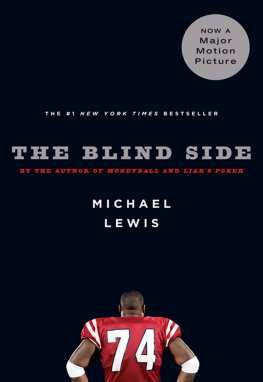

The Blind Side

The Blind Side

The Blind Side

CHAPTER NINE

The Blind Side

BIRTH OF A STAR

THE REDBRICK MONSTROSITY rises from a hollow beside a quiet road in the Buckhead section of Atlanta. To call it a home would be to give the wrong impression. Its less a shelter than a statement: the long sweeping driveway, the lawn that could double as a putting green, the giant white columns, the smooth stone porch inscribed with greetings in Latin. Through the leaded glass windows can be glimpsed sleek marble floors leading to a grand staircase lit by chandeliers with enough wattage to illuminate an opera house. Its the sort of place where the door really should be answered by an English butler, but Steve Wallace answers his own door. He wears shorts, T-shirt, and sandals, and has the pleasantly surprised air of a man who has just woken up from a dream that he is rich only to discover that hes actually rich. The only thing that the home and its owner have in common is that they are both huge. He walks across his great stone porch and onto his lawn to adjust the sprinkler. He limps; but they all limp. One nasty scar runs down his right knee and another lines his left ankle. Former NFL linemen age painfully and die young. No life insurance salesman in his right mind sells them coverage at the usual rates.

Hard as it is to believe nowas he returns to his mansion and passes through its stone halls toward the magnificent den with its elaborate audiovisual systemthere was a time when Steve Wallace worried about such financial trivia as life insurance. He worried about making a living. He wasnt born with money; all he knew how to do was block, and in 1986, when he started his NFL career, blockers didnt get paid much. His first contract guaranteed him $90,000 a year, which was pretty good, but he wasnt sure how long it would last. He sat on the bench, and waited, without knowing exactly what he was waiting for. It turned out he was waiting for Bubba Paris to eat himself out of a job.

After the 49ers won their first Super Bowl, in 1982, Bill Walsh had used his first draft choice to select Paris. Bubba was meant to be the final solution to Walshs biggest problem, the need to protect Joe Montanas blind side. At three hundred pounds or less, said Walsh, Bubba would have been a Hall of Fame left tackle. He was quick, active, bright, and he had a mean streak. Bubba also had a history of putting on weight, but, as Walsh said, we felt we could deal with that. And we did. Briefly. Walsh fined Bubba for being overweight. He inserted clauses in Bubbas contracts that paid him bonuses for showing up for work under 300 pounds. He sent Bubba to Santa Monica to live at the Pritikin Diet Center. He even hired a fitness instructor to drive over to Bubbas house every morning and feed him less than Bubba fed himself. Walsh did everything he could think of to keep Bubba from expanding. And then one day the fitness instructor showed up at Bubbas house and, as Walsh put it, The car was in the driveway, the drapes were closed, and nobody answered the door.

In his first four seasons Bubbas weight jumped around, but the trend line pointed up. Offered many choices between carrots and sticks, Bubba reached every time for another jelly doughnut. The 49ers won the Super Bowl again, after the 1984 season. But the next three seasons they went into the playoffs with high hopes and were bounced in the first round. In 1985 and 1986, they were beaten badly by the New York Giants, and in both games Lawrence Taylor wreaked havoc. Hed been too quick for Bubba. The 49er offense, usually so reliable, had scored only three points in each of those games. Joe Montana had been knocked out of the 1986 game with a concussion. The hits didnt always come from the blind side but the blind side was the sore spot. As 49er center Randy Cross said, Increasingly, we game-planned specifically for that rush guy on the right side. The right side of the defense, the left side of the offense, was the turf Bubba Paris was meant to secure. Theres that old Roberto Duran idea from boxing, said Cross. Get the head and the body dies. More and more teams were coming for our head.

It was at the end of the 1987 season that Bill Walshs frustrations with his promising left tackle peaked. That left side of the line was now, obviously, the pressure point that a very good pass rusher could use to shut down the 49er passing game. And Bubba Paris just kept getting fatter, and slower, and less able to keep up with the ever-faster pass rush. During the regular season Bubbas weight hadnt mattered very much. He was waddling onto the field at well over 300 pounds, and the 49ers still cruised through the season. Theyd finished with a record of 142. Amazingly, they had the number one offense and the number one defense in the NFL. Going into the playoffs, they were viewed as such an unstoppable force that the bookies had them as 14-point favorites to win the Super Bowl, no matter who they played.

They appeared to be a team without a weakness; but then, the regular season is not as effective as the playoffs at exposing a teams weakness. The stakes are lower, the opponents generally less able, their knowledge of your team less complete. Its when a team hits the playoffs that its weaknesses are most highly magnified; and in the 1987 playoffs, Walsh discovered that his seemingly perfect team had a flaw.

The first game was against the Minnesota Vikings, and it was supposed to be a cakewalk. But the Vikings had a sensational six five, 270-pound young pass rusher named Chris Doleman, and he came off the blind side like a bat out of hell. He was fast, he was strong, he was crafty, he was mean. He wore Lawrence Taylors number, 56, and when he was asked who in football he most admired, Doleman said, The one guy who has the desire to be the best, and the tenacity, is Lawrence Taylor. Im not saying I want to be exactly like Lawrence Every blind side rusher knew about the anxiety of influence. Doleman wasnt exactly Lawrence Taylor but he was exactly in the tradition of Lawrence Taylor. Hed been drafted as an outside linebacker, but in the 43 defense, which the Vikings played, the outside linebacker wasnt chiefly a pass rusher. Finally it occurred to the Vikings coaches to try him as a right defensive endthat is, to make him a pass rusher. To give him the role in the 43 that Taylor played in the 34. He was an instant success.

Fearing that Doleman might shut down his passing game, Bill Walsh considered his trick of pulling a guard to deal with him. John Ayers had moved on, and the 49ers had no one quite so well designed to the job. Anyway, the trick was old: the Vikings would see it for what it was and quickly move to exploit the hole left in the middle of the 49er line. They had a weapon to serve just this purpose: right tackle Keith Millard. He lined up beside Doleman, and was himselfoddly, for a tacklea speedy pass rusher. Send the guard to help with Doleman and you left Millard to run free. Walsh couldnt do that.

Thus Bill Walsh received another lesson about the cost of not having a left tackle capable of protecting his quarterbacks blind side. This time the lesson was far more painful than the last. This time he had expected to win the Super Bowl. He had built the niftiest little passing machine in the history of the NFL, manned with talented players, and this one guy on the other team had his finger on the switch that shut it down. Chris Doleman hit Joe Montana early and often, but even when he didnt hit Montana he came so close that Montana couldnt step into his throws. Backup left tackle Steve Wallace watched from the sidelines. He never let Joe get his feet set, he said later. What Doleman did to Joe Montanas feet was minor compared to what he did to his mind. Every time Joe went back, he was peeping out of the corner of his eye first, said Wallace, then looking at his receivers. The pass rush rendered Joe Montana so inept that in the second half Walsh benched him and inserted his backup, Steve Young. Young was left-handed, which enabled him to see Doleman coming. Young was also fast enough to fleewhich he did, often. Against a team they were meant to beat by three touchdowns on their way to an inevitable Super Bowl victory, the 49ers lost 3624. Afterwards, Vikings coach Jerry Burns told reporters that the way to stop [the 49ers] is to pressure the quarterback. Our whole approach was to pressure Montana.