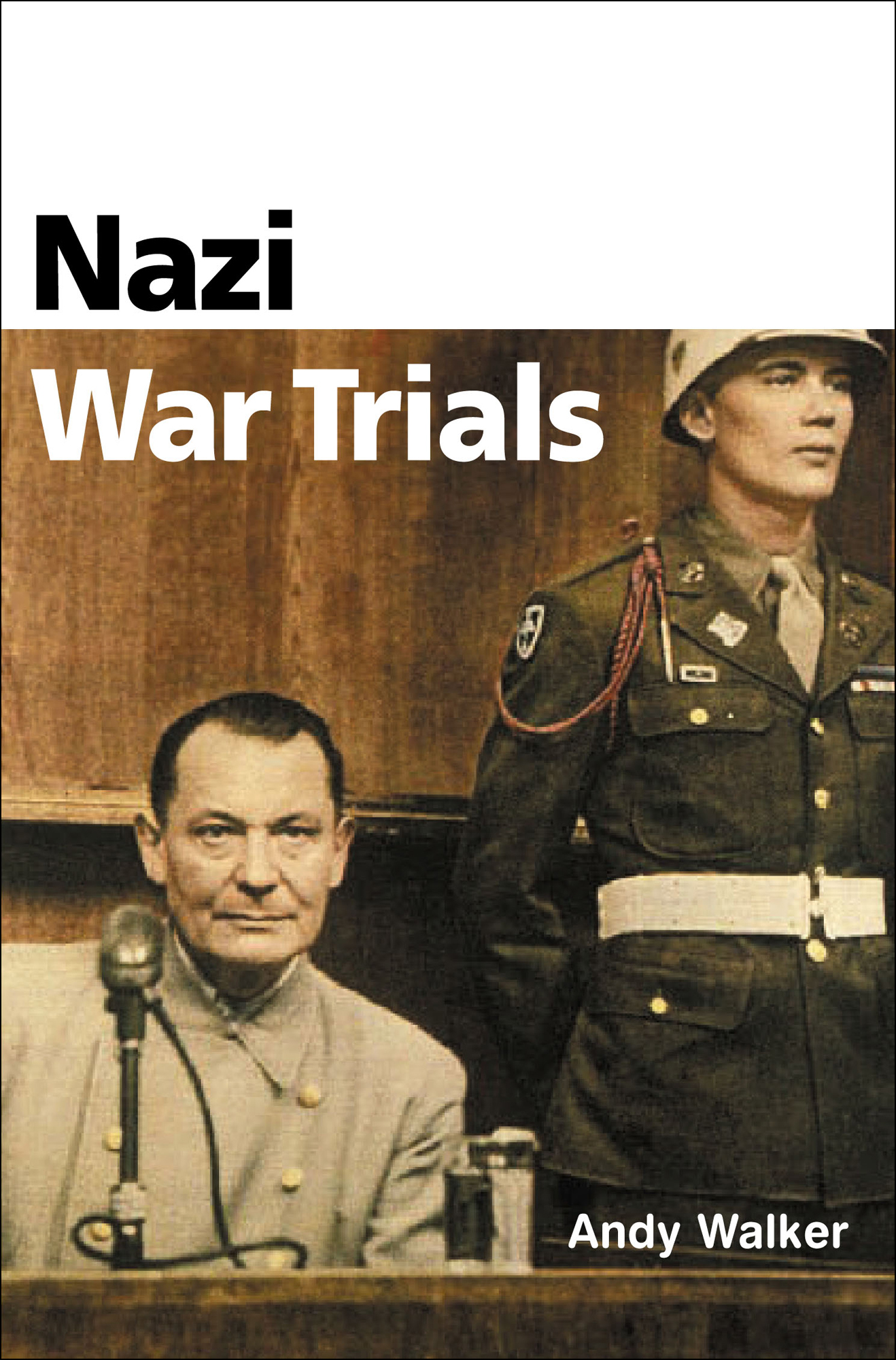

At the end of the Second World War the victorious Allies began unprecedented proceedings against those leading Nazis who had survived and been captured. They charged them with crimes against humanity and put them on trial. This Pocket Essential looks at the Nuremberg Trials and at the personalities involved from defendants like Herman Goering and Rudolf Hess to the judges and the prosecuting and defending counsels. It provides a chronology of the proceedings in the court-room and refers frequently to the terrible events Nazi rule had unleashed on Europe for which the defendants found themselves in the dock. The fates of the major players in the drama at Nuremberg are all revealed. And the book asks the questions that were raised at the time and have not been fully answered since. What was the legal validity of the trials and were the ones who were tried always the right people to bear the responsibility for Nazi crimes?

Andrew Walker has long had an interest in the trials that followed World War II and is a regular reviewer for Waterstones Books Quarterly - but these two points are in no way related.

The Nazi War Trials

ANDREW WALKER

POCKET ESSENTIALS

In memory of

Betty Aileen Roberts

1916 2003

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for the kindness and support shown by SarahWalsh and Nick Rennison during the writing of this book.

Contents

Background to the Trial; The Defendants; Preparations for the Trial

The Trial Begins; The American and British Cases; The French Case; The Soviet Case

Gring; Hess; Von Ribbentrop; Keitel; Kaltenbrunner;Rosenberg; Frank and Frick; Streicher; Schacht and Funk; Dnitz and Raeder; VonSchirach; Sauckel; Jodl; Seyss-Inquart; Von Papen; Speer; Von Neurath andFritzsche; Bormann

Closing Speeches;Deliberations; The Verdicts on Individuals; Sentencing; Carrying Out theSentences

Introduction

One of the most extraordinary things about the Nazi War trialsin Nuremberg in 1945 and 1946 was the fact that they took place at all. At theend of the most devastating war in history, victors as well as vanquished wereexhausted. Much of Europe was in ruins. Germany itself was a virtual wastelandand many of its people were close to starvation. In this context, the fact thata tribunal was convened and that, over a period of more than a year, thoseleading Nazis who had survived and been captured were tried for war crimes andcrimes against humanity is astonishing enough.Yet, the trials themselves wereunprecedented. Never before had nations in victory attempted to hold theleaders of the defeated nation to legal account. The challenges faced by thosewho established the tribunal were enormous. The international law under whichthe men were tried was debatable. The argument that the trial was vengeancemasquerading as justice was one that was heard from its beginning. To prove,as Rebecca West wrote, that victors can so rise above the ordinarylimitations of human nature as to be able to try fairly the foes theyvanquished, by submitting themselves to the restraints of law would be no easytask.

From the very beginning the NurembergTrial was about much more than the individual fates of the men who stood trial.It became the focus of desires for a post-war settlement in Europe that wouldensure lasting peace and that would exorcise the horrors of the previous sixyears. It embodied hopes that solutions could be found to problems ofinternational con fl ict whichhad plagued the continent for centuries. Again in the words of Rebecca West, itcould warn all future war-mongers that law can at last pursue them into peaceand thus give humanity a new defence against them. In this sense, the Nazi WarTrials can be seen as one of the most signi fi cant events of the twentieth century.

This book is primarily an attempt toprovide a clear and accurate prcis of what happened at Nuremberg between 20November 1945, when the trial began, and 16 October 1946, when sentence wascarried out on those men convicted by the tribunal. It identi fi es each of the defendants, summarisesthe charges against each of them and gives a brief account of the prosecutionand defence speeches, the judgement, the sentencing and the carrying out of thesentences. It also looks at the cases the Allies made against various keyorganisations within the Nazi state.To set the trials in context, the bookexamines the debate amongst the Allies before the war ended about what formjudgement on the Nazis would take and looks brie fl y at events after they were concluded.At a time when the war crimes court in The Hague still pursues men involved inthe Balkans War and when the trial of Saddam Hussein in Iraq is underway, theNuremberg Trial has a renewed relevance and this book endeavours to show why.

Preliminaries

The wrongs which we seek to condemn andpunish have been so calculated, so malignant, and so devastating, thatcivilization cannot tolerate their being ignored, because it cannot survivetheir being repeated.That four great nations, fl ushed with victory and stung with injurystay the hand of vengeance and voluntarily submit their captive enemies to thejudgment of the law is one of the most signi fi cant tributes that Power has ever paid to Reason.Robert H Jackson, Opening Address for the United States, November 21 st 1945

Background to the Trial

As the Allies began their advance upon Germany on two fronts in1944, the fate of the top ranking Nazi leaders was being hotly debated. The oneabiding aim for all parties was to avoid the travesty of justice that hadfollowed Germanys surrender in 1918. Then the German government had beencharged with the prosecution of those men accused of war crimes. After thepunitive Treaty of Versailles, the will to pander to the demands of the Allieswas clearly lacking, and the Kaiser was able to live out his days in peaceableexile in the Netherlands. Other cases were pursued with no more vigour: out ofthe 45 cases set for trial, only 12 came to court, and from them only six menwere convicted.

In 1944 then, the Allies had a precedentto avoid, but little more of substance. As early as October 1941 Churchill andRoosevelt had declared that the punishment of crimes committed by the Nazis wasa major goal of the war. In 1943 three German of fi cers were found guilty by the Sovietsand shot. After D-Day, American and British troops were increasingly likely toapprehend such people and a uni fi ed protocol was urgently required. By Churchills own account,the issue had been encapsulated in a bizarre exchange between the three leadersat Teheran in 1943. Stalin stated his opinion that justice would be served bythe execution of 50,000 Nazis. Churchill remonstrated that he would sooner betaken out into the garden himself and shot than countenance such an idea.Roosevelt, mediating between his two fellow leaders, came up with the somewhatghoulish compromise that 49,000 should suf fi ce. Churchill stormed out of the room, only to returnwhen Stalin assured him that the remark was made in jest. Thus Churchillpainted a scene of the British sense of justice outraged by Soviet barbarity,with only the pragmatism of the Americans to unite them.

Yet the reality was not quite soconvenient. It was Churchill who was set on the idea of summary justice, fearingthat a long drawn out trial would provide an unwelcome opportunity for the Nazileadership to garner sympathy. In notes made by the deputy cabinet secretary(made public only in 2006), its clear Churchill proposed execution for Hitler,Instrument electric chair, for gangsters, no doubt available on lease-lend.He also proposed that a list of grand criminals be drawn up, and these menbe shot as soon as they were caught and their identity established. Asurprising stickler for propriety was Stalin, who, not known to be troubled bythe concept of a trial taking any longer than he wished, counselled against theabsence of a court hearing and warned that this would leave the Allies open toaccusations of vindictiveness. The British Ambassador in Moscow caught theSoviet attitude perfectly when he demurred to Stalin,I am sure that thepolitical decision that Mr Churchill has in mind will be accompanied by all thenecessary formalities.