The Colony

JOHN TAYMAN

A LISA DREW BOOK

SCRIBNER

New York London Toronto Sydney

For my family

A LISA DREW BOOK/SCRIBNER

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2006 by John Tayman

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

SCRIBNER and design are trademarks of Macmillan Library Reference USA, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, the publisher of this work.

A LISA DREW BOOK is a trademark of Simon & Schuster Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales: 1-800-456-6798 or business@simonandschuster.com

DESIGNED BY ERICH HOBBING

Text set in Minion

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tayman, John.

The Colony/John Tayman.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. LeprosyHawaiiMolokaiHistory. I. Title.

RA644.L3T39 2005

614.5460996924dc22

2005047767

ISBN-13: 978-0-7432-3300-2

ISBN-10: 0-7432-3300-X

eISBN-13: 978-1-43914-142-7

Contents

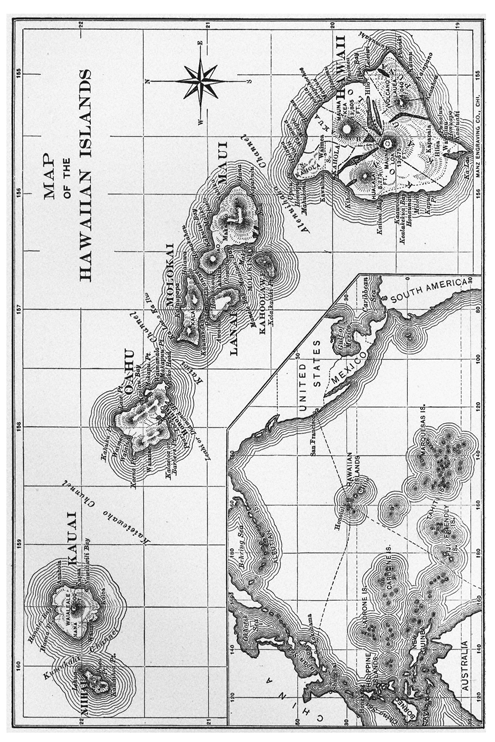

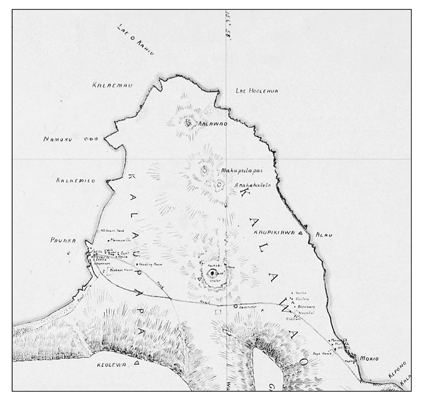

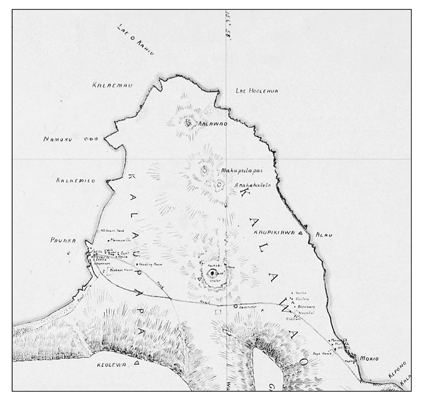

An 1895 map of the Kalaupapa peninsula.

Preface

At 8 A.M. on Friday, September 26, 1947, a thirty-nine-year-old Honolulu physician named Edwin Chung-Hoon began to examine his second patient of the day. Chung-Hoon was a graduate of the Washington University School of Medicine, and his specialty was dermatology. He was currently on active duty with the U.S. Army Medical Corps and had been since the first days following the attack on Pearl Harbor, almost six years earlier. Much of the doctors time, however, was spent on behalf of the Territory of Hawaii s board of health.

His patient that morning was a sweet-natured twelve-year-old boy. Chung-Hoon noted a slight inflammation of the childs right cheek, and minor thickening of the flesh at several sites on his face and body. Laying his hand on the boys cool cheek, Chung-Hoon traced his fingertips upward from the jaw, gently searching for the area where the highway of facial nerves flowed together and then branched away. After a moment the doctor took hold of the childs right ear, then his left, and with the corner of a fresh razor blade cut a small incision a few millimeters in length at their base. The boy was silent during the first slice; when the doctor nicked the second lobe, his patient let out a wounded gasp. Chung-Hoon then made a bacteriological examination of the material he had excised. The process took about an hour. He entered the waiting room and told the boys father the results: leprosy. One week later, the twelve-year-old was exiled.

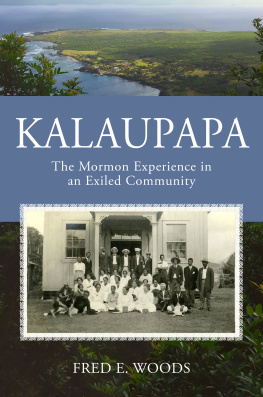

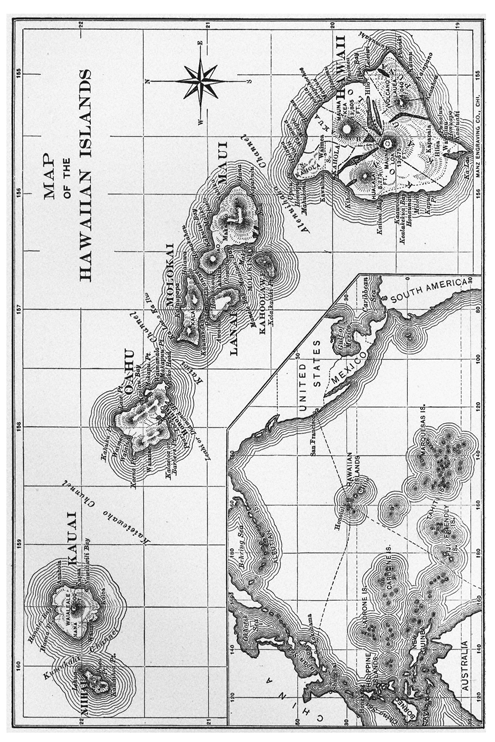

For 103 years, beginning in 1866, the Hawaiian and then American governments forcibly removed more than eight thousand people to a remote and inaccessible peninsula on the Hawaiian island of Molokai, and into one of the largest leprosy colonies in the world. The governments did so in the earnest belief that leprosy was rampantly contagious, that isolation was the only effective means of controlling the disease, and that every person it banished actually suffered from leprosy and was thus a hopeless case. On all three counts, they were wrong.

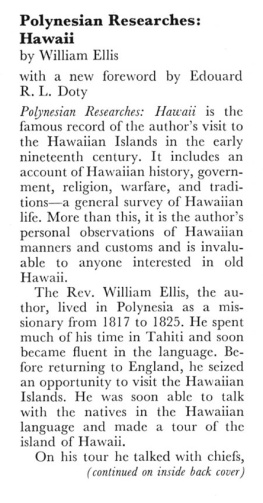

With the establishment of the colony on Molokai, officials initiated what would prove to be the longest and deadliest instance of medical segregation in American history, and perhaps the most misguided. In 1865, acting on the counsel of his American and European advisers, Lot Kamehameha, the Hawaiian king, signed into law An Act to Prevent the Spread of Leprosy, which criminalized the disease. In the first year, 142 men, women, and children were captured. The law in various forms remained in effect through the annexation of Hawaii by America in 1898, the adoption of Hawaii as the fiftieth American state in 1959, and until mid-1969, when it was finally repealed. Under the law, persons suspected of having the disease were chased down, arrested, subjected to a cursory exam, and exiled. Armed guards forced them into the cattle stalls of interisland ships and sailed them fifty-eight nautical miles east of Honolulu, to the brutal northern coast of Molokai. There they were dumped on an inhospitable shelf of land of the approximate size and shape of lower Manhattan, which jutted into the Pacific from the base of the tallest sea cliffs in the world. It was, as Robert Louis Stevenson would write, a prison fortified by nature. Three sides of the peninsula were ringed by jagged lava rock, making landings impossible, and the fourth rose as a two-thousand-foot wall so sheer that wild goats tumbled from its face. In the early days of the colony, the government provided virtually no medical care, a bare subsistence of food, and only crude shelter. The patients were judged to be civilly dead, their spouses granted summary divorces, and their wills executed as if they were already in the grave. Soon thousands were in exile, and life within this lawless penitentiary came to resemble that aboard a crowded raft in the aftermath of a shipwreck, with epic battles erupting over food, water, blankets, and women. As news of the abject misery spread, others with the disease hid in terror from the governments bounty hunters, or violently resisted exile, murdering doctors, sheriffs, and soldiers who conspired to send them away. Some already banished tried to escape, only to fall from the cliff or get swept out to sea. The pit of hell, Jack London wrote, as he undertook a tour of the colony, the most cursed place on earth. The mortality rate for patients in the first five years of exile was a staggering 46 percent.

Leprosy is not a fatal disease. Neither is it highly infectious. It is a chronic illness caused by a bacterium, and communicable only to persons with a genetic susceptibility, less than 5 percent of the population. Transmission takes place much as it does with tuberculosis, through airborne particles expelled by someone with leprosy in an active state. Among untreated patients, only a minority have the disease in its active state; the majority are not contagious. For cases that are active, a multidrug therapy has been developed that quickly renders their leprosy noncommunicable, after which they pose no risk of infection and are, in essence, cured. Every city in America has such cases; in the New York metropolitan area, for instance, more than a thousand people have or have had the disease. There are currently eleven federally funded outpatient clinics in the United States treating approximately seven thousand patients, although health officials believe many sufferers go untreated because of the powerful stigma attached to the disease. Though modern medicine has stripped the illness of its horrors, on a social level leprosy remains among the most feared of all diseases, since untreated leprosy can result in deformity, its precise mode of transmission was until recently unknown, and a cure remained undiscovered for thousands of years. The greatest factor in the stigmatization, however, was the historical intertwining of leprosy with religious notions of divine punishment, which gave rise to the corrosive idea that victims of the disease were sinful, shameful, and unclean. The preferred method of dealing with such people was obvious: banishment.