Lascivious Beast or Shy Vegetarian?

I do not mean to ascribe to him the highest attributes of man, or exalt him above the plane to which his faculties assign him; but there are reasons to justify the belief that he occupies a higher social and mental sphere than other animals, except the chimpanzee.

Richard L. Garner, Gorillas and Chimpanzees (1896)

In 1859 Charles Darwins landmark publication On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life polarized scientific, religious and social debate around the world. Its revolutionary synthesis of knowledge about evolution had a profound and immediate impact upon contemporary thought, as the scientific and theological worlds argued the case for creationism versus evolution. The gorilla was central to this discussion of humanitys place in the biological order in relation to primates.

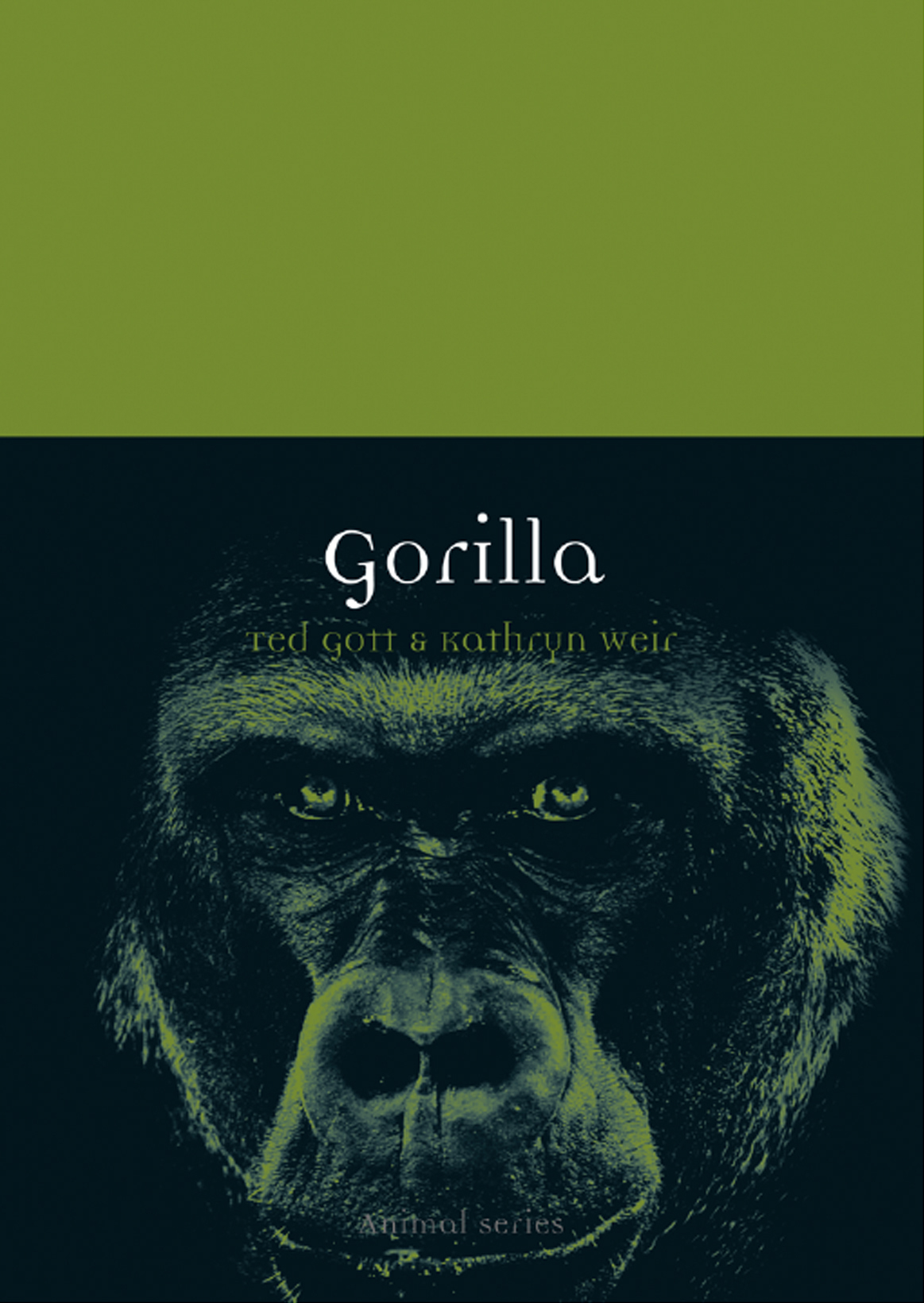

The link between primate studies and the attempt to define the human is the subject of Donna Haraways groundbreaking monograph Primate Visions: Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science (1989). Haraway explores the ways in which, in Europe, America and Japan, gorillas and other apes have been subjected to sustained, culturally specific interrogations of what is means to be almost human, and how stories about primates are simultaneously stories about the relations of nature and culture, animal and human, body and mind, origin and future. The constructed nature of scientific knowledge is particularly clear in relation to gorillas and other apes, positioned as they are as humanitys means of creating its own identity and uniqueness, a phenomenon Haraway calls simian orientalism.

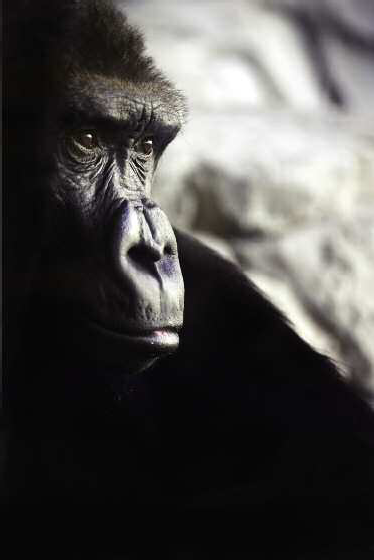

Mountain gorillas, February 2008. |

|

As imaged in art, science, film and popular culture, the gorilla has occupied a prime position in explorations of humanitys animal nature. The social history of the gorilla reflects how quickly scientific study and debate can be drawn into popular culture. In nineteenth-century accounts of observing gorillas in the wild lie the origins of Tarzan, King Kong and many other literary and artistic representations of humanitys relationship with apes. The gorilla has provided a screen upon which to project fears of sexuality and uncontrolled drives, theories of criminality, and narratives of human and primate difference. Little wonder that knowledge of the true behaviour of the gorilla remained extremely limited outside of central Africa until the revelatory field researches of George Schaller and Dian Fossey in the 1950s and 60s.

Gorillas live in primary and mixed forests in regions of central Africa, avoiding human activity and roads, but today they often come in contact with humans in disturbed forests and when taking food from gardens near the forest edge, as well as when they

| Large male silver-back gorilla sitting. |

Western lowland gorilla, Cincinatti Zoo, July 2005. |

|

Nyango, a Cross River gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli), Limbe Wildlife Centre, Limbe, Cameroon, November 2006.

Gorillas, like humans, are classified in the order primates. They are believed to have evolved along paths which diverged from a common anthropoid lineage approximately seven million years ago (rather than being descended one from the other). In the wild gorillas enjoy polygamous sexuality, with each gorilla band or family group usually headed by a male silverback and containing a number of mature females and their offspring, including immature males. New groups may be established when females break away to join a different male silverback gorilla. Highly social, gorillas are relatively stable in these social units, which range in size and configuration; nevertheless, groups consisting solely of males or females respectively are not unknown, and numerous males live a solitary bachelor existence. A silverback in charge of others maintains order within his group, sorting out family disputes and warding off intrusion or attacks from outsiders.