If theres a page in any book that readers are likely to skip, its probably this one. Skip this, however, and you might as well go straight to the end of the book, for the 400 pages in between could not have been written without the help of the following people.

Thanks, first, to my friend David Williams, a superb writer and journalist who gave me the inspiration for this book as long ago as 2010.

Thanks to my agent, Mark Stanton of Jenny Brown Associates, for showing faith in me at the outset, and for his wise advice and encouragement along the way.

At Faber, Id like to thank my editor Lee Brackstone, a genuine football fan, for his vision and passion; Ian Bahrami, my copy-editor, for his exceptionally keen eye and instinctive feel for the book; Anne Owen, my managing editor; and Rachel Alexander and Sophie Portas in publicity, for giving this a nudge in all the right places.

Huge thanks to everyone who agreed to an interview: every quote in this book was given to me directly, unless stated otherwise and every contributor gave his or her time willingly and freely. Hopefully, through your voices, Ive managed to capture something of the spirit of the real football family.

Special thanks must go to Professor Phil Scraton, for his expertise on Hillsborough and its aftermath, and for his invaluable contribution to the campaign for truth and justice; Andy Burnham, Peter Snape, Chris Bryant and Steve Rotheram, for their generosity and candour; Stuart Dykes and Jens Wagner, for their invaluable assistance in Gelsenkirchen and Hamburg; the directors of Schalke 04, who welcomed me into their club with such warmth and honesty; Rogan Taylor and Dave Boyle, for their insight and sheer quotability; the staff at the Tottenham Hotspur Foundation; Chris Platts, lecturer in sport development at Sheffield Hallam University, for his assistance with the chapter on childrens play and their relationship to football; and to Supporters Direct and the Football Supporters Federation and in particular Antonia Hagemann and Michael Brunskill.

Most of the following people are not quoted in the book, but their help was vital. Many thanks to

Jerry Andrews, Philip Bernie, Mike Bracken, Peter Carney, Ian Colledge, David Conn, Alex Eckhout at the Premier League, Tony Edwards, Simon Elliott, Nick Garnett, Owen Gibson, Dan Gordon, Ken Green at the University of Chester, David Hall, Roy Hattersley, Chris Horrie, the late Katy Jones, Damian Kavanagh, Ursula Kenny, Robert Knight at the British Psychological Society, Simon Kuper, Peter Marshall, Nicola McMillan, Steve Melly, Kevin Miles, Judith Moritz, Sean OBrien, Anna Pallai, Dr Martyn Pickersgill at Edinburgh University, Keith, Jan and Bryan Pilgrim, Martin Polley at Southampton University, Ian Preece, Peter Rankin, James Robinson, Jancis Robinson, Erik Samuelson at AFC Wimbledon, Gavin Sandercock at Essex University, Scouse Not English, Mike Shallcross, Jim Sharman, Ben Shave, John Sherar, Christian Spooner at GMG Radio, Mark Stuart at Nottingham University, Alan Sutherill, Toby Syfret and Enders Analysis, Matthew Tetlow at HESA, Tony Trueman at the British Sociological Association, Rhys Williams, and Trevor Williams so sadly missed.

Huge thanks to my family for a priceless head start in life a happy, normal childhood.

Thanks to Anne Williams, for her strength and dignity in the face of decades of cynicism, and to those fellow Reds who shared the most painful of memories in the first chapter of this book. We walk on

Most of all, thanks to Deb for your unfailing faith, and humour, and love, and for being the best thing that ever happened.

It is not unusual for books to be acquired by publishers on the promise and outline of a proposal. Faber did that back in 2011, contracting Adrian Tempany to write the book you are now holding. Adrian delivered a draft of a previous version of this book in the summer of 2013 and we were set to publish in March 2014, 25 years after the Hillsborough disaster, at which he was present.

A month or so before publication, with the book to some degree already in bookshops, the hands of reviewers and early champions, we were advised to withdraw it and postpone publication or risk being accused of contempt of court, as the second inquest opened. In the first few months of 2016, Adrian made substantial changes to the body text of the original (unpublished) edition of And the Sun Shines Now. Specifically, Chapters 9, 10 and 11 were in need of radical updating, as the situation in the Bundesliga had developed in the two-year hiatus between the original publication date and actual publication. The final chapter was written after the verdict on the second hearings was delivered on 26 April 2016.

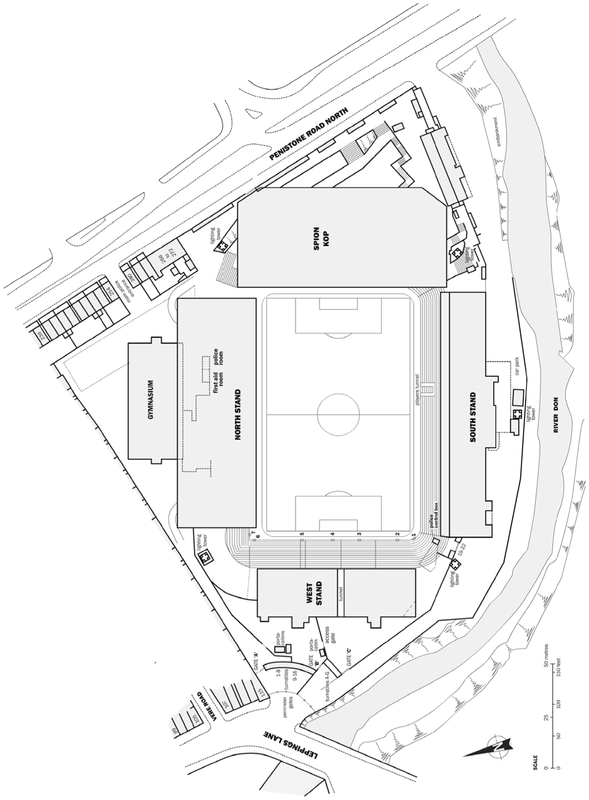

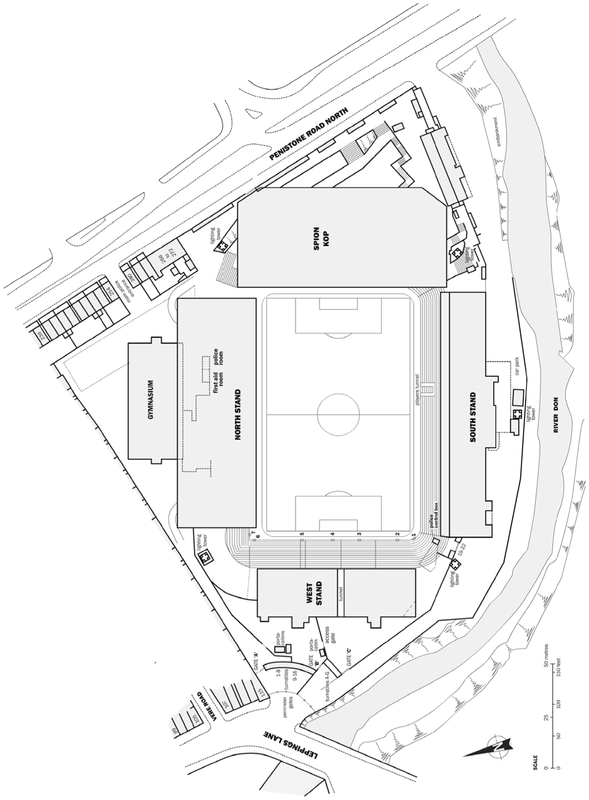

Map of Hillsborough stadium on 15 April 1989 (courtesy of the Hillsborough Inquests www.hillsboroughinquests.independent.gov.uk)

The 1980s began eight months early. On 4 May 1979, Margaret Thatcher arrived at Downing Street, fumbling the spirit of St Francis of Assisi and promising to fix a broken nation with the husbandry of a grocers daughter. In the decade that followed, she defeated and embraced South American dictators, broke Britains most powerful unions, and went toe to toe with the IRA. But even Margaret Thatcher was powerless to write the epitaph for the decade that was unquestionably hers, and which would unravel as it began, eight months early.

On 15 April 1989, 96 people were fatally injured on a football terrace at an FA Cup semi-final in Sheffield. The Hillsborough disaster was broadcast live on the BBC; it left millions of people in shock, and English football in ruins. In the weeks that followed, Britain embarked on an unprecedented period of soul-searching over its national sport.

The bare facts were appalling: 79 of the dead were aged 30 or younger; 37 were teenagers; the youngest was a ten-year-old boy. These, overwhelmingly, were Thatchers children. Many of them died, on that sunny spring day, covered in their own excrement and urine. The coroner at the original inquests recorded that most had died of traumatic or crush asphyxia. Many spent their last moments throwing up, or crying. Some were trampled beneath dozens of pairs of designer trainers, worn by people who were trying desperately to escape, and trying desperately not to stand on their heads. Others made it onto a faded football pitch, only to die on an advertising hoarding.

On the evening of the disaster, as bereaved relatives began their unimaginable journey to Sheffield, journalists at a press conference at South Yorkshire Police headquarters now asked the question on the lips of most people in Britain that Saturday night: Who was responsible for this?

*

In 2009, the country was asking that question again. Twenty years after the biggest disaster in British sport, much of the public were still in the dark about what really happened at Hillsborough. But in March and April 2009, as the 20th anniversary approached, survivors, the bereaved and sympathetic journalists took to the airwaves, the press and the internet to demand the truth. Such was the outcry, the Labour government set up the Hillsborough Independent Panel, a nine-strong committee charged with reviewing all of the remaining documented evidence on the disaster. While the recent inquests in Warrington have delivered the ultimate verdict on the tragedy (and are considered in depth in Chapter 12), this was the moment of truth.