Table of Contents

To Matthew, Dominic, Joshua, Tamsin, Ivo, and Luca

INTRODUCTION

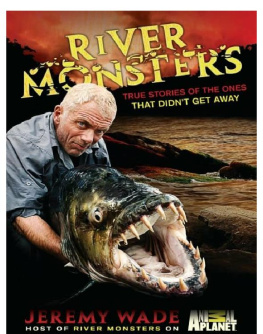

WHY SOME FISHERMENS TALES ARE TRUE

But I will lay aside my Discourse of Rivers, and tell you some things of the Monsters, or Fish, call them what you will, that they breed and feed in them....

Izaak Walton,The Compleat Angler,1653

ITS A DISTURBING EXPERIENCEseeing something that doesnt exist.

In July 1993 I was floating in a leaky wooden canoe on a muddy Amazon lake, known simply as Lago Grande (big lake), looking for arapaima. Unusually for fish, Arapaima gigas are air-breathers. Despite having gills, they have to surface at half-hour intervals to burp stale air from their swim bladder and gulp a fresh mouthful down. Its a quirk that allows these super-predators to stay active in stagnant water, when other fish are going belly-up. And without doubt its one of the reasons they grow so huge. Just how huge is not known for sure, but they are commonly said to be the biggest freshwater fish in the world, with some supposedly reliable sources quoting a maximum length of fifteen feet. So they shouldnt be too hard to spot, particularly as theyre also not exactly camouflaged, being decorated all over with vivid red markings. So why hadnt I seen a single one?

Perhaps they had all been harpooned or nettedthe one drawback to being so large and visible. But local fishermen assured me there were still arapaima in the lake, mainly because theres a very deep hole, over seventy-five feet deep, off the southern end of the central island where their encircling nets cant reach the bottom. A few days before, Jos had even pointed some out to me:

There! The size of this canoe! ...

But the distant ripples looked no different from any of the others that he had pointed out earlier, made by river turtles, caimans at periscope depth, and other fish. Or so he said. As far as I was concerned, he was seeing things that were invisible. I recalled how other fishermen had told me that the lake was encantadoenchantedhow an invisible force sometimes held canoes out in the middle, and how the fishermen had strange dreams when they camped here, dreams about ghost ships from an underwater kingdom whose occupants silently beckoned. No wonder fishermen have such a reputation for invention and exaggeration and for being all-around unreliable witnesses. Perhaps the arapaima wasnt a real fish at all but rather a spirit living in another dimension, a spirit you can only see once youve lost your grip on reality after too much time staring at the water.

Or maybe I needed to look harder. Back home, beside an English pond I could locate a feeding carp from the tiniest whorl on the surface, spun by its tail as it rooted head-down in the silt. But this water spoke a different language that I couldnt yet decipher. Where Jos saw a clear signature I saw a meaningless scribble.

But foreign languages can be learned. In time I started to recognize the subtly different ripple patterns. My eyes began to enhance detail and eliminate noise, to sharpen edges and slow down time, so that I too could tell not just the species but also the size and direction of traveleven, sometimes, whether or not the ripple-maker knew it was being watched. But back then, my first time in the Amazon, it felt as if the lakes inhabitants were mocking me. Dejected, I stared at the water and pondered the strange mechanics of perceptionthe perplexing fact that you can only see something properly if you already know what youre looking for.

Such was my state of mind when, thirty yards from the boat, the surface opened and something huge heaved into the air. The size was right for a very big arapaima, but the shape was all wrong. What Id seenif the blurred afterimage wasnt deceiving mewas an arched back, bright pink in color and bearing a row of large triangular points. It was like some huge gear wheel in the lakes workings, briefly cutting into the air before spinning back into the depths.

What it was not like was any living creature in the real world.

Back at the hut that night I described it to Jos, who knew the lake better than anyone. He regarded me over his ragged moustache and then asked where I was keeping my secret bottle of cachaaand why I wasnt sharing it with him.

Nothing like that lives here, he said.

All the other fishermen I told about it said the same thing.

So what do you do with an experience like that? Do you keep talking about it in the face of disbelief or even ridicule? Or, like a puzzled spectator at a magic show, do you admit that your eyes must have been trickedor, rather, your brain has misinterpreted the signals from your eyes? For the sake of my sanity, I allowed the outlandish visionwhich had once screamed for attentionto fade from my memory.

And thats how things would have stayed if I hadnt gone back the next year. I was still looking for arapaima, but I also cast lures into the lake margins for smaller speciestucunar (more widely known as peacock bass), surubim, and aruanusually to return to the water but sometimes for the pot. On one particular day, when these fish were proving more elusive than usual, there were several pink river dolphins breaching in the area of the deep hole. These (the scientific name is Inia geoffrensis, but they are known locally as botos) are among the Amazons strangest looking animalshump-backed with a bulging head that contains an echo-location organ and sports a narrow, toothy beak. I decided to pack up fishing for the day and try to photograph dolphins instead.

With my 135mm medium-telephoto lens, I had to be pointing right at them to get them in the frame. But they appeared through the surface without warning, in random positions, for just a fraction of a second ... and by the time Id reacted they were gone. However, with the bright sunlight and fast film, I could set both a fast shutter speed, to freeze the action, and a small enough aperture to give a good depth of field so I didnt have to fiddle with fine focus. I then waited with the camera raised, ready to react to the loud exhaling puff that signaled a breach.

The next couple of hours saw me almost dislocate my neck several times, as I snapped round and pushed the shutter, as well as nearly tipping myself out of the boat, which was wobbly enough even when I was keeping still. I had an idea that Id clicked on a dolphin or two, but there was no way to know until I had the slides processed.

Several weeks later, when I got back to the UK, most of the frames were much as I expectedshots of the sky and skewed horizons, some with anonymous splashes or spreading ringsbut I did have a couple showing a dolphins humped back.

Then I held another slide up to the lightand there it was: the shape that had been transient and blurred on my retina, now clear and sharp on film. But what on earth was it? The picture was published in BBC Wildlife magazine, sparking speculation that it might even be an unknown new species. I returned to the lake the next year with a video camera provided by the BBC Natural History Unit, and after a sixweek stakeout I captured it on videotape in just three grainy framesbut unmistakable.