I AM indebted to the late Philip Youngman Carter for the idea of this book, and for his help and encouragement.

Permission to reproduce extracts and illustrations was generously given by the Directors of the Amalgamated Press (now absorbed in the International Publishing Corporation), the Directors of Messrs D. C. Thomson and Co., the Editors and Publishers of TheTatler and Horizon and the late George Orwell.

I am grateful to Mr W. Howard Baker, of the Howard Baker Press, for helping me to bring up to date, for this third edition, the saga of Sexton Blake.

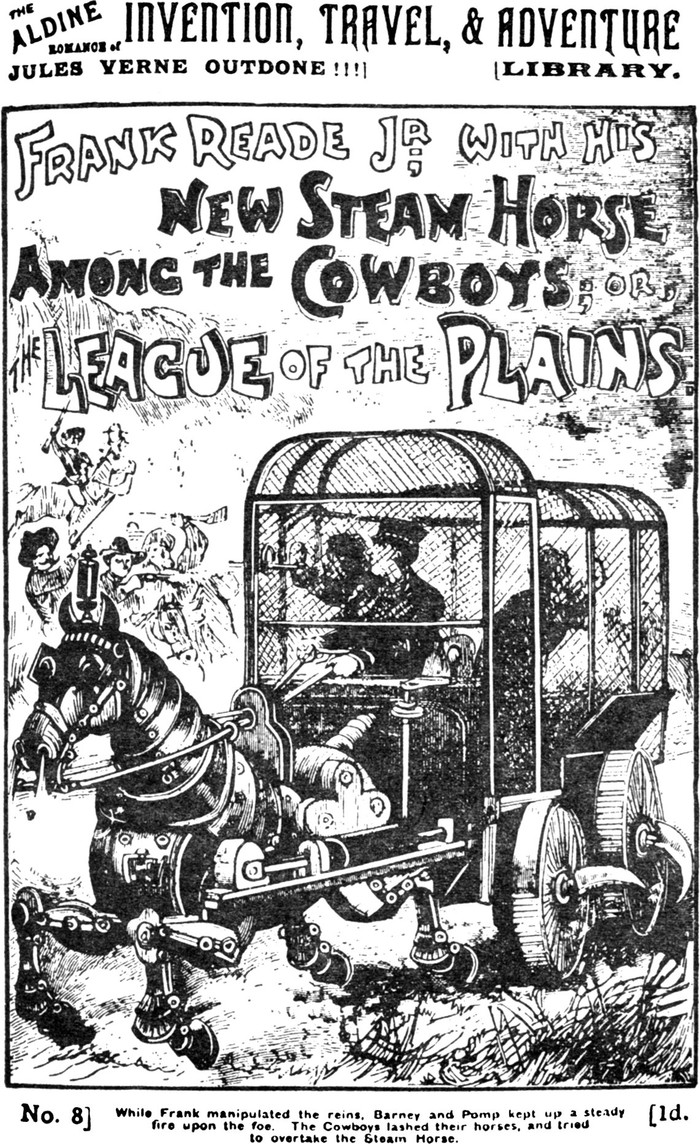

BoysWillBeBoys was first published in 1948, when the juvenile idol of the day was the BBCs Dick Barton. It was revised and extended in 1957, after the Parliamentary battle over horror comics. By that time the picture-strip was well on the way to ousting the printed story. The theory was (and is) that youth reared on television are capable of assimilating print only if it is accompanied and sustained by pictures.

In the space of a generation the cry has changed from Yaroooh! to Aaaaargh! The boys of Greyfriars are not entirely lost to the bookstalls, but they appear in handsome facsimile volumes of the Magnet tailored for the nostalgia trade. Frank Richards, otherwise Charles Hamilton, creator of Billy Bunter and Harry Wharton and Co., died on Christmas Eve, 1961, in his eighty-sixth year. A biography of this Grand Old Man, whose early life remains something of an enigma, is being written by a relative. He may be the first man to have achieved an entry in WhosWho under an alias. His white-haired admirers still meet to discuss and analyse his writings.

The BoysOwnPaper died in 1967. It had long fought the good clean fight, but if its fans ever met for readings from the works of Talbot Baines Reed they kept their sessions secret.

Sexton Blake, when this book was last revised, had just shaken off sixty years asceticism and had introduced provocative young women into his entourage. Older readers dared not think what changes might follow the dissolution of the Baker Street monastery. Their worst apprehensions were unfounded. It was a shock when, in 1963, the old SextonBlakeLibrary came to an end, with Blake apparently retired to a foreign strand; but soon afterwards he escaped into hard covers (see Chapter VIII). He was a tougher and worldlier man than the middle-aged moralizer who fell from a balloon into the English Channel in the Marvel of 1893.

Even more hard-nosed and worldly is Nick Carter, the American investigator who will soon be a centenarian. Like Blake he has moved up market. Instead of having his own weekly he has his paperback series. A recent chronicler attributes to him a face that might have belonged to a Renaissance princeling, a sensual mouth and, like Blake, a quizzical eyebrow. We are invited to admire his sexual prowess.

The name Marvel is now worn by a group of comics, American in origin but English in imprint, whose ultra-fantastic characters are compounded of ice, fire, smoke, rubber, sand and builders rubble. They are touched on in the last chapter.

The Dundee boys papers battle on, as predictably unpredictable as ever. It is rare for a paper to be merged with another and then fight its way free again, as the Wizard did. In a recent issue it carried a picture-strip feature based on R. M. Ballantynes Coral Island, as if to show that nothing is too old-fashioned for the jet age. The beefed-up hearties of this group still fight the world wars over again, not to mention earlier imperial wars. Every now and then a Member of Parliament is shocked to find that these papers carry recruiting advertisements for the armed forces. The Dundee publishers declined wisely, one feels to lend any material or encouragement to a celebration of comics organized in 1970 by the Institute of Contemporary Arts. It was entitled, inevitably , Aaaaargh! The SundayTimesMagazine of 29 July 1973 published two alarming, full-page, grainy, dark blue photographs of the mystery men behind the Wizard and Beano; the cover showed a third mystery man pacing through a graveyard. It is hard to believe that such sombre, even sinister-looking, men have been guilty of providing so much innocent enjoyment.

This edition has been revised and brought up to date where necessary, but the list of births, marriages and deaths among boys papers in recent years is so long that no attempt has been made to log them all.

Literature is a luxury; fiction is a necessity.

G. K. C HESTERTON

I N this book the reader is invited to take a backward plunge into the new mythology the mythology of Sexton Blake and Deadwood Dick, of Jack Sheppard, Jack Harkaway and Billy Bunter; of all the idols of boyhood from Dick Turpin down to Dan Dare.

It should not be necessary to do as Alfred Harmsworth did in 1894 when he launched UnionJack, and assure the reader: Y OU N EED N OT B E A SHAMED T O B E S EEN R EADING T HIS !

Of the adult population of these islands, it is doubtful whether half of one per cent could truthfully claim that they had never dipped in their youth into what undiscriminating parents used to call bloods. The writers hope is that many will welcome the opportunity to look back, if not sentimentally, then critically or even shudderingly, at the he-men, the super-men and the bird-men whose adventures they followed under cover of Hall and Knights Algebra or in the precarious privacy of bed.

It was a pity that this type of reading had to be associated with a feeling of guilt, though it may well be that this went to heighten the readers appreciation. Probably there is no product of the human brain which has been the object of such remorseless and misconceived abuse as the boys thriller. On no theme have magistrates, clergymen and schoolmasters talked more prejudice to the reported inch.

G. K. Chesterton in TheDefendant (1901) brought down a withering fire on the critics who were branding penny dreadfuls as criminal and degraded in outlook. He had grown impatient with the thesis that a boy who could not read stole an apple because he liked the taste of apple, but that a boy who could read stole an apple because his mind was aflame with a story about Dick Turpin. No less muddle-minded, he pointed out, were the critics who charged the authors of penny dreadfuls with romanticizing outlaws, and yet praised the works of Scott, Stevenson and even Wordsworth who had done the same thing in the name of literature. Any reader who wished to revel in corruption, Chesterton pointed out, could do so by buying a full-length novel by a fashionable author. Such literature could not be bought at one penny, for if it were published at that price the police would seize it.

Critics had also urged, said Chesterton, that penny dreadfuls ought to be suppressed because they were ignorant in a literary sense, which was like complaining that a novel was ignorant in the chemical sense, or in the economic sense, He said:

The simple need for some kind of ideal world in which fictitious persons play an unhampered part is infinitely deeper and older than the rules of good art, and much more important .

Robert Louis Stevenson, an addict in youth of penny dreadfuls, has told how little he cared about their literary qualities: Eloquence and thought, character and conversation , were but obstacles to brush aside as we dug blithely after a certain kind of incident, like a pig for truffles.