T his book would not have been possible without the Office of Hawaiian Affairs online archive of Hawaiian-language newspapers and the translations of the Hawaiian-language newspaper articles by Isona Ellinwood and Keao NeSmith.

Special thanks for their support to John Barker, Wendy Bolton, Ruben Boon, Drew Bryan, Stuart Ching, Jason Clark, Koji Clark, Sachi Clark, Brian Daniel, Barbara Dunn, Fern Duvall, George Engebretson, Ann Fagerroos, Kuupua Girod, Sandy Hall, Jennifer Higa, Shoko Hisayama, Takao Hojo, Masako Ikeda, Mie Inage, Robert Kekaianiani Irwin, Luana Kaaihue, Ann Marie Kirk, Shugen Komagata, Luella Kurkjian, Sister Alicia Damien Lau, Jeremy Lemarie, Nadine Little, Jill Matsui, Kaohulani McGuire, Valerie Monson, Alfred Morris, Nancy Morris, Yusuke Motohashi, Sidney Nakahara, Lolena Nicholas, Pua Niau-Puhipau, Naoko Nishiura, Puakea Nogelmeier, Yvonne Ono, Raul Ortega, Tom Penna, Mikiala Pescaia, Barbara Ritchie, Carol Rosa, Kaui Sai-Dudoit, Naoe Sakai, Melissa Shimonishi, Chris Swenson, Julie Ushio, Grace Wen, Fred Woods, Elmer Wilson, and Barbara Wong. x

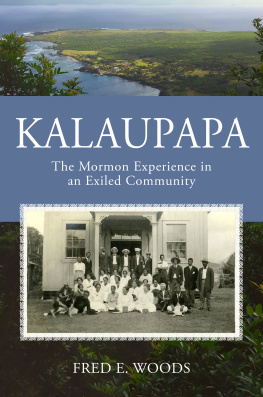

K alaupapa N ational H istorical P ark was established by Congress on December 22, 1980, to preserve the history of the Kalaupapa Leprosy Settlement and to honor the memory of the estimated eight thousand people who were sent there between 1866 and 1959. The story of the settlement, including the subsequent roles of Father Damien (Saint Damien since 2009) and Mother Marianne (Saint Marianne since 2012) has been told many times by many people. The most comprehensive history is Kalaupapa: A Collective Memory by Anwei Skinsnes Law, which was published by the University of Hawaii Press in 2012. The culmination of forty years of research on the history of leprosy in Hawaii, Laws magnum opus is a wealth of information, complete with archival documents, photographs, oral history interviews, and letters from the patients translated from Hawaiian.

Kalaupapa Place Names: Waikolu to Nihoa is also a history of the leprosy settlement, but it differs from the works of other authors by telling Kalaupapas story almost exclusively from more than three hundred Hawaiian-language newspaper articles. From 1834 to 1948, approximately 125,000 pages of Hawaiian-language newspapers were printed in more than a hundred different papers. These newspapers are now an invaluable cultural and historical repository that document the history of the islands as Hawaii moved from a kingdom to a constitutional monarchy to a republic and to a territory of the United States. When I discovered this amazing resource in 2005, I used it to research and write a book on traditional surfing, Hawaiian Surfing: Traditions from the Past (2011), and then again to research Oahus North Shore, which resulted in North Shore Place Names: Kahuku to Kaena (2014). The Hawaiian-language newspaper archive is online and searchable in the Office of Hawaiian Affairs Papakilo Database.

Like its two predecessors, Kalaupapa Place Names: Waikolu to Nihoa is a collection of original historical newspaper articles, most of which have not been translated previously. The translators for this book were Isona Ellinwood, a graduate of the University of Hawaii at Mnoa with a masters degree in Hawaiian, and Keao NeSmith, an applied linguist and researcher who is fluent in Hawaiian. Keao also did the translations for Hawaiian Surfing and North Shore Place Names. In addition to Isona and Keao, Mikiala Pescaia translated several kanikau, and Puakea Nogelmeier assisted as a Hawaiian-language consultant. Articles in Japanese about Dr. Masanao Goto, which were from the National Hansens Disease Museum in Tokyo, Japan, were translated by Shoko Hisayama. xii

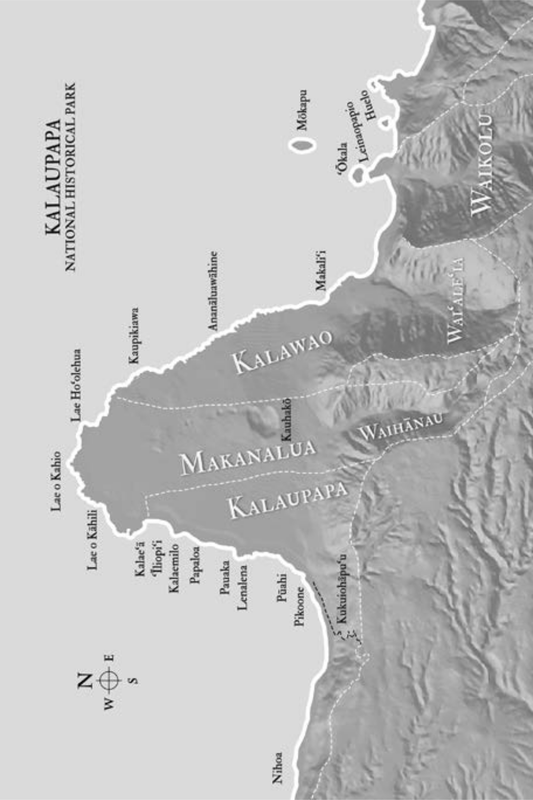

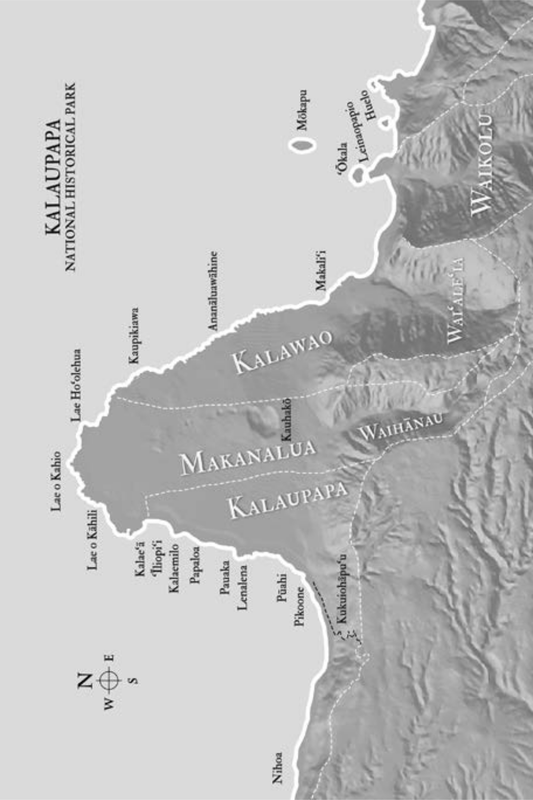

xiii Kalaupapa National Historical Park, the site of Hawaiis historic leprosy settlement, is located on the Koolau, or windward, side of the island of Molokai, one of the four islands in Maui County. Most of the islands seven thousand residents live on the Kona, or leeward, side of the island, while the Koolau side is uninhabited except for the patients and park staff who live in Kalaupapa National Historical Park. As of January 6, 2016, the 150th anniversary of the first patients taken to Kalaupapa, only fifteen patients remained, living either in the park or at Hale Mhalu in Honolulu.

The geographical focal point of the park is a long, wide peninsula that extends into the ocean from the base of the Koolau sea cliffs. Although the Hawaiian language has a term for peninsula, anemoku, Hawaiians did not use it for this wide point of land and instead called it aina plahalaha, or the flat land; kahi plahalaha, or the flat place; kahua plahalaha, or the flat grounds; and kula plahalaha, or the flat plain. While the peninsula is not completely level, it is flat in comparison to the high sea cliffs that stand behind it. In 1921, one writer called the peninsula ka ihu o ka moku, or the bow of the ship, a poetic reference to the fact that it points due north from the island of Molokai, which lies on an east-west axis.

Hawaiians divided the peninsula into three land divisions, which from east to west are Kalawao, Makanalua, and Kalaupapa. When the Board of Health, or Papa Ola, decided to isolate Hawaiis leprosy patients, they selected Kalawao as the site of the first community on the peninsula. This is where the earliest homes and churches were built and where Father Damien lived and died. The settlement also included three coastal valleys: Waikolu to the east of the peninsula and Waialeia and Waihnau, which are directly inland, and the shoreline and sea cliffs west of the peninsula to a small plateau called Nihoa. In 1894, the boundaries of the settlement were defined in a public notice published by the Board of Health in Hawaiian and English that was intended to evict the few remaining residents who were nonpatients.

Keena O Ka Papa Ola.

Hoolaha No Na Kamaaina

Ke hoike ia aku nei i na poe apau e noho ana ma ke Kahua Mai Lepera ma Molokai, no lakou na Kuleana Aina i lawe ia e ke Aupuni no ka hooholo pono ana i na mea i kauoha ia ma ke Kanawai hookaawale no ke kinai ana i ka mai lepera, penei:

Oiai ua hooko ia na mea a pau i koi ia na ke Aupuni e hana no ka uku ana aku i ka poe nona na kuleana ma ke Kahua Mai Lepera, nolaila, ke hoike ia aku nei mai a mahope aku o ka la 15 o Mei, 1894, ua lilo loa no ke Aupuni ia mau waiwai, a o na wahi apau ma ka Anemoku, na alanui, e komo ana iloko a puka xiv iwahomai ia mau wahi aku mai ka Leina o Papio, Waikolu a ke awa o Kalaupapa, a hiki loa aku i, a komo pu mai me, Nihoa, me na ala liilii a alanui apau e pii ai iluna o ka pali a hiki i Kalae, e lilo a e hookaawale ia i Kahua Mai Lepera ma ka Mokupuni o Molokai.