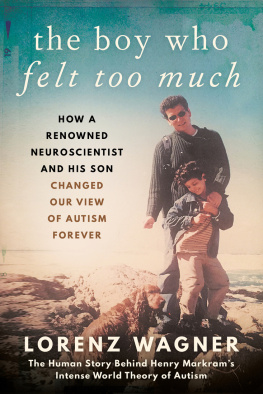

International praise for

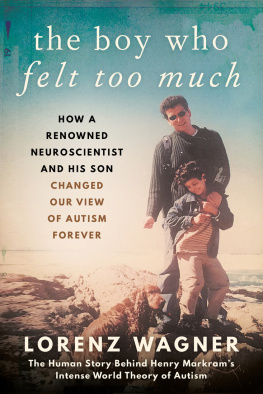

The Boy Who Felt Too Much

Lorenz Wagners book on the remarkable Markrams is, well, remarkable. This is an extraordinary story of noted neuroscientists seeing the world though the eyes of their ASD son and then helping change the way autism is seen and treated far and wide. A tale of love, constancy, and groundbreaking research. RON SUSKIND, Pulitzer Prizewinning journalist and author of Life, Animated: A Story of Sidekicks, Heroes, and Autism

A compelling story about one of the worlds most brilliant researchers searching to understand his sons autism. A gloriously positive book. Left me with hope for humanity. DAVID SINCLAIR, professor in the Department of Genetics and codirector of the Paul F. Glenn Center for the Biology of Aging, Harvard Medical School

The Boy Who Felt Too Much tells the story of our accelerating understanding of autism, and it does so via fascinating characters, such as the famous neuroscientist Henry Markram, who is building a digital brain, and Dr. Markrams remarkable autistic son, Kai. It offers a very enjoyable way for anyone to become fluent in the latest theories about autism, including why it seems so prevalent today and what can be done to minimize its most troublesome aspects. This book greatly increased my respect for the condition of autism, as well as the individuals and families who navigate life with it. MARTINE ROTHBLATT, chief executive officer, United Therapeutics Corp

A moving father-son story interspersed with elegant science writing about regions of the human brain that are still terra incognita. Thoroughly researched and brilliantly written. WESER KURIER

A book for all those dealing with autism and those who love good writing. SDDEUTSCHE ZEITUNG

A wonderful book. ANJA BURRI, NEUE ZRCHER ZEITUNG

First published in Australia and New Zealand by Allen & Unwin in 2019. First published in the United States as an English-language translation in 2019 by Arcade Publishing, and imprint of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

Copyright Lorenz Wagner 2018

English-language translation copyright 2019 by Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

Originally published as Der Junge, der zu viel fhlte in 2018 by Europa Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Berlin

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone:(61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web:www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76052 943 7

eISBN 978 1 76087 294 6

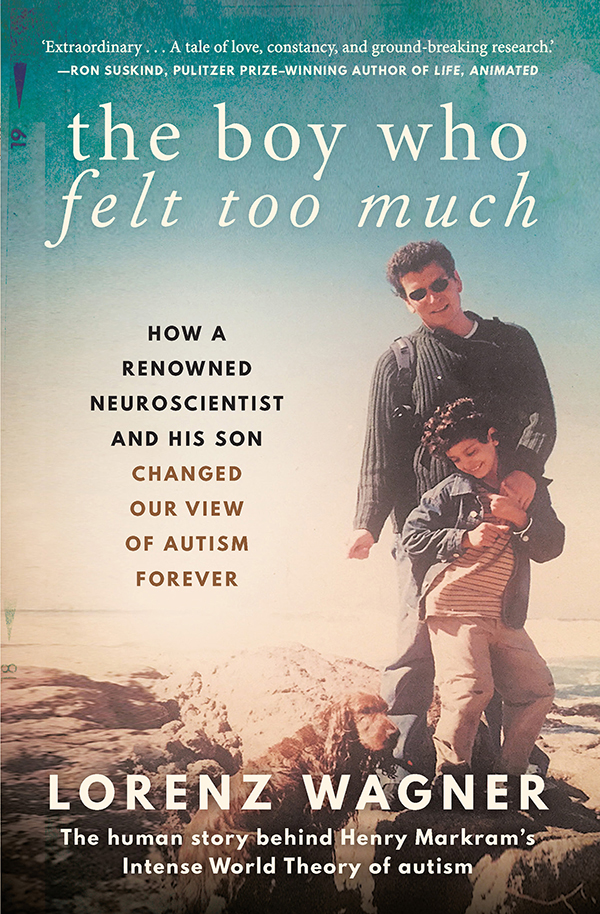

Cover design by Erin Seaward-Hiatt

Cover photograph courtesy of the Markram family

For Romy

Contents

Is that your son?

Yeah, why?

You wont believe what he just did.

The car was coasting. Kai heard the wheels crunch as it drew to a halt outside his house. The car door opened, and a young man hopped out. He popped the hood and disappeared beneath it. Youve got to be kidding me! he fumed.

Kai emerged from the front yard. It was late in the morning, and the street was empty. Cars were a rare sight around there. Kai often played in the street with his sisters. Mostly only bikes passed by, anywaystudents on their way to class. Kai lived with his parents and sisters on a sprawling college campus, which boasted sculptures, water fountains, benches, flame trees, a Japanese garden, and enough space to spend the whole day wandering idly, accompanied by chirping birds.

Hello. Im Kai.

The man ignored him.

Is your car not working?

No, the man grumbled. How would he get to class now? He was stuck in this damn residential area and would be too late for his exam. If he didnt make it there on time, theyd mark him absent and fail him.

Kai spun around and dashed off. The man got back in his car and turned the key. The engine sputtered for a moment and died again.

The boy came running back. What the hell did he want?

He was holding something in his hand.

Here, said Kai. My moms key.

Excuse me?

You can take our car.

The man stared in disbelief and took the key.

* * *

Kai loved people, and it was hard not to love him back. At the age of two, he started twisting his way out of his fathers grip and running over to themrandom pedestrians, the postman, elderly people sitting on benches basking in the warmth of the morning sun. Kai opened his arms and clung to their legs. He didnt say anything. They froze at first, but when they looked down to see his twinkling brown eyes staring up at them, they couldnt help but laugh. Kai didnt speak much. He spoke with his hands and glowed from inside. He warmed their hearts more than the sun possibly could. Soon they were sitting on the benches because of him, the little boy who had just moved to Rehovot, Israel.

Kai was born in Heidelberg, Germany, on June 21, 1994, the first day of summer. It was the longest day of the year and proved to be the longest birth his mother Anat would have to endure, dragging on some twenty hours. While she twisted and turned in pain, Henry wandered up and down the hallway. Their two daughters, Kali and Linoy, would soon have a baby brother. They could barely contain their excitement.

The midwife laughed when she held Kai up by his feet. He was so long and heavy and had so much hair on his head. We might as well put a jacket and pants on him, she said. Send him straight to kindergarten.

* * *

Babies are often born with a smile on their face. Experts call this a reflex smile. Its a newborns way of ingratiating itself. That smile is many parents first memory of their child. Henry doesnt remember if Kai was smiling. He remembers something else: newborn Kai kept trying to lift his little head. His wide eyes had this absorbing glimmer, tracking every light and sound, darting back and forth on high alert.

Henry had treated many babies during his time at medical school, but he had never seen eyes like that. His sons gaze seemed targeted, intentional. That was impossible. A newborns vision doesnt develop for another few months. Until then, everything is blurry to their eyescolors, contours. They can only see whats right in front of them: their parents faces, the mothers breast. Kai, however, behaved as though he could see.

His pupils darted nonstop. Henry was worried. The doctors on the ward huddled. They had never seen a child like that either. As they inspected Kai carefully, the worries vanished from their faces. Kai scored a full ten points on the Apgar test, which rates a newborn by appearance, pulse, grimace, activity, and respiration. All good, boss, his colleagues told him. Henrys fears turned to pride: He is the most alert child on the ward, he told Anat. Our son is something special.

Anat wasnt all that comforted. She watched Kai even more closely. When he was around six months old, she noticed a change in his eyes. She couldnt put it into words; it was a feeling more than anything. Henry didnt see it. Neither did the doctor they consulted. A wonderful child, he assured them, fit as a fiddle.