My many thanks go to the friends and family who make such a project come to fruition, especially my partner, James Maloney, who has suffered my grumpy moods and obsessive character with his charm and humor. Without the generous support of the Gage Academy of Art and my fine students, where would I be?

To fellow artists, who so generously provided their inspiring paintings within these covers, my lasting gratitude. Special thanks to Tamalin Baumgarten, Isabelle Bosquet-Morra, Chi Chi Stewart, Madeline Crowley, and Heather Comeau Cromwell for their help without question.

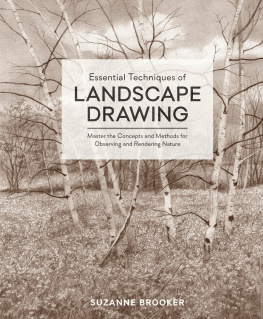

SUZANNE BROOKER received her BFA at the California Institute of the Arts, attended the Whitney Museum Independent Study program in New York City by invitation, and pursued her drawing studies at the School of Visual Arts in New York. She studied life drawing with Gary Faigin at the Gage Academy of Art and completed her MFA in figurative painting at California State University, Long Beach. The author of Portrait Painting Atelier (2010) and creator of the online course Painting Better Portraits with Photographs, Brooker currently teaches drawing and painting at the Gage Academy and conducts workshops from her studio. She resides in Seattle, Washington. Find more of her work at suzannebrooker.com

RECOMMENDED READING

Albala, Mitchell. Landscape Painting: Essential Concepts for Plein Air and Studio Practice . Watson-Guptill, 2009.

Excellent guide to painting principles.

Carlson, John F. Carlsons Guide to Landscape Painting. Dover Publications, 1973.

One of the original treatises on landscape theories and practice.

Cole, Rex Vicat. The Artistic Anatomy of Trees: Their Structure and Treatment in Painting. Dover Publications, 1965.

Intense botanical study of tree growth and pattern.

Curtis, Brian, Drawing from Observation: An Introduction to Perceptual Drawing. McGraw Hill, 2002.

Instruction on measuring, perspective, foreshortening, and other concepts key to drawing.

Hamm, Jack. Drawing Scenery: Landscape and Seascapes. Perigee Books, 1972.

Concepts for landscape drawing with easy-to-follow techniques.

Roberts, Ian. Mastering Composition: Techniques and Principles to Dramatically Improve Your Painting. North Light Books, 2007.

Introduces compositional structures for direct painting.

Sibley, David Allen. The Sibley Guide to Trees. Alfred A. Knopf, 2009.

Reference for identifying trees in North America.

Walker, Claire. Nature Drawing: A Tool for Learning. Prentice Hall, 1980.

Drawing techniques for sketching outdoors, including plants, animals, and birds.

Wilcox, Michael. Perfect Color Choices for the Artist. North Light Books, 2002.

Color palettes combined with historic images demonstrate the effect of pigment choices.

Natural History: The Ultimate Visual Guide to Everything on Earth. DK Publishing, 2010.

Heavily illustrated reference text and resource for images.

RENATO MUCCILLO, ALOUETTE MUD RIVER FLATS, 2011, OIL ON MOUNTED CANVAS, 14 18 INCHES (35.6 45.7 CM).

Through the artists ability to represent light, color, shape, and texture on the painted surface, an ordinary scene can be translated into a beautiful painting.

CHAPTER ONE

GETTING STARTED

In this chapter, Ill cover how to translate your perceptions of a scene into a painting strategy, and how to use the best tools and techniques to carry out your plan. Once youve surveyed this information, itll be much each easier to incorporate the specific painting techniques within the following chapters. After all, a strong start to any painting goes a long way to ensuring its successful finish.

As an intermediate painter, your task is to be self-conscious of your process, mentally noting what works and why. Think of this stage in your painting experience as the time when you watch yourself and the results of your efforts. Remember, the ease and skill that you witness when watching more experienced painters derives from their dedicated application of these same methods. Intuition is based on experience and practice.

MITCHELL ALBALA, COLOR STUDIES, 2012, OIL ON PAPER, 4 4 INCHES (11.4 10.2 CM).

BEGINNING A PAINTING

Painting is a time-consuming activity that demands that artists focus on projects that will help them grow. Before starting a new work, its important to identify your motive: Am I learning a new technique, experimenting with a different palette, building a body of work, or enjoying a free moment to express myself? Your motive becomes your artistic intention in the work and helps determine if youve reached your goal when a painting is finished.

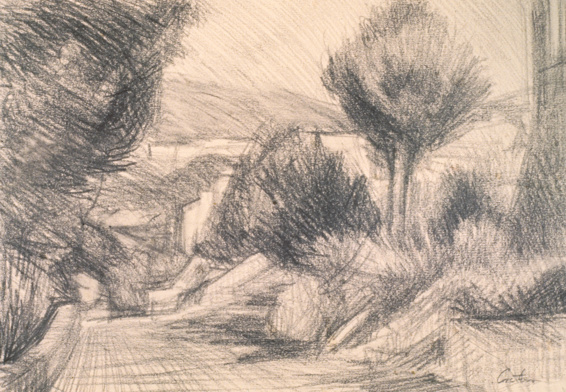

DOMENIC CRETARA, ROAD TO IBIZA, 1977, OIL ON PAPER, 11 15 INCHES (27.9 38.1 CM).

A first allows the artist time to discover the compositional elements that are then later refined in the oil painting (above).

DOMENIC CRETARA, ROAD TO IBIZA (STUDY), 1977, GRAPHITE ON PAPER, 11 14 INCHES (27.9 35.6 CM).

DESCRIBE WHAT YOU SEE

Begin by answering the question What do I see? Is it a tree by the waterside or a rolling meadow leading off to distant hills? Describing what you see can help you start to organize your perceptions. It sounds easy, but it may prove more difficult than you thinkcondensing the rich amount of detail into a bare-bones description. Simplification is the first step toward reducing the chaotic details of a view to overall shapes or a singular focal point.

Here, a viewfinder is helpful in locating the arrangement of landscape elements that will become your picture. A simple viewfinder can be your own hands held in front of your eyes (palms flat facing out in front of you and thumbs touching as they point at each other, rotating one hand so that the open space between your hands resembles a rectangle). Looking through the open space achieves a similar effect to looking through a camera lensit frames a scene in a rectangular shape. In fact, an empty 35 mm slide mount or a plain piece of cardboard with a cutout window can also serve as your viewfinder.