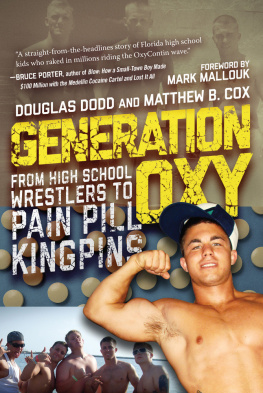

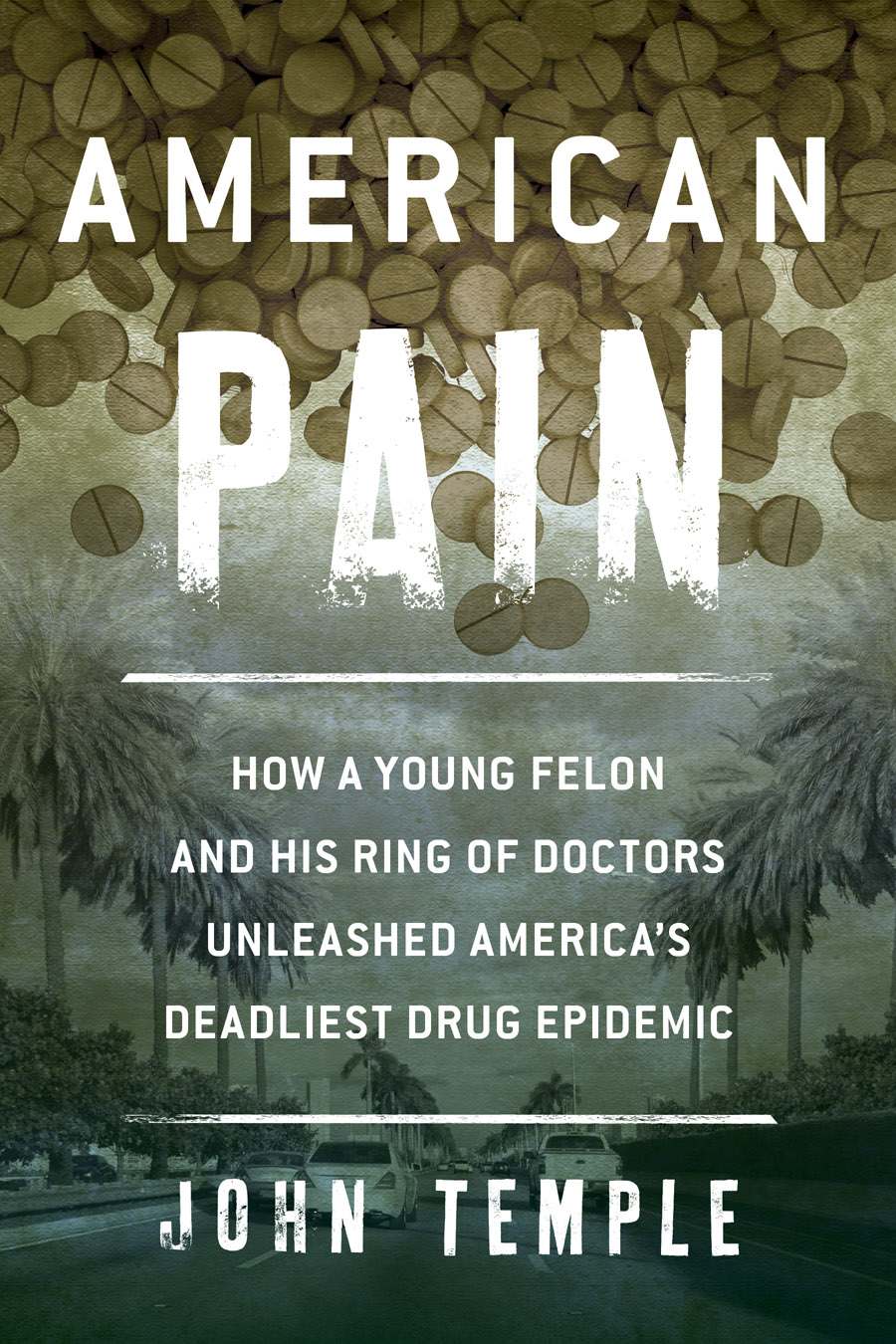

A BOUT THE A UTHOR

John Temple grew up in Chicago, Louisiana, and Pittsburgh. He has worked as a newspaper reporter in Pittsburgh, North Carolina, and Tampa.

Temple is the author of two previous nonfiction books: The Last Lawyer: The Fight to Save Death Row Inmates (2009) and Deadhouse: Life in a Coroners Office (2005). In 2010, The Last Lawyer won the Scribes Book Award from the American Society of Legal Writers. More information about Temples books can be found at www.johntemplebooks.com.

Temple is an associate professor of journalism at the West Virginia University Reed College of Media. He lives in Morgantown, West Virginia, with his wife, Hollee Schwartz Temple, and their two boys.

A MERICAN P AIN

A LSO BY J OHN T EMPLE

The Last Lawyer: The Fight to Save Death Row Inmates Deadhouse: Life in a Coroners Office

An imprint of Rowman & Littlefield

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2015 by John Temple

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

ISBN 978-1-4930-0738-7 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-4930-1959-5 (e-book)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

In passages containing dialogue, quotation marks were used only when the author was reasonably sure that the speakers words were verbatim, such as exchanges taken from court testimony or captured on audio recordings. When a source recounted a conversation from memory, the author did not use quotation marks in that dialogue.

Prologue

Broward County, Florida November 19, 2009

Red caution lights flashed, warning bells chimed. A gold Toyota Camry with Tennessee plates approached the railroad crossing. It was 8:43 a.m., the end of rush hour in Fort Lauderdale.

The crossing gate was halfway down when the Camry lurched forward and slipped under the red-and-white-striped arm. Two hundred yards down the tracks, a train engine came into view, barreling toward the Camry at 60 mph, backed by a 325-ton chain of sky-blue Tri-Rail commuter cars. Plenty of time to get across, but drivers watching from other cars couldnt believe the woman behind the wheel would risk it.

Then the Camry stopped. On the tracks.

For a few agonizing seconds, the car sat motionless as the caution lights alternated, and the warning bells sounded. The Camry driver put the car in reverse, but could back up only a few feet before running into the now-horizontal gate.

Just as the train engine hurtled into the crossing, the driver made an inexplicable decision, gunning the car forward. The engines rail guard slammed the Camry with an unearthly rending reverberation, and the gold sedan became a toy car flung by a child, flipping through the air sixty feet down the track, swiping a small service hut and coming to rest near a cluster of palmetto.

One of the drivers behind the Camry dialed 911 and ran over to help. He knelt by a middle-aged white woman whod been thrown from the mangled car, which was resting on its roof nearby. A few yards away, the mans fiance attended to another bloody woman, younger, and she was praying. Other witnesses were screaming. Blood was everywhere, staining the mans pants. The woman below him gasped for breath.

He said: Everythings OK.

There was nothing he could do but simply be there as she tried to heave oxygen into her broken lungs.

He said: Ambulance is coming. Everythings gonna be OK.

And soon the paramedics did come, and the cops, and the reporters, but they were too late. Both women died beside the train tracks. A man who was in the car was still alive, and they took him to North Bro-ward Medical Center. Crime scene investigators searched the crumpled, upside-down Camry and found an amber prescription bottle and a scattering of blue pills.

And thats when everything made sense, as it would to any cop or paramedic or reporter working in South Florida in 2009. The Tennessee plates. The drivers bad decisions. Her sluggish reactions.

Oxy.

Talking to his best friend and boss over the phone at a quarter after eight the next morning, Derik Nolans growling voice was as full of swagger and humor as usual, and it also contained an edge of wonderment, like, you believe this shit? Something Derik still felt every day working at American Pain. Wonderment at the things he witnessed, the jams that human beings, including himself, would get themselves into while they were trying to get the thing they wanted.

They tried to fucking weave through a railroad crossing and got hit by a fucking train yesterday, Derik said. Two of them are dead. One of them is in critical condition.

Derik was sitting in his office at American Pain, underneath the Spartan warrior swords hed bought and mounted on the wall after seeing the movie . A few minutes earlier, a woman at one of the MRI services he used had called and told him to look at the Sun-Sentinel . Derik had immediately pulled the story up on his computer: two women from Tennessee killed in a train crash, another man badly injured. Deriks contact was all upset because the police had called her after finding an MRI report from her company among the wreckage, along with a bunch of pills. Shed looked up the dead women; theyd been American Pain patients.

After that initial conversation, Derik had called Chris George about the story. Chris had just turned twenty-nine, three years younger than Derik, but he was the boss.

Did it say they were pain clinic people? Chris asked.

No, the story doesnt say anything about pills or American Pain. But it will tomorrow, Derik predicted.

Oh yeah? Chris said.

Itll say tomorrow that there was roxies scattered throughout the car.

It wasnt good news, but, hey, add it to the list of administrative headaches that came with running the biggest oxycodone clinic in the country. Headaches like the upstart pain clinic that was getting ready to open in Jacksonville. Those crooks were trying to steal Deriks patients, calling them up in Kentucky and saying they were a new branch of American Pain. Derik was going to have to drive up there and put the fear of God into them, show them who was top dog.

Or, speaking of problems, how about the story in the Palm Beach Post five days earlier about a different dead patient, a guy whod overdosed after going to a pain clinic that belonged to Chris Georges twin brother, Jeff. And Jeffs dumbass quote to the reporter comparing the dead guy to his car: If I wreck my Lamborghini, am I going to hold the Lamborghini dealership responsible? The quote was funny, and Derik thought it made sense, but it was needlessly inflammatory, perfectly in keeping with Jeffs general attitude that everyone better get out of his way. Jeff, who was right now suing Chris, his own twin brother. Jeff thought Chris owed him a cut of American Pain because it had been Jeffs idea to start a pain clinic. Whereas Chris thought that because Jeff had done almost none of the work actually building or running the place, he wasnt entitled to half the profit.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.