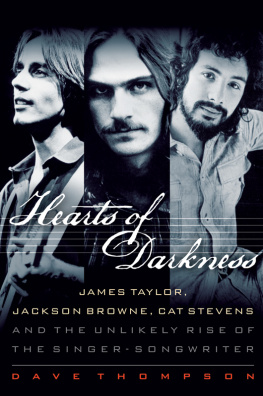

Copyright 2012 by Dave Thompson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, without written permission, except by a newspaper or magazine reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review.

Published in 2012 by Backbeat Books

An Imprint of Hal Leonard Corporation

7777 West Bluemound Road

Milwaukee, WI 53213

Trade Book Division Editorial Offices

33 Plymouth St., Montclair, NJ 07042

Book design by Publishers Design and Production Services, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Thompson, Dave, 1960 Jan. 3

Hearts of darkness: James Taylor, Jackson Browne, Cat Stevens, and the unlikely rise of the singer-songwriter / Dave Thompson.

p. cm.

Includes .

ISBN 978-1-61713-031-1

1. Taylor, James, 1948- 2. Browne, Jackson. 3. Stevens, Cat, 1948- 4. Popular musicHistory and criticism. I. Title.

ML3470.T53 2012

781.64092273dc23

2011047484

www.backbeatbooks.com

Contents

In October 1966, Time magazine published a one-page feature titled The New Troubadours, celebrating the birth of literacy and sensitivity in the world of rock n roll. Five years later, in winter 1971, Who Put the Bomp printed James Taylor Marked for Death, which incorporated journalist Lester Bangss carefully considered plea for literacy and sensitivity to be packed back into the classroomor buried in a pitor thrown off a cliff. Anything, as long as they were finally shut up.

Hate to come on like a Nazi, the bellicose Bangs snarled. But if I hear one more Jesus-walking-the-boys-and-girls-down-a-Carolina-path-while-the-dilemma-of-existence-crashes-like-a-slab-of-hod-on-J.T.s-shoulders song, I will drop everythingand hop the first Greyhound to Carolina for the signal satisfaction of breaking off a bottle of Ripple and twisting it into James Taylors guts until he expires in a spasm of adenoidal poesy.

This book (which actually agrees with Times point of view, but has the Ripple on hand just in case) is the story of what happened in between those two extremes, which means that events later in the performers lives, no matter how much retrospective light they may shed on the events retold here, are not a part of this tale. Jackson Brownes first wife has yet to commit suicide. James Taylor has yet to clean up. Cat Stevens has yet to convert to Islam and endorse the fatwah issued against Salman Rushdie.

Those are tales to be told another time, in another book, because this one is about something else entirely. This is the story of the music that ensured those later events would even be noticed; of the days of struggle, growth, and breakthrough that must take place before fame can be consolidated and celebrity developed; and the story, too, of the lives and lifestyles that contributed to those factors, as they in turn became a part of a wider tapestry, a musical story that for a couple of years at the dawn of the 1970s was set to completely rewire all predictions for the new decade.

Few people, and even fewer music historians, today truly bother to distance the singer-songwriter explosion of 197071 from the events and movements that either preceded or followed it, a state of affairs based largely on the continuity and longevity enjoyed by the best of its progenitorsamong whom James Taylor, Cat Stevens, and Jackson Browne are irrefutably numbered. Yet the first two, Taylor and Stevens, shook away the trappings of the genre that they created at almost the first opportunity they were given; and the third, Browne, never saw himself slipping into their company in the first place.

True, not one of the three would so completely reinvent himself as did Elton John and Neil Young, two other performers who burst through on the same wave of introspective one-man balladeering, and from much the same launching pad, too. Neither, despite their longevity, have their personal legends attained the same peaks as that of Bob Dylan, whose own raison dtre, long before the term was coined, placed him in much the same vein of singer-songwriterdom as they.

Indeed, while those other performers could be said to have continued growing and developing throughout their careers, to the point where a new album from Neil Young or Bob Dylan remains as likely to excite controversy and comment as any older classic, it could be argued that Stevens, Taylor, and Browne have remained relatively static in the years since they unshackled themselves from their earliest burden. It is unlikely that there will ever be a Modern Times or Le Noise from these quarters.

But all have continued, albeit with some disruption and delay, to make music; all have retained and expanded upon their original musical following; and all have, once those adjustments were made, remained true to the notions that they started out with, to write and sing songs that speak straight to the soul of the listener. Baby James is still sweet, Jamaica still says she will, and the peace train is still on a straight track.

This book tells how they reached those points in the first place.

Prologue

Cat Stevens had suffered from writers block before, but early in the New Year of 1973, he acknowledged that, finally, he had reached a stopping point. He was still writing songs; that faucet had never stopped dripping. But they were the same songs hed always been writing, and he was sick of singing songs like that. Hed already made the decision to drop all his older numbers from his live show, but what was the sense in that if the new ones he was penning slipped seamlessly into their place?

He wanted to make a new album; his public demanded it, his record label suggested it, and his own work ethic insisted upon it. But it had to be something new, something different. He had now made six Cat Stevens albums. It was time to make a different one.

Three decades later, he looked back on that dilemma and laughed. I realized it was all going terribly wrong, or a little bit out of control. So I did another whole lets do something different thing. And I went to Jamaica and made Foreigner.

Foreigner is the album that banged the last nail into a musical coffin whose contents had been awaiting burial for a couple of years, but whichwith the same tenacity that always attends the music industrys refusal to acknowledge the passing of its greatest cash cowshad been clinging to life regardless.

The cult of the singer-songwriter was a short-lived one but a powerful one as well. It was born of the folk scenes that devoured early-1960s America and late-1960s Britain, but eschewed the most common methodology of both (Arran sweaters, bushy beards, fingers in the ear, and a nearly nasal twang notwithstanding) in favor of a contemporary beat, a cosmopolitan sheen, and a lyrical thesaurus that was predicated almost exclusively around the word I. Or me.

Ive Got a Thing About Seeing My Grandson Grow Old.

Let Me Ride.

I Thought I Was a Child.

I Want to Live in a Wigwam.

Hey Mister, Thats Me.

Places in My Past.

Ive seen fire and Ive seen rain.

These were not rock n roll songs, although they would be filed in the rock section in the record store. But neither were they a part of any of the other musical genres that the music press of the day tried to file things into. They werent pop, they werent vaudeville, they werent even (although they didnt always admit it) middle-of-the-road. They werent country and they werent folk. They were just there, a handful at first that drifted past your ears, a little laconic, a little bit sad, a touch of melancholy and a slice of psychiatry.

Next page