Author: mile Michel

Layout:

Baseline Co. Ltd

61A-63A Vo Van Tan Street

4 th Floor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City

Vietnam

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Michel, Emile, 1828-1909.

[Mantres du paysage. English]

Landscapes / Emile Michel.

p. cm.

Originally published: Les mantres du paysage. Paris : Hachette, 1906.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Landscape painting, European. 2. Landscapes in art. I. Title.

ND1353.M5313 2011

758.1094--dc23

2011028285

Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Image-Bar www.image-bar.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers, artists, heirs or estates. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-78310-784-1

mile Michel

Landscapes

Contents

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Magpie on the Gallows

(Peasantsdancing under the gallows)

(detail), 1568. Oil on panel, 45.6 x 50.8 cm.

Hessisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt, Germany.

Preface

This book does not claim to be a complete history of landscape painting. The length of such a history would considerably exceed the proportions of this volume, but I have nevertheless endeavoured to give some idea of the order in which the different masters appeared, and of the relative importance of each. Having only to speak here of those who excelled, I have tried to show, in some sort of sequence, whence these artists came, the special merit of each, and his influence on the development of art.

This chronological order was imposed by the subject itself. It is also helpful for the explanation of certain facts. The development of landscape painting did not take place simultaneously, but by turns in the various schools according to the preoccupations of the various regions, and the genius of the great artists distinguished as its exponents.

Our study begins with the Renaissance. As the imitation of nature played but a minor part in antiquity, we need not look for masters in landscape painting there. In Greece, the anthropomorphism of religion prevailed in art as in literature, and among the statuary of the great epoch there is scarcely a fragment of rock or a tree trunk with ivy or vine leaves clinging to it to be found. Although landscape painting occupies a fairly important place in the villas of Rome and the Campagna, it always remains purely decorative, and the pictorial elements to be found in it seem to be merely accidental. Such work, too, was anonymous, and of a secondary order whose facile execution denoted a certain skill: but it does not compare with that close interpretation of nature in which all details are used to enhance the general effect.

We shall not attempt to discuss, in this volume, the way in which landscape painting has been understood and practised in the Far East. In Japanese albums, particularly in those of Hokusa, the varied subjects are rendered with a lifelike and piquant conciseness. Except for degrees of dexterity, these somewhat summary sketches, aced with a clever lightness of touch and drawn without models, are a result of very similar formul. Charming though they are, they lack the individual originality and that rich diversity of feeling that can be appreciated in the European masters. It is to the latter, therefore, that we shall confine our study.

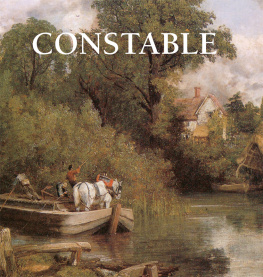

Among these we shall notice many artists who were not exclusively landscapists, and side by side with Claude, J. van Ruisdael, Constable, Corot, Rousseau, and Daubigny, several great masters, such as Van Eyck, Titian, Drer, Poussin, Rubens, Rembrandt and Velzquez, who practised all branches of art, have their place in this volume by virtue of the skill with which they interpreted nature and expressed her beauties. In order to better understand them, I have studied these artists both in their works and in the countries in which they lived, and have endeavoured to point out any special features peculiar to them and to judge the sincerity of their interpretations. It is impossible to thoroughly appreciate Claude and Poussin without having seen Italy, when, different as was their style, it becomes evident that the same scenery inspired them both. It is the same in Holland; at every step one discovers the humble subjects of which Van Goyen, J. van Ruisdael, and Van de Velde have given us such faithful and poetical representations. By living again with them in the countries where their talent was formed, I have more than once come across their favourite haunts, and even the very spot at which they halted.

As regards modern times, it is the uniquely enviable privilege of my age to have come in contact with most of the landscapists who have been the glory of the nineteenth century school. Some of the details which I give concerning them, their careers and their ideas, I have had either from their own lips or from their friends and acquaintances. But to criticise impartially the artists of ones own day, one must not be too near them, and it is for this reason that this volume deals only with those who are no longer with us.

Having made frequent comparisons of very dissimilar works, I have developed the faculty of admiring the most diverse styles and of recognising talent wherever it is to be found.

Chapter 1

The Masters of Landscape Painting in Italy

Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal),

The Porta Portello, Padua (detail), c.1741-1742.

Oil on canvas, 62 x cm .

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa (Portrait of Lisa Gherardini,

wife of Francesco del Giocondo), 1503-1506.

Oil on poplar, 77 x cm . Muse du Louvre, Paris.

Raphael (Raffaello Santi), La Belle Jardinire,

also known as Madonna and Child with Saint John the

Baptist in a Landscape, 1507-1508. Oil on wood,

x cm . Muse du Louvre, Paris.

Landscape painting made its appearance very late in Christian art, and for a long time it played but a minor part. It is not our intention here to treat its humble origins: a few words will suffice to show the clumsiness of its first attempts and the slowness with which it developed. In the mosaics, as in the primitive miniatures, picturesque elements borrowed from nature held a considerable place from an early date, but these purely decorative elements were reproduced in so rudimentary a fashion, that those who depicted them considered it prudent to add the names of the objects which they meant to portray.