, his wife leaned toward me and whispered impishly, "It's because he hasn't had it"; whereupon the Roshi batted his fan at her in mock consternation and with finger to his lips hissed, " Shhhh! Don't tell him!" When our laughter had subsided, he said simply, "It's not that satori is unimportant, but it's not the part of Zen that needs to be stressed."

Suzuki- roshi was with us, in America, only twelve years- a single round in the East Asian way of counting years in dozens--but they were enough. Through the work of this small, quiet man there is now a thriving Soto Zen organization on our continent. His life represented the Soto Way so perfectly that the man and the Way were merged. "His non-ego attitude left us no eccentricities to embroider upon. Though he made no waves and left no traces as a personality in the worldly sense, the impress of his footsteps in the invisi ble world of history lead straight on.''* His monuments are the first Soto Zen monastery in the West, the Zen Mountain Center at Tassajara; its city adjunct, the Zen Center in San Francisco; and, for the public at large, this book.

Leaving nothing to chance, he prepared his students for their most difficult moment, when his palpable presence would vanish into the void.

If when I die, the moment I'm dying, if I suffer that is all right, you know; that is suffering Buddha. No confusion in it. Maybe everyone will struggle because of the physical agony or spiritual agony, too. But that is all right, that is not a problem. We should be very grateful to have a limited body like mine, or like yours. If you had a limitless life it would be a real problem for you.

And he secured the transmission. In the Mountain Seat ceremony, November 21, 1971, he installed Richard Baker as his Dharma heir. His cancer had advanced to the point where he could march in the processional only supported by his son. Even so, with each step his staff banged the floor with the steel of the Zen will that informed his gentle exterior. Baker received the mantle with a poem:

This piece of incense

Which I have had for a long long time

I offer with no-hand

To my Master, to my friend, Suzuki Shunryu Daiosho

The founder of these temples.

There is no measure of what you have done.

Walking with you in Buddha's gentle rain Our robes are soaked through,

But on the lotus leaves Not a drop remains.

*From a tribute by Mary Farkas in Zen Notes, the First Zen Institute of America, January, 1972.

Two weeks later the Master was gone, and at his funeral on December 4 Baker- roshi spoke for the throng that had assembled to pay tribute:

There is no easy way to be a teacher or a disciple, although it must be the greatest joy in this life. There is no easy way to come to a land without Buddhism and leave it having brought many disciples, priests, and laymen well along the path and having changed the lives of thousands of persons throughout this country; no easy way to have started and nurtured a monastery, a city community, and practice centers in California and many other places in the United States. But this "no-easy-way," this extraordinary accomplishment, rested easily with him, for he gave us from his own true nature, our true nature. He left us as much as any man can leave, everything essential, the mind and heart of Buddha, the practice of Buddha, the teaching and life of Buddha. He is here in each one of us, if we want him.

HUSTON SMITH

Professor of Philosophy Massachusetts Institute of Technology

For a disciple of Suzuki- roshi, this book will be Suzuki- roshi's mind-not his ordinary mind or personal mind, but his Zen mind, the mind of his teacher Gyokujun So-on- daiosho, the mind of Dogen-zenji, the mind of the entire succession-broken or unbroken, historical and mythical-of teachers, patriarchs, monks, and laymen from Buddha's time until today, and it will be the mind of Buddha himself, the mind of Zen practice. But, for most readers, the book will be an example of how a Zen master talks and teaches. It will be a book of instruction about how to practice Zen, about Zen life, and about the attitudes and understanding that make Zen practice possible. For any reader, the book will be an encouragement to realize his own nature, his own Zen mind.

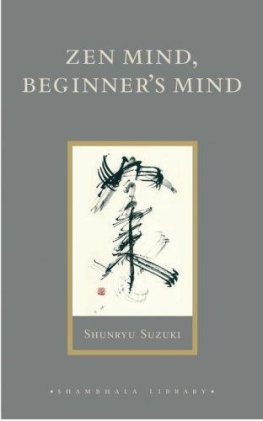

Zen mind is one of those enigmatic phrases used by Zen teachers to make you notice yourself, to go beyond the words and wonder what your own mind and being are. This is the purpose of all Zen teaching-to make you wonder and to answer that wondering with the deepest expression of your own nature. The calligraphy on the front of the binding reads nyorai in Japanese or tathagata in Sanskrit. This is a name for Buddha which means "he who has followed the path, who has returned from suchness, or is suchness, thusness, is-ness, emptiness, the fully completed one." It is the ground principle which makes the appearance of a Buddha possible. It is Zen mind. At the time Suzuki- roshi wrote this calligraphy- using for a brush the frayed end of one of the large swordlike leaves of the yucca plants that grow in the mountains around Zen Mountain Center-he said: "This means that Tathagata is the body of the whole earth."

The practice of Zen mind is beginner's mind. The innocence of the first inquiry-what am I? -is needed throughout Zen practice. The mind of the beginner is empty, free of the habits of the expert, ready to accept, to doubt, and open to all the possibilities. It is the kind of mind which can see things as they are, which step by step and in a flash can realize the original nature of everything. This practice of Zen mind is found throughout the book. Directly or sometimes by inference, every section of the book concerns the question of how to maintain this attitude through your meditation and in your life. This is an ancient way of teaching, using the simplest language and the situations of everyday life. This means the student should teach himself.

Beginner's mind was a favorite expression of Dogen-zenji's. The calligraphy of the frontispiece, also by Suzuki- roshi, reads shoshin, or beginner's mind. The Zen way of calligraphy is to write in the most straightforward, simple way as if you were a beginner, not trying to make something skillful or beautiful, but simply writing with full attention as if you were discovering what you were writing for the first time; then your full nature will be in your writing. This is the way of practice moment after moment.