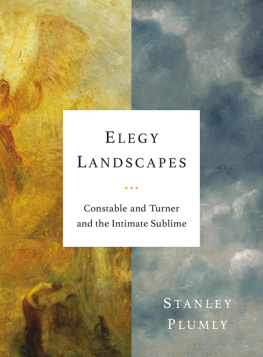

The Grand Canal: Scene A Street in Venice, c. 1837

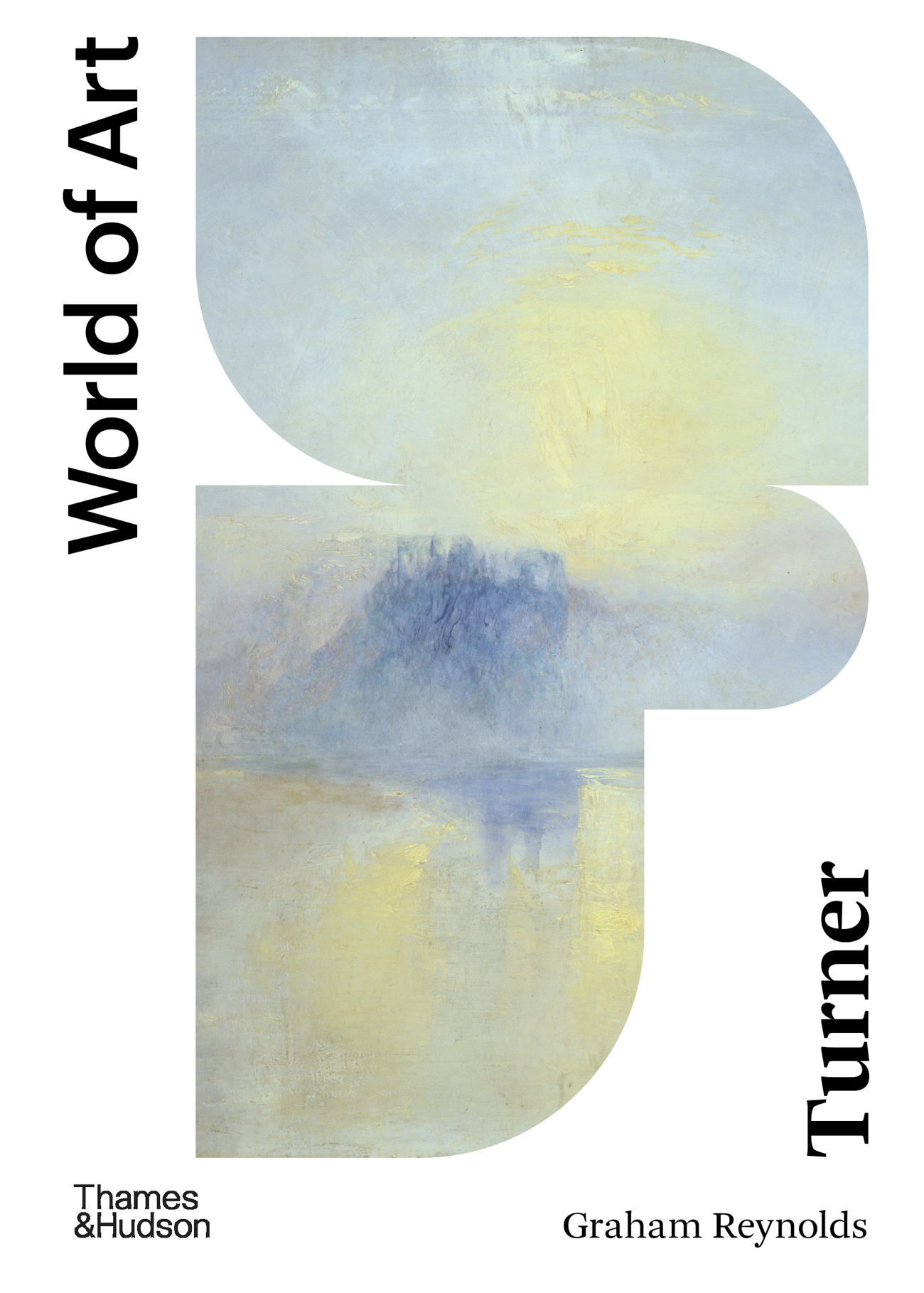

About the Author

Graham Reynolds (19142013) was a former Keeper of the Department of Prints and Drawings and Paintings at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, where he worked from 1937. His other books included English Portrait Miniatures and A Concise History of Watercolours, as well as books on Thomas Bewick and Victorian narrative painters, and the catalogue raisonn of the work of John Constable.

Contents

Melrose Abbey, 1822

Graham Reynolds died, just before his hundredth birthday, in 2013. He had spent most of his career at the Victoria and Albert Museum and stayed active long into retirement. A connoisseur-curator of a species now almost extinct, and an attractive, original character, he had wide interests and was a prolific author. His books included critical biographies and studies of artists, from early miniaturists to Thomas Bewick and Victorian narrative painters (the latter well before they returned to favour), and the catalogue raisonn of the work of John Constable. As a modernist poet he appeared in Michael Horovitzs New Departures alongside Samuel Beckett, William Burroughs and the Beats.

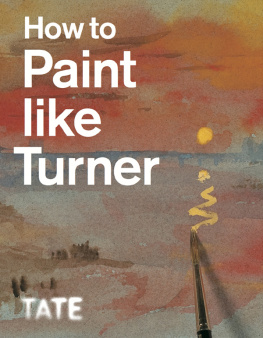

Reynoldss scholarship and expertise no more deterred him from writing for a wide readership than it retreated into narrow specialism. His gift for communicating knowledge and enthusiasm lightly made him an ideal contributor to the World of Art series. Turner first appeared in 1969. In retrospect it seems rather unfair that this became a landmark year for Turner publishing less for this book than for John Gages Colourin Turner: Poetry and Truth, which transformed scholarship through complex and rigorous arguments, extensive use of new or unfamiliar sources and a presentation of Turner as an artist deeply embedded in the culture and intellectual life of his time. There can be no comparison between books of such different length written for different readers. But it is safe to say that many people have enjoyed and learned from both and will continue to do so in years to come.

Writing his book at the same time, Reynolds had no access to Gages penetrating discussion of a wide spectrum of Turners work, although it says something for the breadth of his own approach that he took Constables observation about Turners wonderful range of mind as the title for one of his chapters, just as Gage did for a full-length book on the artist eighteen years later. He could, however, pay tribute to Lawrence Gowings analysis of abstract tendencies in the predominantly later, unfinished sketches chosen for the exhibition Turner: Imagination and Reality at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1966. If Reynolds may occasionally have been too beguiled by Gowings proto-modernist interpretation, he was certainly not alone, and his book steers clear of any overriding thesis to provide an engaging and lively introduction to the artists life and work based on current knowledge. It certainly engaged me as a first-year undergraduate not yet ready for Gage or Gowing (if memory serves, it was the first Turner book I bought). The sources available beforehand scanty compared to todays vast literature show why it had been eagerly awaited. In a brief bibliography indicating his own objectives, Reynolds observed that A. J. Finbergs then standard biography dating from 1939 and reissued, with revisions, in 1961 was rather unimaginatively written and lacking in historical perspective. He had clearly enjoyed Jack Lindsays political/psychological critical biography published in 1966 much more, although anyone who knew him will catch the amused scepticism behind his comment on its many ingenious theories. He recommended Michael Kitsons monograph of 1964 as the most reliable short survey before his own.

Reynolds could not have predicted that his book would be followed within a few years by an explosion of new work on Turner. Spurred on by the Royal Academys bicentenary exhibition of an unprecedented array of Turners work in 19745, the catalogue raisonn of his paintings by Martin Butlin and Evelyn Joll in 1977 (revised 1984), Gages edition of his letters in 1981 and the opening of the Clore Gallery for the Turner Bequest in 1987, research, exhibitions and biographies proliferated on a scale granted to few other artists, let alone British ones. Publications to date were surveyed by Luke Herrmann and (rather more critically) by Michael Kitson in the Oxford Companion to J. M. W. Turner published in 2001 itself a summary of the state of play on many Turnerian fronts written by a host of expert contributors. An update on further reading is essential for this revised edition but, in the spirit of Reynoldss original, it is short and selective. Because the mass of modern scholarship and interpretation can be overwhelming even for specialists, a book like this, far from becoming redundant, is needed more than ever. Herrmanns assessment of it as readable, balanced, and well illustrated still stands.

Wholly unforeseen when Reynolds wrote Turner was the new art history itself now ageing if not already dead, but when it appeared, it divided art historians, perhaps especially those working on landscape painting, into before and after camps. Compared to Michael Rosenthals Constable, published in the World of Art series in 1987, Turner can seem short on social, economic or political context and analysis. However, Reynoldss discussions of the women in Turners life and the artists sympathetic depictions of the poor and their occupations are ahead of their time. Writing in the liberated 1960s, Reynolds was as amused by Finbergs struggles to explain away Turners mistress Sarah Danby as a housekeeper as he was by John Ruskin recoiling from evidence of normal sexual instincts in Turners sketchbooks. At the same time, he understood that for the workaholic, secretive Turner, space between his personal and professional lives was essential. Not known when he was writing, however, was that Sarah was not the young singer and actress who seemed such a tempting candidate for Turners affections but a widow with the same name some years older than her lover. The author cannot be held to account for factual errors or anomalies exposed by subsequent research. In another case of mistaken identity Reynolds accepted as a probability Gages recent suggestion that Turner painted a panorama of the Battle of the Nile shown at the Naumachia in 1799, as well as the (lost) picture he sent to the Royal Academy the same year. Only in 1989 was the Naumachias Mr Turner unmasked as a coach-maker and occasional painter working in Shoreditch.

Inevitably, autograph works have also been subject to revision. Among those included in Reynoldss excellent selection of plates, a large, unfinished harbour scene is now recognized as a view of Brest.[] Most of the watercolours once thought to depict the burning of the old Houses of Parliament in 1834 actually show a fire at the Tower of London in 1841. In this new edition, corrections and clarifications on points such as these have been kept to a minimum and made silently, without comment in the body of the book, so that the text flows seamlessly. That few are needed shows how well it has stood the test of time.

Next page