Émile Michel - The ultimate book on Rembrandt

Here you can read online Émile Michel - The ultimate book on Rembrandt full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Parkstone International, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

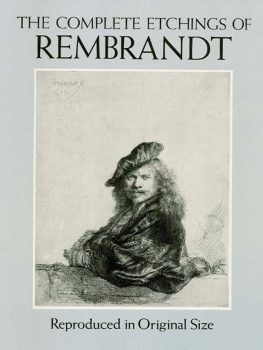

- Book:The ultimate book on Rembrandt

- Author:

- Publisher:Parkstone International

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The ultimate book on Rembrandt: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The ultimate book on Rembrandt" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The ultimate book on Rembrandt — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The ultimate book on Rembrandt" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

mile Michel

The ultimate book

on

Rembrandt

Author:

adapted from mile Michel

Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Image-Bar www.image-bar.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers, artists, heirs or estates. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-64461-782-3

Contents

His Education

Rembrandt was born on 15 July 1606 in Leyden. The date 1606, although very probably the year of his birth, is not absolutely above suspicion. Rembrandt was fifth among the six children of the miller Harmen Gerritsz, born in 1568 or 1569, and married on 8 October 1589, to Neeltge Willemsdochter, the daughter of a Leyden baker, who had migrated from Zuitbroeck. Both were members of the lower middle class, and in comfortable circumstances. Harmen had gained the respect of his fellow-citizens, and in 1605 he was appointed head of a section in the Pelican quarter. He seems to have acquitted himself honourably in this office, for in 1620 he was re-elected. He was a man of education, to judge by the firmness of his handwriting as displayed in his signature. He, and his eldest son after him, signed themselves van Ryn (of the Rhine), and following their example, Rembrandt added this designation to his monogram on many of his youthful works. In final proof of the family prosperity, we may mention their ownership of a burial-place in the Church of St Peter, near the pulpit.

No record of Rembrandts early youth has come down to us, but we may be sure that his religious instruction was the object of his mothers special care, and that she strove to instil into her son the faith and moral principles that formed her own rule of life. Among the many portraits of her painted or etched by Rembrandt, the greater number represent her either with the Bible in her hand, or close beside her. The passages she read, the stories she recounted to him from her favourite book, made a deep and vivid impression on the child, and in later life he sought subjects for his works mainly in the sacred writings. Calligraphy in those days was, with the elements of grammar, looked upon as a very important branch of education. Rembrandt learnt to write his own language fairly correctly, as we learn from the few letters by him still existing. Their orthography is not faultier than that of many of his most distinguished contemporaries. His handwriting is very legible, and has even certain elegance, and the clearness of some of his signatures does credit to his childhood lessons. With a view, however, to his further advancement, Rembrandts parents had enrolled him among the students of Latin literature at the university. The boy proved but an indifferent scholar. He seems to have had little taste for reading, to judge by the small number of books to be found in the inventory of his effects in later life.

Great as was his delight in painting, pleasures even more congenial were found in the countryside surrounding Leyden, and Rembrandt was never at a loss in hours of relaxation. Though of a tender and affectionate disposition, he was always somewhat unsociable, preferring to observe from a distance, and to live apart, after a fashion of his own. That love of the country which increased with years manifested itself early with him. Rembrandts parents, recognising his disinclination for letters and his pronounced aptitude for painting, decided to remove him from the Latin school. Renouncing the career they had themselves marked out for him, they consented to his own choice of a vocation when he was about fifteen years old. His rapid progress in his new course was soon to gratify the ambitions of his family more abundantly than they had ever hoped.

Leyden offered few facilities to the art student at that period. Painting, after a brief spell of splendour and activity, had given place to science and letters. A first attempt to found a Guild of St Luke there in 1610 had proved abortive, though Leydens neighbours, the Hague, Delft, and Haarlem, reckoned many masters of distinction among the members of their respective companies. Rembrandts parents, however, considered him too young to leave them, and decided that his apprenticeship should be passed in his native place. An intimacy of long standing, and perhaps some tie of kinship, determined their choice of master. They fixed upon an artist, Jacob van Swanenburch, now almost forgotten, but greatly esteemed by his contemporaries.

Though Rembrandt could learn little beyond the first principles of his art from such a teacher, he was treated by Swanenburch with a kindness not always met with by such youthful probationers. The conditions of apprenticeship were often very rigorous; the contracts signed by pupils entailed absolute servitude, and exposed them in some hands to treatment which the less long-suffering among them evaded by flight. But Swanenburch belonged by birth to the aristocracy of his native city. During Rembrandt's three years in his trust, his progress was such that all fellow-citizens interested in his future were amazed, and foresaw the glorious career that awaited him.

His noviciate over, Rembrandt had nothing further to learn from Swanenburch, and he was now of an age to quit his fathers house. His parents agreed that he should leave them, and perfect himself in a more important art-centre. They chose Amsterdam, and a master in Pieter Lastman, a very well-known painter at that time. In his studio, methods of instruction much akin to those adopted by Swanenburch were in vogue, though the personal talent modifying them was of a far higher order. Lastman was, in fact, a member of the same band of Italianates, who had gravitated round Elsheimer in Rome.

When Rembrandt entered Lastmans atelier, the master was at the zenith of his fame. His contemporaries lauded him to the skies, proclaiming him the Phoenix and the Apelles of the age. He was further held to be one of the best experts of Italian art, and as this had begun to find favour in Holland, he was often called upon to assess the value of pictures for sales or inventories. His house was a popular one, and his young pupil was doubtless brought into contact with famous artists and other persons of distinction. Such intercourse must have been of great value to him, enlarging his mind and developing his powers of observation.

Rembrandt spent but a short time in Lastmans studio. Lastman, though greatly superior to Swanenburch, had all the vices of the Italianates. His mediocre art was, in fact, a compromise between the Italian and the Dutch ideal. Without attaining the style of the one or the sincerity of the other, and with no marked originality in his methods, he continued those attempts to fuse the unfusible in which his predecessors had exhausted themselves. To Rembrandts single-minded temperament such a system was thoroughly repugnant. His natural instincts and love of truth rebelled against it. Italy was the one theme of his master, that Italy which the pupil knew not, and was never to know. But he saw everywhere around him things teeming with interest for him, things which appealed to his artistic soul in language more intimate and direct than that of his teacher. His own love of nature was less sophisticated; he saw in her beauties at once deeper and less complex. He longed to study her as she was, away from the so-called intermediaries which obscured his vision and falsified the truth of his impressions.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

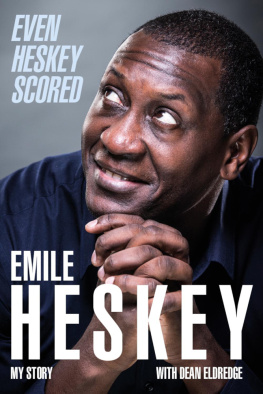

Similar books «The ultimate book on Rembrandt»

Look at similar books to The ultimate book on Rembrandt. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The ultimate book on Rembrandt and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.