CONTENTS

Contents

Guide

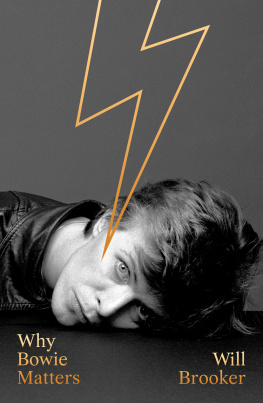

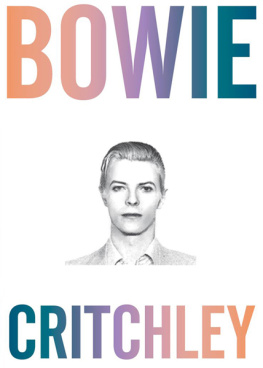

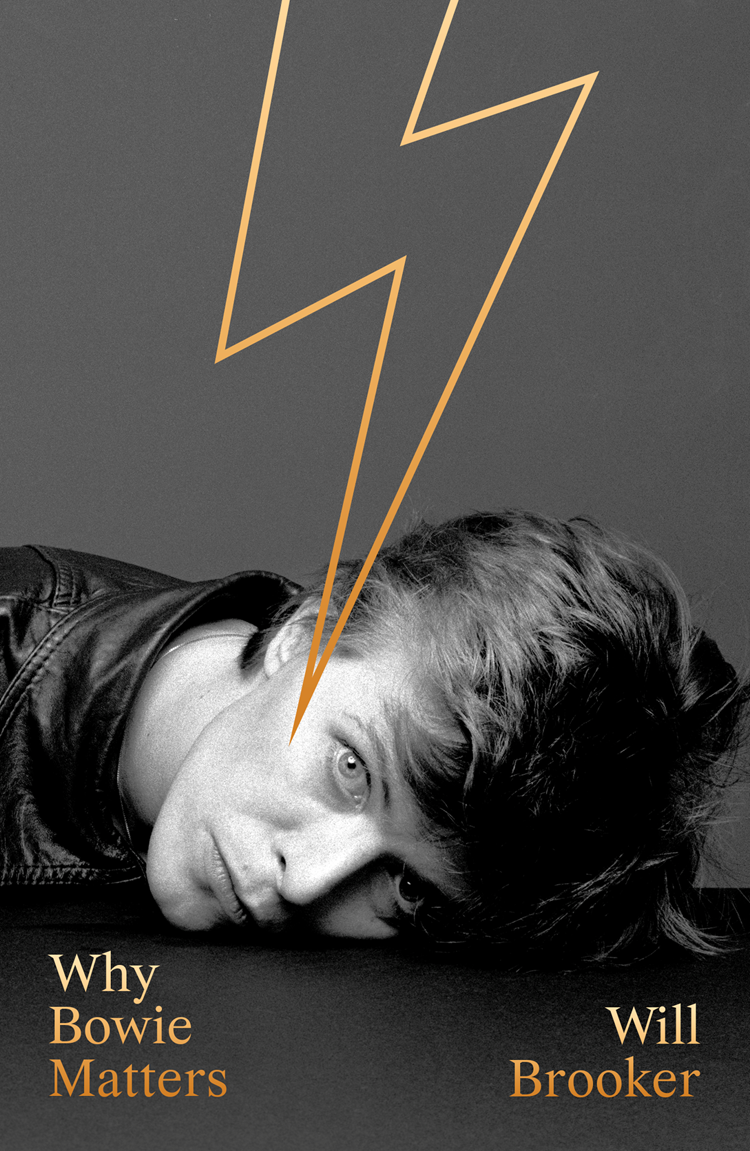

WHY BOWIE MATTERS

Will Brooker

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright Will Brooker 2019

Cover photograph Sukita

Will Brooker asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008313722

Ebook Edition October 2019 ISBN: 9780008313739

Version: 2019-07-22

Things really matter to me.

David Bowie, Afraid

Dad lived ten lives in the years he had! Duncan Joness cheerful tweet on the second anniversary of his fathers death, in January 2018, sums up the popular idea of David Bowie: a man who lived at an accelerated rate and transformed himself with the release of each new LP. In the 1970s alone, he raced from his folk-rock beginnings through Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane, the Thin White Duke, and the blue-eyed soul man of Young Americans, before moving into the introspective Berlin period and finally concluding the decade on the cusp of the mainstream, MTV success that would dominate his 1980s.

Its a familiar story, retold in every biography. This introduction is not that story. This is the story of how my life intersected with David Bowie; how he informed and inspired me from my first encounter with my mums Lets Dance cassette when I was thirteen. It is not about Bowies changes, but about how he changed me from that chance discovery in 1983 to 2015, when I undertook an academic project to live like him for a year, and attempted to compress his entire extraordinary career into twelve months.

Every Bowie fan has a story of the role he played in their life. Mine is unique, just like everyone elses. The purpose of this introduction is not to qualify me as an extraordinary super-fan although my experience was certainly unusual but as a fan like millions of others; as a fan, no doubt, like you. We all have our own sense of Bowie, and that is the point.

David Robert Jones was born on 8 January 1947 and died on 10 January 2016. David Bowie was born, as a stage name, on 16 September 1965. He never really died. David Bowie was a persona created by Jones, but he thrived and survived for four decades not just because David Jones stuck with this name hed previously adopted Luther Jay, Alexis Jay and Tom Jones but because his audiences embraced him: because of his fans.

Bowie became a star, a concept, a cultural icon, because of people like you and me, who took him wholeheartedly into their lives. We invested aspects of ourselves in him, and so a part of him continues in us. This book is a celebration of Bowies importance, and an exploration of his legacy as a cultural icon. But on another level, its also about celebrating our inner Bowie, and letting it change and inspire us. We are all the millions here Bowie gazed at in The Man Who Sold the World in 1970: we are the galaxy of blackstars that he left behind in 2016. We all have our own stories of how he entered our lives and what he meant to us. This is mine.

I was born the year before Duncan Jones, and so while I knew of David Bowie in the 1970s, he stood for something shocking, scandalous and grown-up. He was like the taste of wine or beer: something I assumed Id understand and appreciate later. When the video for Ashes to Ashes played on Top of the Pops in 1980, I found it unpleasant and a bit scary, with its distorted colours, surreal images and flat, repetitive vocals. The droning chorus reminded me of the graffiti I saw on my walk home from school on the wall of a south London housing estate: Sex is good, sex is funky. Sex is best without a dunky. Every week, I wanted the video to end so I could see more of ABBA, Blondie or Adam and the Ants.

But I changed, and Bowie changed. In 1983 I was on holiday with my family, somewhere in the English countryside: seven days of steam train museums, hill walks and horses. I picked up a cassette my mum had brought along: Bowies Lets Dance, his mainstream breakthrough. My mum was thirty-eight at the time, only two years older than Bowie. I was thirteen. I slotted the tape into the red plastic Walkman Id got for Christmas, and didnt take it out all week. My mum never got that cassette back. I still have it now. I asked her recently why shed bought Lets Dance, as I didnt remember her being a Bowie fan in the seventies. She was entranced, she told me: he looked stunningly handsome and desirable, rather than just weird. She even tuned in to Top of the Pops every week, she confessed, to watch the videos. I felt exactly the same way, though we never told each other at the time.

For me in 1983, Bowies music was a soundtrack to imaginary films, the music playing during the love scenes and end credits of movies that were never made. It was a glimpse into a sophisticated, adult world not deliberately shocking, like his singles of the 1970s, but gleaming and stylish, with lyrical cross-references and casually dropped ideas that hinted at the intelligence behind them. March of flowers! he declared on the discordant Ricochet. March of dimes! These are the prisons! These are the crimes! I listened repeatedly, carefully writing down the words; I felt like I was engaging with something challenging and avant-garde. I analysed them as if they were a poem from English class.

It wasnt easy to fit in at my school you needed just the right Farah trousers and Pringle sweaters, the right sports bag, the right haircut and the right couldnt-care-less attitude. I studied too hard and couldnt afford all the proper gear, so I was a boffin, a tramp and probably a poof too. Lads at school said David Bowie was gay. I loved looking at his videos. I recorded them from the Max Headroom TV show, rewinding and freeze-framing them. I liked his sharp suits, his sharp teeth and his pained expression, as if he were struggling with something. In the Lets Dance video, backed against the wall of an Australian bar and surrounded by the glares of hard-drinking men, he didnt look like he fitted in either. Maybe I was gay for feeling that way about David Bowie, but he made me feel it didnt matter.

It turned out I wasnt gay, and it turned out Bowie wasnt either. It didnt matter. We both got married, to women. Nobody told me the groom wasnt meant to have his own theme song playing when he walks down the aisle, so I entered to an instrumental version of Modern Love, wearing a suit I thought Bowie would appreciate. I landed a job as a university lecturer. One winter, towards the end of the last century, I flew to Australia for a conference, via Japan. I took a new Walkman, with only one cassette: a personal Bowie collection Id compiled for the trip. It was my first time alone on the other side of the world. I listened to nothing but Bowie for a week, discovering new songs as I walked by the Brisbane River under the surprising December sun. On the way back I was stuck at Narita Airport, and was taken by coach to a remote hotel overnight. I knew nobody, and didnt speak a word of the language. Id never felt further from home. I listened to one song, on repeat. Now Ashes to Ashes made sense to me, in all its alien strangeness and isolation.