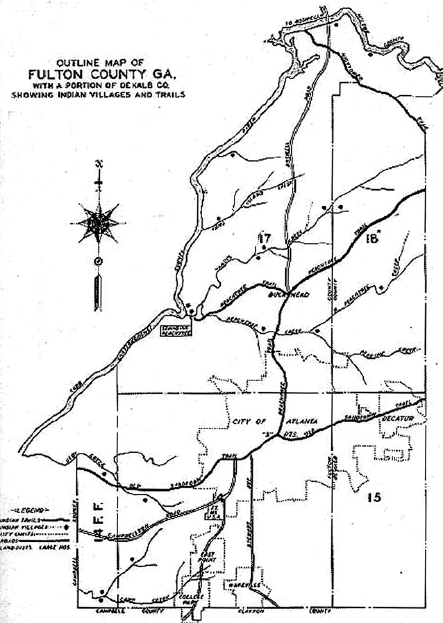

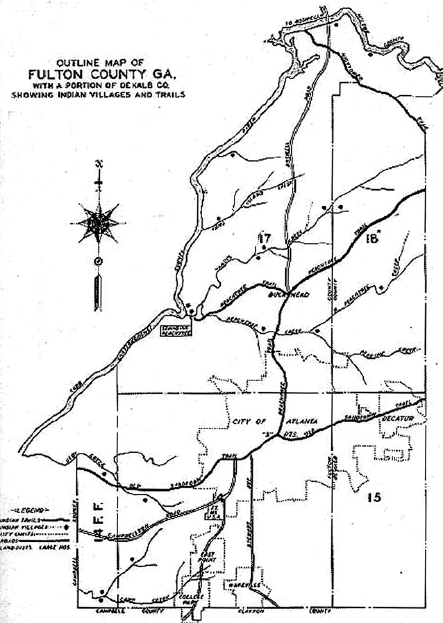

Roads and Native American trails, circa 1815, with late nineteenth-century Fulton County and city of Atlanta outlines overlaid.

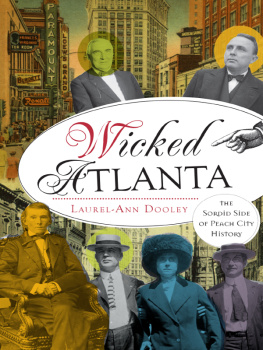

Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2009 by Corinna Underwood

All rights reserved

First published 2009

e-book edition 2012

ISBN 978.1.61423.341.1

print edition ISBN 978.1.59629.766.1

Library of Congress CIP data applied for.

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Dedicated to June Pearl Carson and the memory of Reginald Carson

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks go to Rachel Johnston for sharing her family knowledge of Martin and Susan DeFoor and Lance Haugan for his photographic expertise. Thanks also to Glen Martin, Robert Davis, Ken Denney, Professor Anne J. Bailey and Sue VerHoef for help with research.

INTRODUCTION

Atlanta is a dynamic city that has seen many changes over the past decades. Census reports indicate that the population stood at 4,917,717 in the twenty-eight-county Atlanta Metropolitan Statistical Area in 2006. According to statistics compiled by the U.S. Department of Justice, between 1976 and 2005, 53.7 percent of homicides occurred in large cities with a population of 100,000 or more. The FBI reports that the number of murders in Atlanta jumped by 22 percent in 2006, far surpassing the national murder increase of 1.8 percent.

Each chapter of this book covers specific cases of homicide, or suspected homicide, that took place in Atlanta dating from the 1840s to the 1990s. Interestingly, regardless of the era, many of the motives remain the same: hatred, prejudice and money. Early cases, such as the Atlanta Ripper murders and the murder of Mary Phagan, highlight racial tensions that were prominent in the South from the beginning of the twentieth century. Cases such as the Atlanta youth murders reveal how new developments in forensic technology, such as fiber analysis and DNA testing, have helped to provide evidence that was previously unavailable or inconclusive. While cases such as the Atlanta transgender murders indicate a need for stronger laws and more exhaustive police work, other cases, such as the disappearance of Mary Shotwell Little, remain unsolved in spite of the most thorough investigations.

There remain thousands of unsolved cases in and around the metropolitan area. Cold case squads are committed to reopening old murder cases, some going back thirty or forty years, to contact precious witnesses, locate new ones and recover new evidence. Their aim is to capture offenders who are still at large and bring peace and closure to victims families.

ATLANTAS FIRST HOMICIDES

The area of Georgia now familiar as the metropolitan city of Atlanta was once a Native American village called Standing Peachtree, inhabited by the Creek and the Cherokee. Back in 1825, the Creek nation ceded its land to the State of Georgia. The Cherokee continued to live side by side with their white neighbors until 1835, when, under the Treaty of New Echota, the Cherokee agreed to move west and Georgia took control of former Cherokee lands. This act ultimately resulted in the tragic Trail of Tears.

The Georgia General Assembly voted in favor of building the Western and Atlantic Railroad in 1836. A year later, work started on the eastern terminus, and the new settlement developed there was itself named Terminus. Within the next five years, the settlement had grown to thirty residents and six buildings, and the town was renamed Marthasville for ex-governor Wilson Lumpkins daughter Martha. Georgia Railroad chief engineer J. Edgar Thompson suggested the name Marthasville be replaced by Atlantica-Pacifica in 1845, and the name was shortened to Atlanta and made official the same year.

GEORGIA LYNCH LAW

Lynch law was a form of extrajudicial punishment meted out by vigilante mobs for presumed crimes. Lynching was popular throughout Georgia before and after the Civil War. Prior to the war, lynch mobs usually targeted anyone opposing slavery. After the war, white Georgians used lynching as a means of terrorizing free African American people who were voting. From 1868 to 1871, the Ku Klux Klan was responsible for more than four hundred lynchings involving African American men and women for supposed crimes against white people. Victims were often burned, hanged or sometimes beaten to death. The list of supposed crimes deserving of lynching ranged from raping a white woman to arguing with a white man.

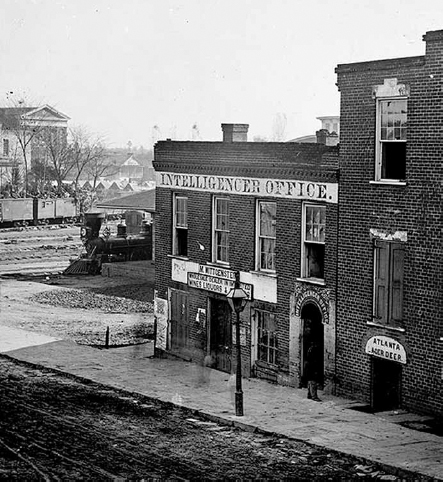

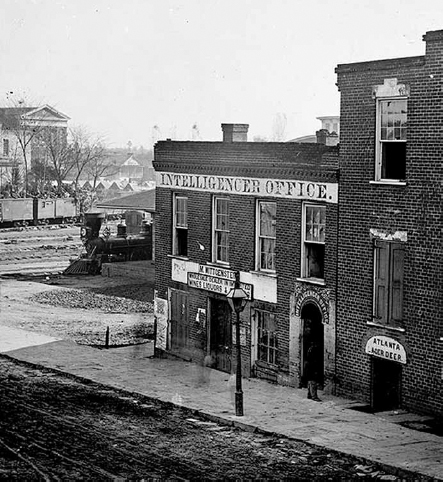

Atlanta Intelligencer office and railroad depot, 1864.

In 1881, the Atlanta Constitution expressed the shame and contempt that many of its readers felt about lynchings by expounding on the inadequacy of the legal system and demanding that lawmakers instigate a long-awaited change. In response, Georgia legislators attempted to suppress lynch law in 1897. Although the majority of representatives were against lynch law, few of them had a constructive strategy for stopping it. The New York Times reported that J.L. Boynton of Calhoun highlighted the complexity of the issue:

Lynching, in my opinion, is the result of combined causes. The practice has more or less prevailed in times of popular excitement, and especially in the new settled reasons before the establishment of the power of civil government. Criminal laws are imperfect, at best, and they are not administered with that vigor necessary to inspire confidence in their sufficiently. In criminal trials justice is often sidetracked and technicalities given the right of way. The people who do not understand such practice observe this, and losing faith in the adequacy of the law, take the law into their own hands.

Representative W.S. West of Lowndes firmly expressed his doubt in any resolution:

I do not think that the General Assembly can enact any law that would have any effect upon lynching. Sometimes there are crimes in the state that call for lynching, while at other times there is no excuse for it in the least. It is a difficult question to determine. I can only say stop the crime and you will stop the lynching.

J.W. Law, the only African American representative in the House, suggested a plan to control lynching: The only solution of the lynching question in Georgia that I can see is the education of the negro. Ignorance causes more crime in Georgia than any other thing. Educate the negro and you will prevent the crime of rape.

In 1893, the legislature passed a law that required law officials to summon a posse to quell mob violence. This meant that any sheriff failing to follow the new instruction could be charged with a misdemeanor and any citizens participating in the mob could be charged with felony or possibly murder. Some legislators, however, saw the shortcomings in the statute, the main one being that local law enforcers were unlikely to go to the extent of prosecuting mob participants.

Next page