Pagebreaks of the print version

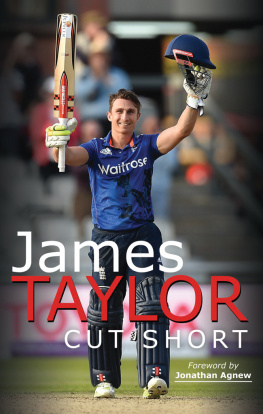

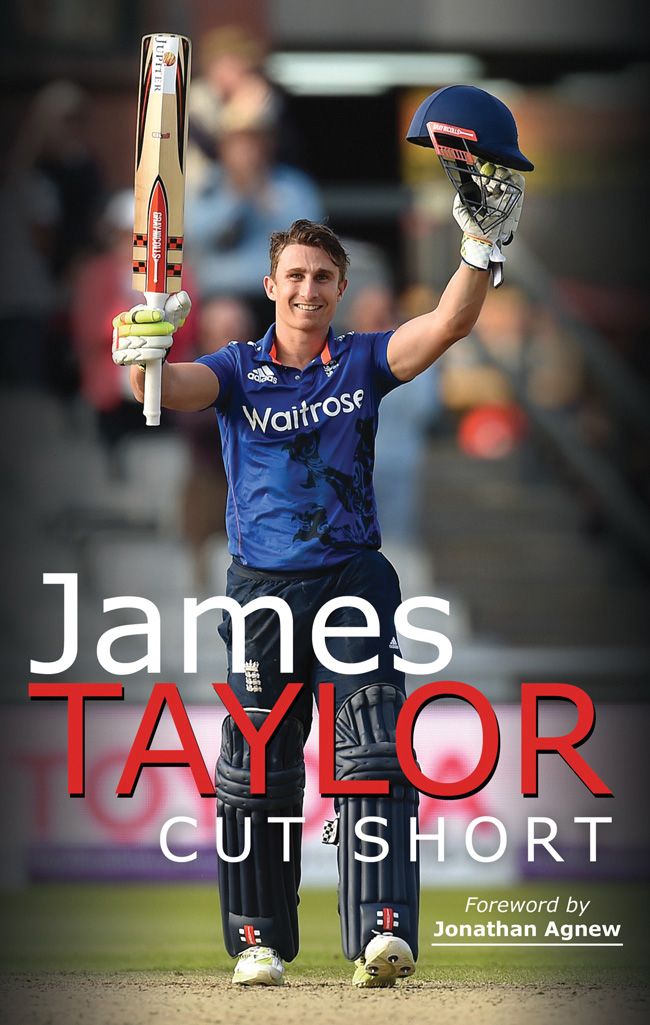

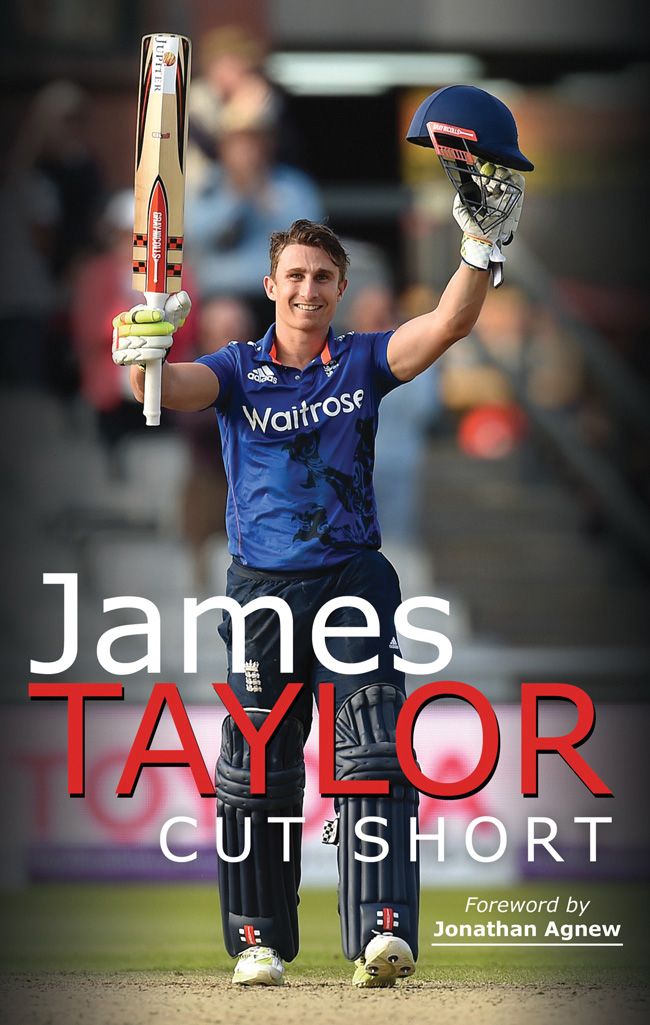

Cut Short

I would like to dedicate this book to my rock and beautiful wife, Jose.

Cut Short

James Taylor

with

John Woodhouse

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by

Pen & Sword White Owl

An imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire - Philadelphia

Copyright James Taylor, 2018

ISBN 9781526732378

eISBN 9781526732385

Mobi ISBN 9781526732392

The right of James Taylor to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Books Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing, Wharncliffe and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Contents

Foreword

T he decision to retire from professional sport is one of the toughest we face. It is a wonderful privilege to make a living from playing a game we love, but nevertheless, choosing the right time to quit is tricky. The danger is we leave it too long, desperately clinging to a lifestyle we do not want to let go, and become merely a shadow of the cricketer we once were. There is no right age to pack up. Graham Gooch, for example, scored twelve Test centuries and 4,500 runs after turning thirty-five, while I took the plunge into a new career aged thirty.

The point is that unless an injury comes along to spoil things, most of us can choose when to go and only very rarely is retirement from professional sport literally a choice between life and death. Yet that is the stark reality that confronted James Taylor in April 2016. He was twenty-six and, apparently, fit as a fiddle.

Geography demanded that I always took an interest in Jamess career. He was brought up in Burrough on the Hill on the Leicestershire border with Rutland, just a few miles from my home. I remember the excitement at Leicestershire County Cricket Club in 2008 when they secured his services, although inevitably his height (5 6) prompted some discussion amongst the members. That Sachin Tendulkar at 5 5 managed to score nearly 16,000 Test runs seemed to pass some by and besides, my experiences of bowling at short batsmen such as the West Indian left-hander Alvin Kallicharran (5 4) inevitably ended unhappily: anything but intimidated by short-pitched fast bowling, they are ruthless cutters and pullers.

Those same members were left grumbling when, in 2012, James mirrored the hard-headed career move by Stuart Broad and transferred to Leicestershires closest rivals, Nottinghamshire. In terms of ambition it was a no-brainer because Leicestershire had long vanished from the England selectors radar and that is the fault of the system, not the players. Not only was James suggesting that he had an international future by scoring centuries for the England Lions, but he was also proving an effective leader. Indeed, before he was forced out of the game, I had seriously earmarked him as a prospective captain of England.

Ironically, I missed the first two days of Jamess Test debut against South Africa at Headingley because I was commentating on archery in the London Olympics. James showed great character in putting on 147 crucial first innings runs with Kevin Pietersen. The match was overshadowed by the revelation that Pietersen had sent messages about the captain, Andrew Strauss, to the South Africans, and had made disparaging comments about Jamess height. But James put all that to one side, earning respect as a man who clearly responds to a challenge.

As James departed with the squad for the 2015 World Cup in Australia, I bumped into a friend of Carol, his mother, in the local pub. A little fortified, I suspect, I suggested in no uncertain terms to her that at least one of the Taylors, who were unsure if he would be picked, should get themselves out to Melbourne to watch their son playing for England against Australia in the opening match of the tournament. The message was conveyed, and Jamess father Steve frantically booked last-minute tickets and arrived on the morning of the match.

I am so glad he was there, for this was an extraordinary spectacle. In the worlds biggest cricket stadium, packed to the rafters with hostile Australian supporters, one of the worlds smallest batsmen was bravely trying to avoid defeat to the old enemy. The cause was becoming increasingly hopeless, but James was playing a different game to the rest: my word, he batted well that evening. Chasing a massive 343 to win, England slumped to 92/6, but demonstrating his competitiveness, James hit 98 from 90 balls. No one else scored more than 37. A shambolic end resulted in the umpires incorrectly giving Jimmy Anderson run out and thereby denying James a certain century. I was commentating on the radio and was furious, but once again his character had caught the eye; and how proud his father must have felt.

In Cape Town the following year, Steve and Carols timing was impeccable once again. This time they arrived in South Africa hours after James was out first ball in the New Year Test. This was a crucial series as James was given the chance to cement his place in the England Test team once more. Runs in Durban set him up, but just as crucial were some astonishing catches at short leg. Well, I say short leg. In fact, this was a careful placement of his own creation; deeper than usual to catch the ball from the full face of the bat. Typically, James had grasped the opportunity that fielding in the most unpopular position of all had presented and he set out to make himself the best in the business. He returned home firmly established as Englands number five. Three months later, a potentially fatal heart condition forced him to retire.

The news shocked us all. I remember being so stunned that I could barely believe it. How, I wondered, would the fittest of young men who loved gym work, respond to being restricted to little more than pottering round the golf course?

Needless to say, James has confronted the situation head-on. We are thoroughly enjoying his company and his insight on the modern game on Test Match Special. I knew he would be good when, early on, he criticised a poor performance by his former Nottinghamshire teammates on air never easily done. And I am assured that his golf has quickly become fiercely competitive. In fact, to borrow one of his words, he has become quite the badger.